Media commentator, James O’Brien, is becoming my go-to guy when it comes to hitting the nail on the head, problem-finding-wise. Here’s how a recent New Statesman article of his begins:

“I’m joined now by Galileo Galilei, a follower of Copernicus who has used modern telescope technology to make astronomical observations that he believes prove heliocentrism beyond any reasonable doubt. “Also joining us is Nigello Lawsini, who has no scientific training whatsoever but has written a short book insisting furiously that the sun does in fact revolve around the Earth. Because he says so. “As the presenter of this programme, I shall now offer exactly equal amounts of time to each guest and treat their conflicting positions as if they are of equal intellectual and epistemological value.”

As I’m reading the article, I’m reminded of the quote attributed to journalism professor Jonathan Foster: “If someone says it’s raining and another person says it’s dry, it’s not your job to quote them both. Your job is to look out the f**king window and find out which is true.”

Part of the problem here is that the cost of writing and publishing a book, especially an ebook, is rapidly tending towards zero. Therefore, anyone can create a book. About anything. Viva freedom of speech. The ‘thud of credibility’. The media, unfortunately, still thinks that an author with peculiar views and a book describing them makes for a ‘balanced’ argument against someone who actually understands their subject, has rigorously studied it and subjected themselves to years of peer review.

The situation is not helped by the shear amount of media that’s out there. The cost of assembling a podcast, ezine, blogsite, etc, etc also tends to zero. What counts in this kind of environment, therefore, is Share Of Mind. Facebook and Twitter are the masters of capturing it. They know – or rather their algorithms have worked out – that people love arguments, they love (self-)righteous anger and they love whoever tells the best story. The media knows, too, that to fight the dominance of Twit-Face, they also need to play the game.

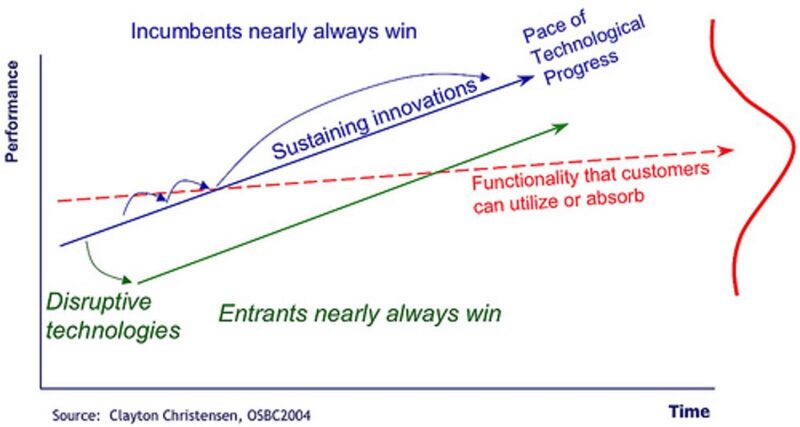

The big problem though is that 99 times out of a hundred, the person that tells the stickiest story is the cretinous charlatan. It works something like this: If truth is on your side, you fool yourself into thinking that will be enough to win the day, so you devote the bulk of your time to finding more truths. Conversely, if the truth is not on your side, your only way to win an argument is to find better ways to tell your story. Which means you learn how to focus on cunning aphorisms, wild examples and, best of all, incredible stories that make listeners wish they were true. Stories that listeners want to then share with other listeners. All the while leaving the person that’s gone to the trouble of finding the truth sat alone at the end of the bar. Billy-No-Mates. Introvert book-worm versus ribbons-and-bows, loud-mouthed raconteur.

And thus the media unwittingly – or is it? – causes the spiral of lies and dysfunction to spin out of control. The best story wins the most likes.

In theory, the answer to this vicious cycle is for Billy-No-Mates go on a few intensive story-telling workshops. But then you end up with Brian Cox. Which definitely doesn’t help either.

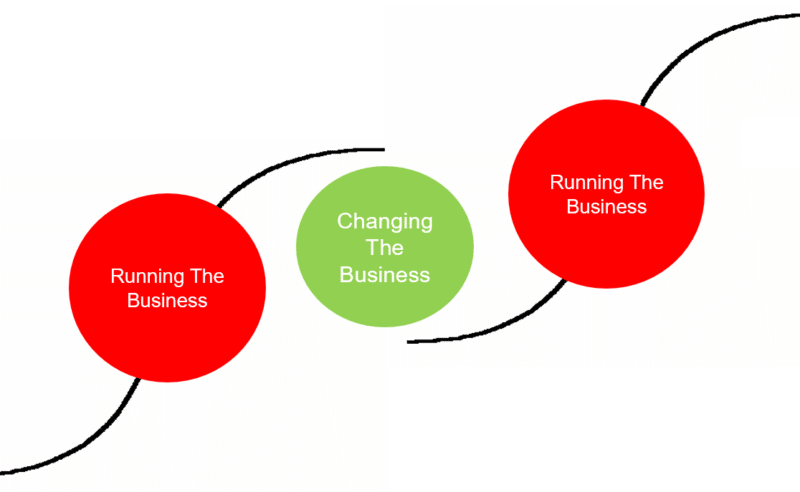

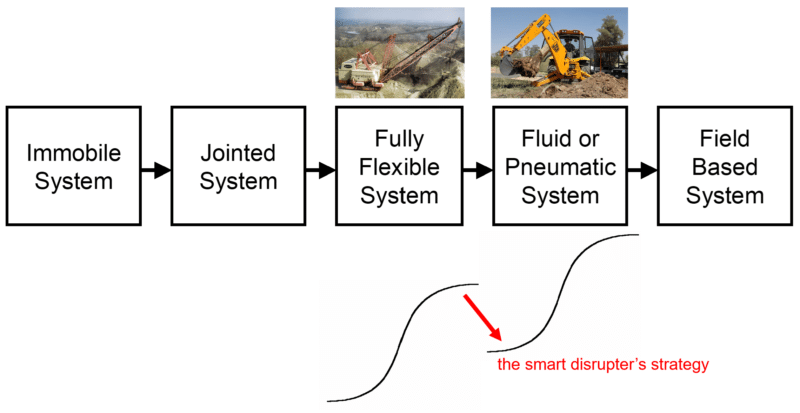

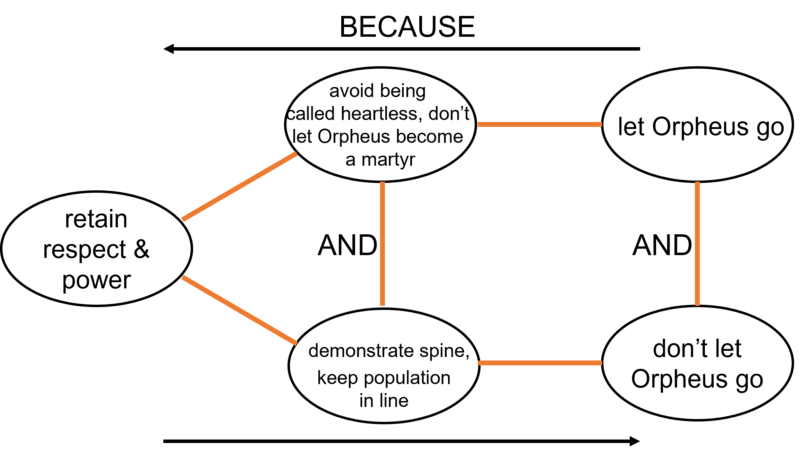

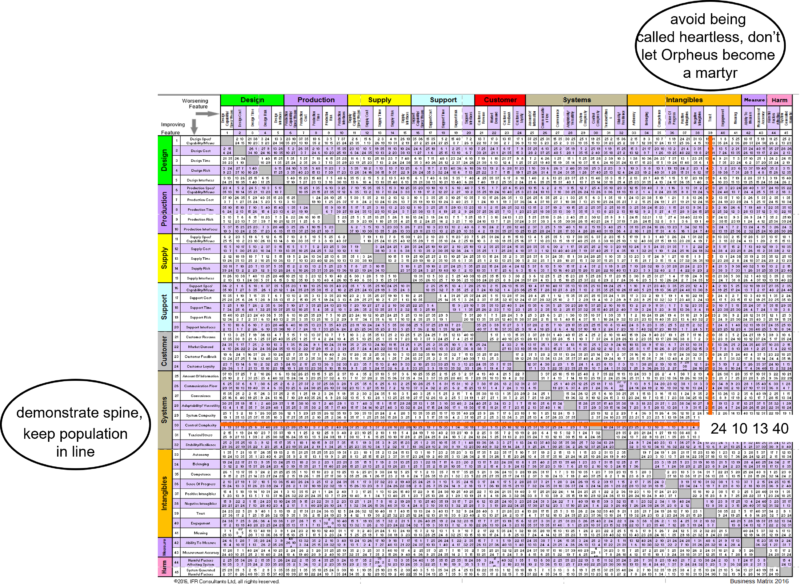

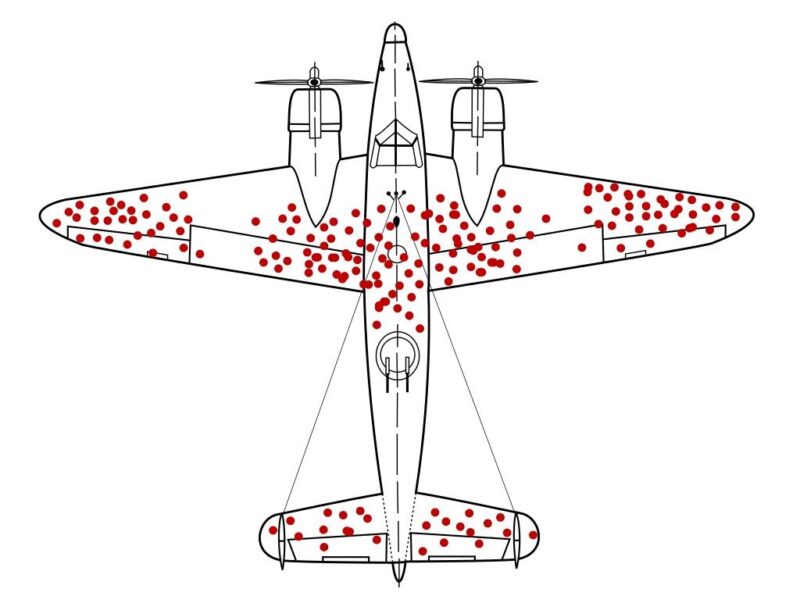

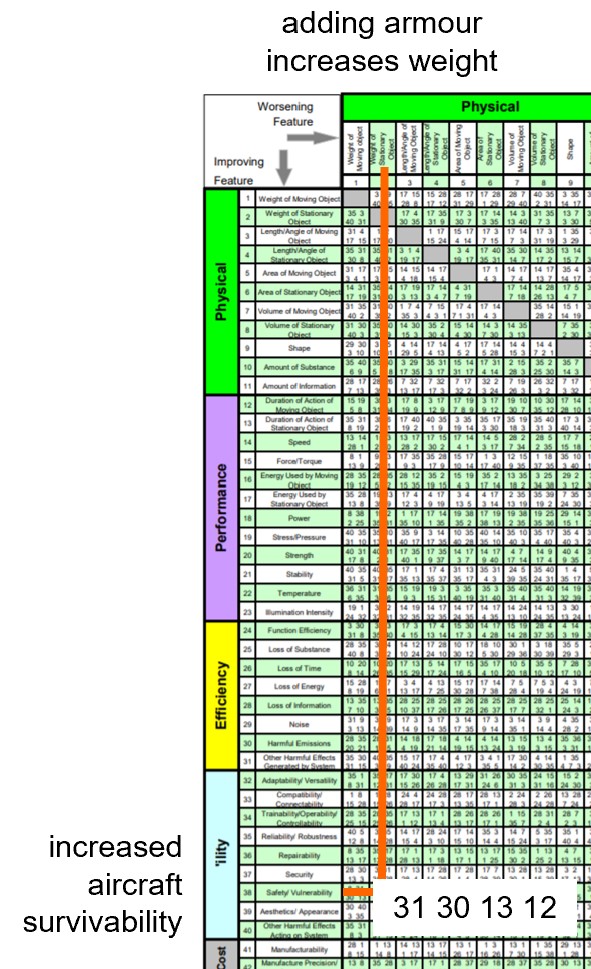

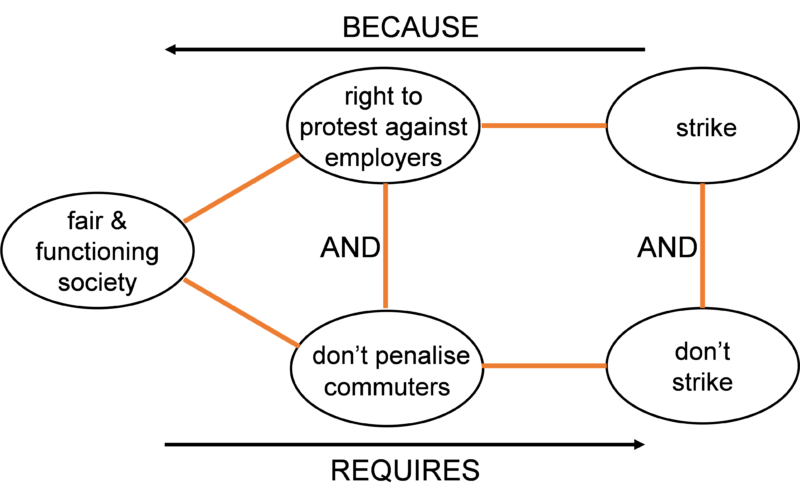

The problem is deeper than that. It’s the one first described by Edward De Bono in his critiquing of what he labelled ‘The Gang Of Three’, and in particular, the Gang’s leader, Socrates. Socratic thinking is the world’s dominant thinking method. It’s what still gets taught at Journalism School. Get two opposing views together and have them slug it out until logic wins the day. It’s better than nothing. But it’s no longer good enough for the complex world we now all inhabit. Socratic thinking is either/or thinking. This was sort of okay when the world was simpler and didn’t change very fast. But now everything is connected to everything else, either/or thinking just means we all end up going around in circles, passing the trade-offs from one person to the next, with – as we now know – the person with the least interesting story ending up with the resulting shit on their lap.

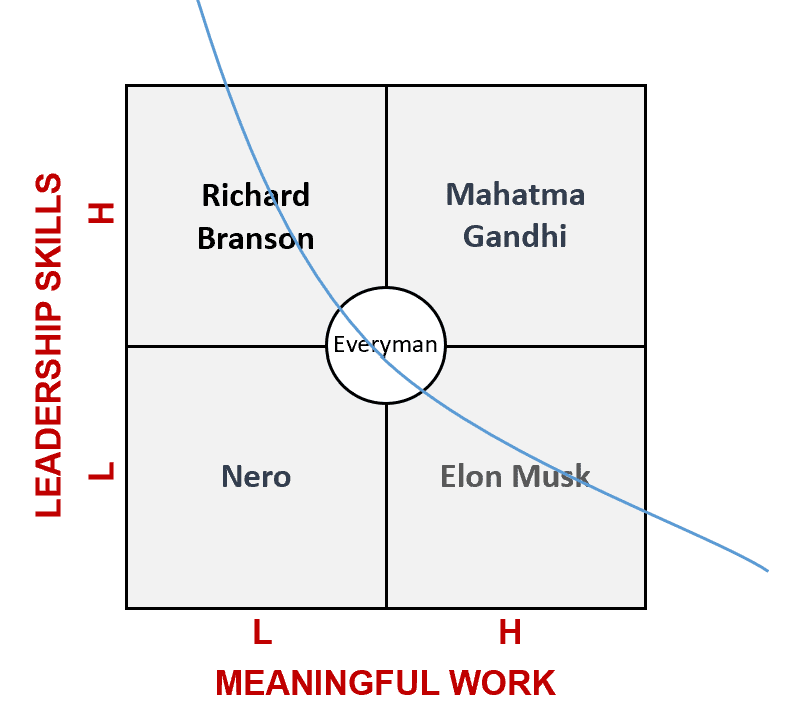

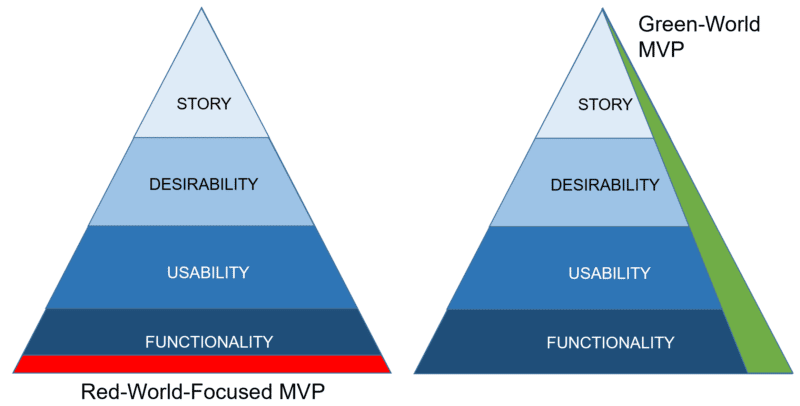

The Jonathan Foster solution to this excess-Socrates problem is that the journalist is the one tasked with helping everyman to determine the truth. If their thinking is also Socratic in nature, though, the best they can hope for is to act as some kind of a referee. A referee that gets to look at the either/or spectrum and decide which is the best compromise point between the two extreme views. Except the ‘right’ answer – if there is such a thing – is never on that spectrum. It lies in a third dimension. The one introduced by Hegel. Thesis-antithesis-synthesis. The Third Way. A third person in the discussion. Fourth if the journalist doesn’t have the skills to look out the window and see ways forward that resolve the conflict between Bill-No-Mates and the loud-mouthed raconteur and generates a higher level solution. A solution that might reveal one or both of the thesis-antithesis opponents are talking bollocks. And a preceding discussion that, by putting conflict at its heart, could also help satisfy the media urge for share-of-mind generating thrills and spills.

Or maybe. There’s still the problem of people not liking smart-arses. And it would be very easy for the synthesis-focused Third Way spokesperson to find themselves trapped in that smart-arse position. Who made them the decider?

Every problem is solvable, of course, and, if we believe our own methods, someone, somewhere will already have found the solution for us. Or at least the basic foundations of a solution.

Which is what I think we can see in, of all places, the Welsh Government. An organisation that has in effect created a Third Way oriented person in the form of a Future Generations Commissioner. A person tasked – per the Well-being Of Future Generations Act of 2015 – with representing future generations during the usual Socratic either-or policy debates.

The fact that the role has existed since 2015 and is still there is probably some kind of testament that the idea works (especially when pitched in terms of a Commissioner that is in effect tasked with representing the future of our children). The fact that most people haven’t heard about it, or sought to replicate it elsewhere is that, when I read the Act, it doesn’t have enough teeth, and – more importantly – they haven’t done a good job of telling their story. And especially the idea of seeking to switch nugatory either/or choices into both/and breakthroughs. Which is a pity since, I think, the story is an almost unbeatable Hero’s Journey tale if it can be told right. Which is where things come full circle back to the media again. A shiny new Third-Way Media.