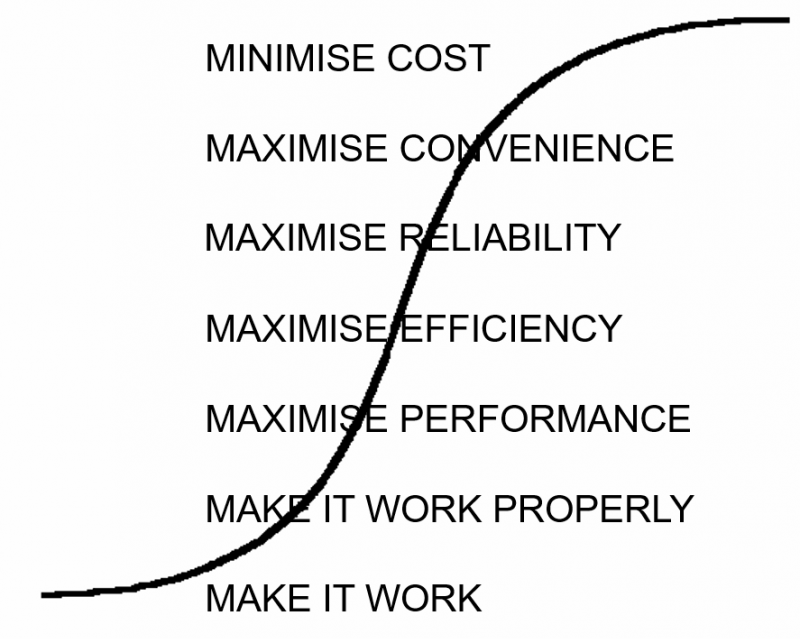

There aren’t many universals in life, but the S-curve offers us one of them. S-Curves are everywhere and apply to systems of every kind. When viewed from a business, industry or societal perspective, the S-curve features a number of, again universal stages:

After having the first flickers of an idea for a new way of doing things, the first job is to somehow make it work. Then the job becomes making it work properly. Then maximise performance. Then efficiency. Then reliability. Then convenience. Then, when there’s nothing left to improve, the final job becomes one of minimising cost.

Thanks to the Japan-triggered quality revolution of the 1970s, most industries have become extremely good at accelerating this sequence of events. To the point, now, where almost every domain on the planet finds itself at the top of its current s-curve.

Perhaps the most iconic examples of this can be seen in the automotive industry. Thanks to the Model T Ford, the automobile is quite literally, to steal the title of the book that sparked the Lean movement, ‘the machine that changed the world’. That this happened, is, overall, an amazing achievement. By the end of the 1990s, however, when we started working with several automotive OEMs on ‘5-day’ car projects, the industry was already at the tail-end of the ‘maximise convenience’ stage. The big idea underpinning these projects involved refining logistics operations to the point where a customer could go into a car dealership, choose their car, choose all of the different options – colour, trim, engine size, air-con, carpets, tinted-windows, sound-system, etc – and then have it delivered to them five days later. The OEMs quickly found themselves in a race. If they can do a 5-day car, we need to be able to offer 4. And then 3. Until, finally, someone asked the question, ‘does the customer actually care whether their car arrives in 2, 3, 4 or 5 days?’ and realised the answer was – for the most part – no. At three-days, the customer was effectively saying, they now had enough convenience. And so, having tightened up the logistics side of the car production story, the attention shifted full-on to cost reduction. To the extent that Tier 1 and Tier 2 suppliers of components are now expected to sign up to contracts that had future delivery options tied to guaranteed cost reduction targets. The fight for reduced operating costs has become vicious. It has also, in order to enable maximisation of these cost reduction demands, caused the industry to become very strongly interdependent. Having components lying around the factory as inventory is very ‘expensive’, and so every OEM insisted on ‘Just-In-Time’ deliveries from suppliers. Armies of Six Sigma black belts get trained. All of them told that variation is bad, and that their job is to remove it. So everything gets segmented into manageable chunks and the boundaries between chunks get frozen. Then came Lean-Six-Sigma black-belts. Now, ‘waste’ was added to the list of bad things. In fairness to the originators of Lean, their definition of what waste was and wasn’t was quite broad. One of them, for example, was the waste of a ‘lost customer’. Alas, the Lean Six Sigma blackbelts stuck on the production line had no control over what customers did and did not buy, and so this ‘waste’ got conveniently swept under the carpet, and the focus shifted to the wastes found on the production line. At first there were lots. Then came the ‘lean with consequences’ phase. This is where teams realised that when they removed what they thought was waste created an unexpected adverse consequence somewhere else. Probably in somebody else’s silo. So then there was no choice but to work across silos and derive even more coupled solutions. To the point where eventually no-one has any wriggle room any more. That’s when teams start going around in circles. And the innovators give up. I remember a project with a Tier 1 supplier of gear-shifts. They wanted to get some electrical power into the gear-shift in order to add some potentially valuable new functionality to drivers. Alas, getting a 12v cable into the gear-shift meant passing it through various other parts of vehicle real-estate that came under the control of other Tier 1 suppliers. Attempts to negotiate with the other Tier 1s responsible for these other bits of real-estate quickly showed that a win for the gear-shift meant only downside for the other bits. End result: no innovation. Multiply that to include every other massively optimized, massively over-coupled vehicle sub-system and component and what you end up with is complete paralysis and, today, a sector that is amongst the worst innovators on the planet. This is the Dodo-Lean stage. Not only does innovation become increasingly impossible, but, resilience decreases exponentially (https://www.darrellmann.com/dodo-lean/).

Only healthcare, education and financial services are worse. Mainly because they’re even more over-coupled. Perhaps the all-time iconic example of the over-coupling that emerges when cost reduction is taken past the ‘with consequences’ phase and into the Dodo phase is the 2008 GFC-triggering US sub-prime loan market. Bundling together lots of crappy, ill-advised, un-vetted loans into bundles to ‘reduce risk’ turns out to be a way to massively increase systemic risk. And offers up ample proof that over-coupling results in people looking after the pennies thinking the pounds will look after themselves, without realising that this aphorism doesn’t make sense in a complex interdependent world.

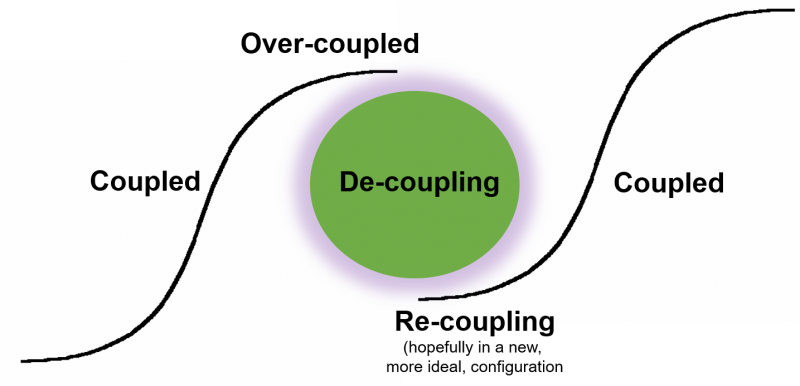

In theory, the GFC was a way of creating the sort of crisis that is often needed in order to stop the over-coupling effect. What’s supposed to happen when a system makes the discontinuous jump from one s-curve to the next is that everything has the opportunity to de-couple. Everyone realises that the current rules don’t apply any more and that the crisis offers permission to go and explore new and better ways of doing things.

Except that’s not what happened after the GFC. Instead, regulators imposed even more rules and constraints. And thus added even more coupling effects into the industry. This was called ‘kicking the can down the road’ by most economists and commentators, but from an S-curve perspective, what it really ended up being, was an even bigger accident waiting to happen. The industry over-over-coupled and thus made itself even more vulnerable to external disruption. As we’re perhaps already beginning to see in the form of a perturbation called Covid-19.

Whether the financial world has learned the lessons of over-coupling I’m not sure. I suspect not. This time around, however, Covid-19 is a toppling domino that looks like it could easily topple several others. Covid-19, too, looks like it has pushed the world off its current S-curve. Which means that at least some of the other toppled industry dominoes will do what’s supposed to happen during a crisis. The rules get re-written. First up, de-coupling happens because when some organisations realise they can’t survive stuck in their current over-coupled world, they have to get inventive and go find other ways to earn their way in life. The flashlight company that switches – in 8 days no less – to becoming a hand-sanitizer producer. The automotive OEM that sees car sales plummet and realises their stark choice is to either close the doors or finally do what customers have been demanding for at least the last decade, and start offering ‘mobility’. Something that companies like Uber, Ola and Lyft have understood since their disruptive inception, of course. A shift that the current over-coupled automotive industry has been scared of even contemplating.

The de-coupling transition phase between one s-curve and the next is rarely pleasant. When the transition in triggered by crisis, it is never pleasant. Except, of course for the innovators – that small cadre of people that live their lives in the between-curves limbo world – since they now find themselves in their element. Lots of great problems to solve, lots of exciting opportunities to exploit. Lots of rules they have permission to break. The innovators know that whoever makes it through the de-coupling transition gets to be the one who determines how the world re-couples during the early phases of the new S-curve. Given that the typical societal S-curve duration is around 80 years (https://www.darrellmann.com/history-rhyming/), whoever de-couples and re-couples the best, gets to live a comfortable life for the next 50+ years… before they too succumb to the ‘inevitable’ temptations of cost reduction and another round of over-coupling. History doesn’t repeat, but, as the over-couple-de-couple-re-couple pattern shows, it very definitely rhymes.