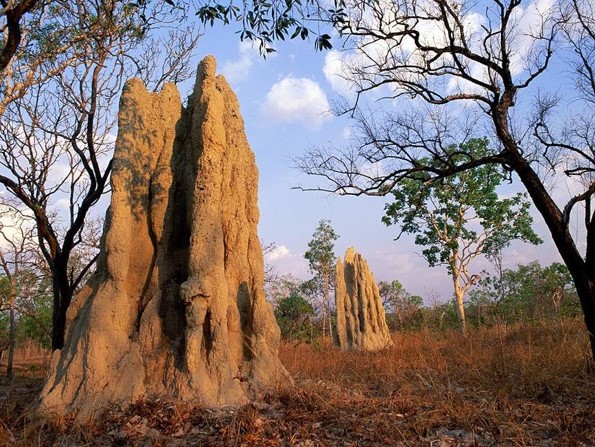

Termite mounds are often held up as examples of emergent structures. How a set of simple ‘instructions’ hard-wired inside the termite brain can produce enormously complex structures.

Every termite mound is different.

But not so different that a passerby wouldn’t recognise it as a termite mound.

A lot of people skirting in and around the world of complex systems make proclamations to the effect that no outcomes are predictable in a complex environment.

The similarity of termite mounds reminds us that this is not completely true. It might be true enough to tell us that the best way to operate in a complex environment is by making use of iterative processes – try something, see what happens, use the results to formulate our next iteration, repeat. This I agree with. Whoever iterates best, and learns fastest wins. What I don’t agree with, though, is the idea of complete unpredictability. There’s a lot we can’t know, but that’s not the same as knowing nothing.

One termite is simple. A colony of termites is complex.

One human is complicated. Two are complex. Seven billion are complex, bordering on, and occasionally tipping into, chaos.

Is there something that happens when the levels of complexity increase that make it impossible to predict what will emerge?

Well, clearly yes, but the only meaningful way by which to even begin to answer this question is to look at what is happening at a first principles level. The small number of ‘instructions’ in the termite brain are that species set of first principles. With humans the first principles ‘instruction set’ is a little bit bigger. But not much. We all want to be autonomous, we all want to be acknowledged and ‘belong to the tribe’, we all want to feel competent, we all want to do things that are meaningful. The way you were raised by your parents will impact the way you raise your own offspring. The ‘complete’ set of these first principles is looking like a page in a not much longer book of first principles we’ve been gradually decoding over the course of the last decade.

I can’t be sure we’ve unravelled the whole story. Which is a worry. But not so much of a worry that it prevents us from deploying another first principle: if you don’t know the absolute, make use of the relative. In other words, look for stuff that has changed.

So long as the termite mound-building first principles remain unchanged, all termite mounds will look like termite mounds.

So long as the human society first principles remain unchanged, all human societies will look like human societies.

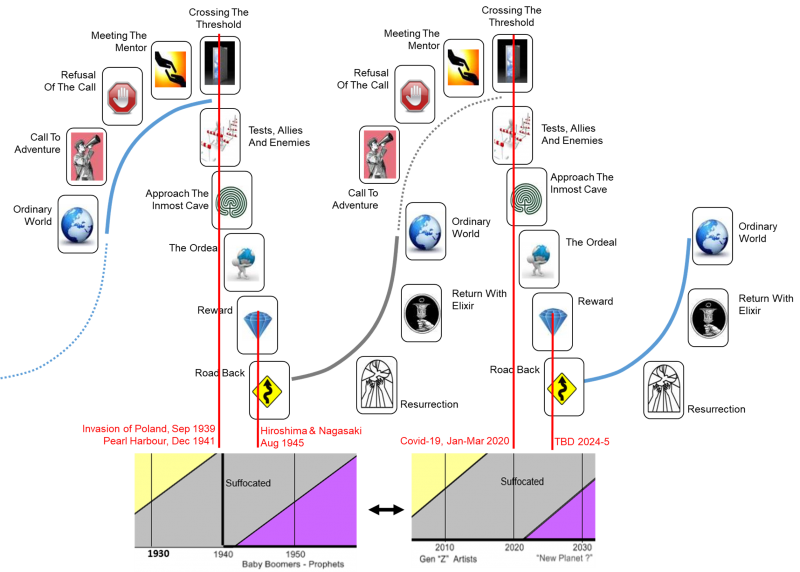

One of the most controversial of our seeing-the-future models is the GenerationDNA four-generation cycle first revealed by the work of Strauss & Howe. We’ve spent the last twenty plus years trying and failing to disprove the model. Meanwhile, during those twenty years, the societal patterns predicted by the model have all come good. Things (like pandemics) happen at random, but peoples’ reaction to those events is not random. Until such times as our collective first principles change, we will keep seeing the same patterns emerging.

Occasionally the first principles have changed. The shift from hunter-gatherer to agrarian societies, for example. Or the shift from agrarian to industrial. Or – maybe – the shift from industrial to some kind of ‘knowledge’ economy. That part we don’t know yet. What we do know, however, is that the world has jumped off its current S-Curve in the last month, and over the course of the next 3 to 4 years will make its stumbling journey to the next one.

It is during these stumbling years that we have the possibility that the set of first principles shifts. In the worst case, they shift for the worse. If the alt-right populists have their way, for example. More likely is that the pendulum swings so that a few contradictions get solved, some don’t and some new ones will appear. Consequently, some things in life will get better, some will get worse and others will stay the same. Ideally, if we embark on the journey with some kind of map, we solve the most significant contradictions so that more things get better than get worse. I’m putting my hand up for this strategy. There is a map. It’s sketchy in places, and probably a little wrong in others, but it is a map drawn from a knowledge of complex systems and first principles. Which, at this point in time, as far as I can see, are still the same ones that mankind carried 80 years ago. And 180.