Its only a matter of time before any kind of measurement gets gamed. With several of our clients, if we’re not able to convince them to go with what we think is the ‘right’ (i.e. outcome-based) kind of measurement, we at least try and help them to work out what the half-life of the measurements they intend to put in place are. So that they know when they need to start thinking about re-designing that measure. Lots of companies, for example, put into place metrics relating to the number of patent applications different departments (or in some cases, individuals) were expected to submit per year. This kind of measure typically takes about one-cycle (i.e. around a year) before it gets corrupted: ‘It’s November, we failed our target last year and got reprimanded; it looks like we’re not going to hit it this year either, so…’ You know what’s coming next.

We had a theory that metric half-life (i.e. the amount of time it would take for half the stakeholders to work out how to corrupt the measurement) would reduce considerably during a crisis period. We just didn’t know how much. On the last day of April, we got our first datapoint. And the news wasn’t good. The half-life of the Covid-19 virus test metric, we now know is significantly less than a month.

On the second of April, Health Secretary, Matt Hancock, announced, ‘I am now setting the goal of 100,000 tests per day by the end of this month. That is the goal and I’m determined that we will get there’

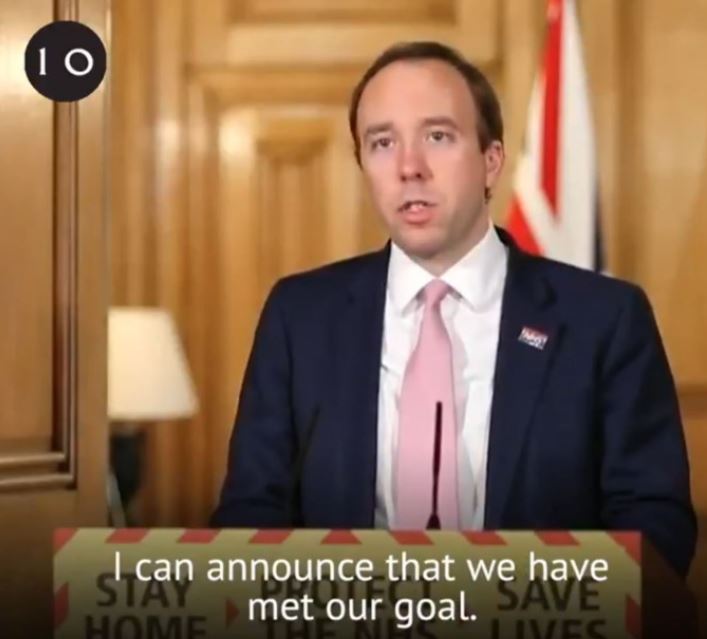

On the 30th came deliverance. 122,347 tests. Very impressive. Hancock looked almost smug when he showed up for that day’s media briefing session.

Execpt. There was a problem. Several problems. 27,497 turned out to be ‘home tests’. Tests that had been posted to people on the 30th. Another 12,872 were sent out to satellite sites. So they also weren’t actual tests either. So the 122,347 was actually just 81,978 by the 2 April definition. Then we learned that the number of actual individuals actually tested was 73,191. This because the tests aren’t massively reliable, and so large numbers of individuals had to be repeated. And then, worse still, now we also have figures for the early days of May, we also know that the 30 April figure was a one-off high.

I’m not blaming Matt Hancock for this corruption. He’s just the poor sap that set a target he didn’t understand. And he’s just the Minister putting pressure on everyone beneath him to make sure the target was met. A classic, ‘don’t let me be seen to have missed this target’ kind of pressure. Pressure that meant, as soon as said staff worked out they were going to fail, they were forced to start getting creative. Some kinds of creativity are good. But, generally speaking, not the kind where stupid things get done in order that some arbitrary target is reached.

So, May 5th, and here we are. The half-life of a UK Government metric looks like it is, if we take into account the time until someone worked out that posting home-test kits on the 30th might help, is around a fortnight. And yet still somehow the Government approval rating is above 50%. Which, if I had any faith that that particular metric hadn’t been corrupted several eons ago, I might start to worry about.

What we’ve managed to do with the clients that have had their ‘number of patent applications’ metric gamed is helped them to introduce a better ‘number of hgh quality patent applications’ measure. It’s hard to measure ‘high quality’, but the difficulty of doing it should be no impediment to working out how to do it. The same applies regarding virus testing. It shouldn’t be about how well the Government sends out unreliable home-testing kits to random individuals (and, by the way, I know from several friends that there is a massive element of randomness), it should be about the number of high-quality test results obtained. I think, maybe, everyone assumed that’s what Matt Hancock meant on April 2nd. That part of the measurement challenge isn’t rocket science. We all instinctively know what meaningful is. We just need to get those responsible for making the measurements re-direct their creativity away from gaming the system, and towards finding ways to measure what is needed rather than what is merely expedient.