So now we know. Smart motorways aren’t. Smart motorways are the opposite. Smart motorways kill. Thirty-eight people so far.

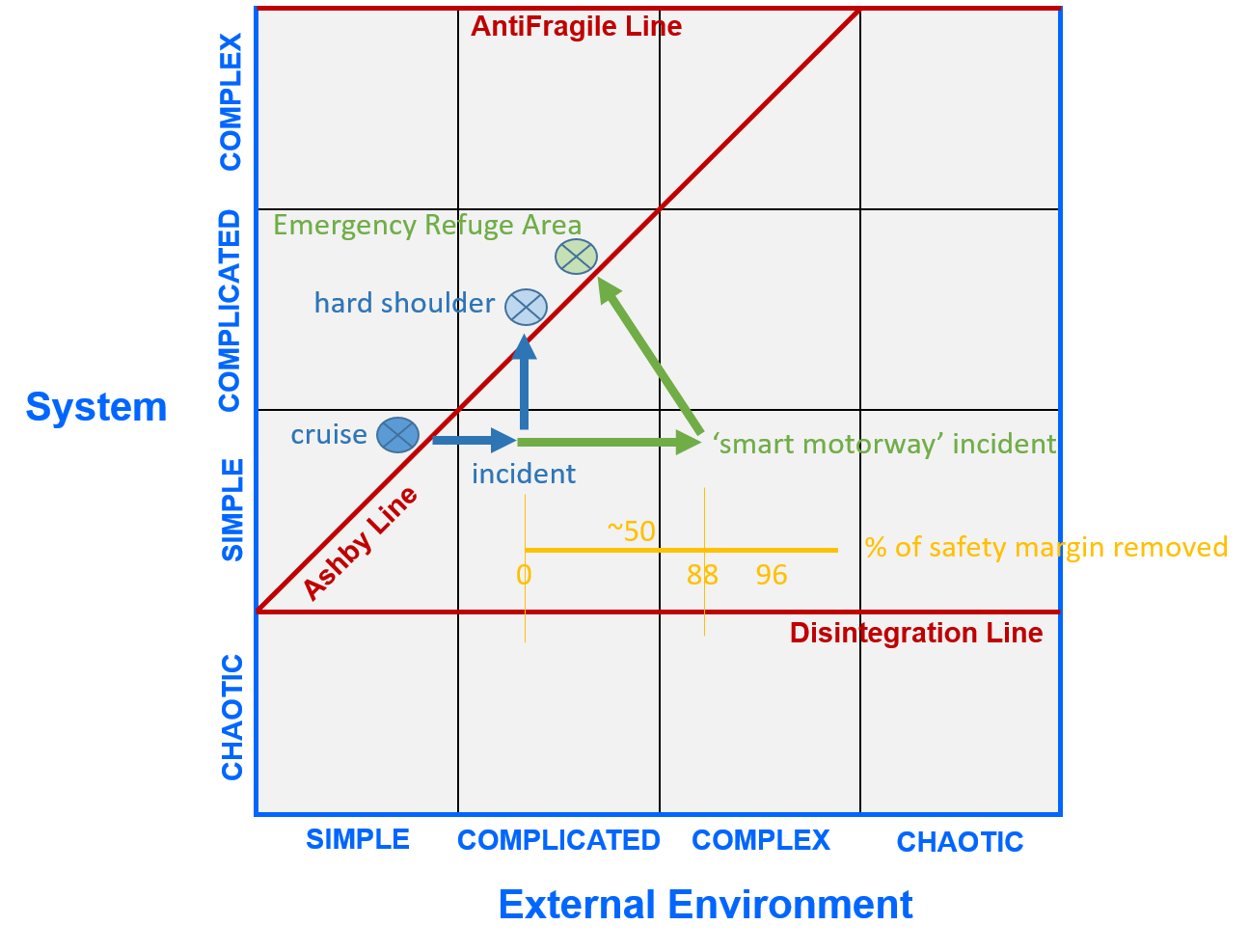

When the Government decided it was prudent to remove 96% of the safety margins on the UK’s motorways they were wrong.

Or rather, we now know, what they originally approved was the removal of 88% of the safety margin. And then subsequent bean-counters decided that they’d save even more money if they removed a further two-thirds of the planned Emergency Refuge Areas.

Now, I’m not privy to the calculations that got made in either the 88% or the 96% justifications, but given what I do know about risk, if I had to make a bet I’d say that neither solution was safe.

So, what do we know about humans and risk?

Humans make mistakes. The likelihood of failing to notice a major crossroads while driving is around 0.05%. The likelihood of leaving your indicator light on is about 0.3%. The likelihood of failing to notice another driver’s indicator is about 10%. The likelihood of making a mistake when stressed is 25%. The likelihood of failing to act correctly after 1 minute in an emergency situation is 90%. (https://www.lifetime-reliability.com/cms/tutorials/reliability-engineering/human_error_rate_table_insights/)

If a person is cruising along in the fast-lane of a motorway and a tyre blows out, that gives the driver an immediate complicated problem to solve. It is complicated rather than complex because there is a clear ‘right answer’ to the problem: navigate across to the hard-shoulder as quickly and as safely as you can.

Drivers of the vehicles behind the vehicle with the blown tyre also have a complicated problem to solve. They too have clear right answers to their problem: don’t hit the other car; decelerate; if it’s safe, switch to another lane.

We’re in 10% failure likelihood territory here. As I’ve mentioned before, most traffic accidents occur not because one person makes a mistake – we all make mistakes all the time – but because two or more people make a mistake simultaneously or within a few seconds of one another. Burst tyre problems don’t result in accidents 10% of the time. They might result in accidents 0.1×0.1 times. Or about 1%. And because everyone is slowing down, the likelihood of an accident causing injury is much lower still.

Remove 88% of the hard-shoulder, and I believe this kind of problem situation flips from complicated to complex. There is no such thing as the ‘right’ answer any more. Instead there are just heuristics: look for signs to let you know how far away the next Emergency Refuge Area is; put on your hazard warning lights; try and navigate across to the inside lanes; try to keep going until you reach the next ERA; if you can’t keep going, stop the vehicle; do not try and get out of the vehicle; phone emergency services to let them know what’s happened; cross your fingers and hope this stretch of smart motorway has radar detection switched on so the red-cross sign will tell drivers to leave the lane you’re stuck in; if the radar isn’t switched on, brace yourself for an (average) 17 minute wait for the emergency services to come and rescue you.

Moreover, it is clear that most drivers don’t know what all of the desirable heuristics are in this new world of smart motorways. So the driver with the blown tyre is highly likely to do something wrong. Now we’re in 90% error-rate territory. Which, if we take the ‘it-takes-two-to-tango’ factor into account and assume the following drivers are in 10% error mode, still means that its 0.9×0.1 = 9% likely there’s going to be an accident. The fact everyone has a heuristic saying ‘slow down’ is the only thing preventing a lot more than thirty-eight deaths so far. To calibrate ourselves a little bit more here, what we also all now know is that on one particular stretch of smart motorway, in the five years before the road was converted into a smart motorway there were just 72 near misses. In the five years after, there were 1,485.

When it comes to safe motorways, turning complicated problems into complex ones is what I think I’d have to say is the precise opposite of smart. Spending billions of pounds to make them less smart then feels rather like adding insult to injury.