MAITRE D: And finally, monsieur, a wafer-thin mint.

Mr. CREOSOTE: Nah.

:

MAITRE D: It’s only wafer thin.

Mr. CREOSOTE: Look. I couldn’t eat another thing. I’m absolutely stuffed. Bugger off.

MAITRE D: Oh, sir, just– just one.

Mr. CREOSOTE: [groaning] All right. Just one.

Rule #1 with my friend Ancient Steve is don’t phone him at home early evening during the week. I’m not sure he knows about this rule, but I think all of his other friends have worked it out too. The rule, so far as I could establish it was an actual rule, started about a year ago. The change happened suddenly, though, and that’s the point of this post. How small changes can create non-linear change. How one last straw comes to break camel’s back.

Phone Ancient Steve up on a Wednesday evening now and, if he bothers to answer the phone at all, what you’ll hear on the other end of the phone is a gruff, curt, borderline offensive ‘what do you want this time?’ kind of hello. The same call a year ago would have been answered by normal Ancient Steve. Still a bit gruff, but gruff in a pleasant enough tone that you knew he wasn’t going to snap your head off.

Somewhere between the two, something happened.

What it turned out happened is that, because Ancient Steve doesn’t believe in things like phones with caller id on them or going ex-directory, when someone calls him, he doesn’t know who it is on the other end of the line until he picks the phone up.

Now the brain is really just a big old prediction engine as far as most of our lives are concerned. All those neurons are there to anticipate what’s going to happen in the next half second. This is a good thing to be able to do from an evolutionary survival perspective. It also means that, when the phone rings, our brain immediately gets busy anticipating who’s going to be on the other end of the line.

Prior to tweleve months agao, when Ancient Steve’s brain was making that prediction, the weight of probability was that the person on the other end of the line was going to be friendly, and so Ancient Steve was able to flood his response system with ‘be-polite’ chemicals and respond accordingly.

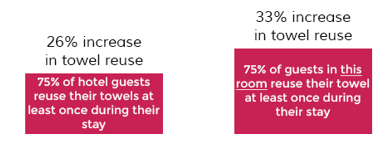

Around this time, Ancient Steve was also, it turns out, receiving a growing number of cold-calls from feckless salespeople. Early evenings during the week, the whole world of double-glazing sales personnel around the country gradually came to realise that Ancient Steve might be interested in buying replacement windows. Or a free life insurance assessment. Or a better deal on his utilities.

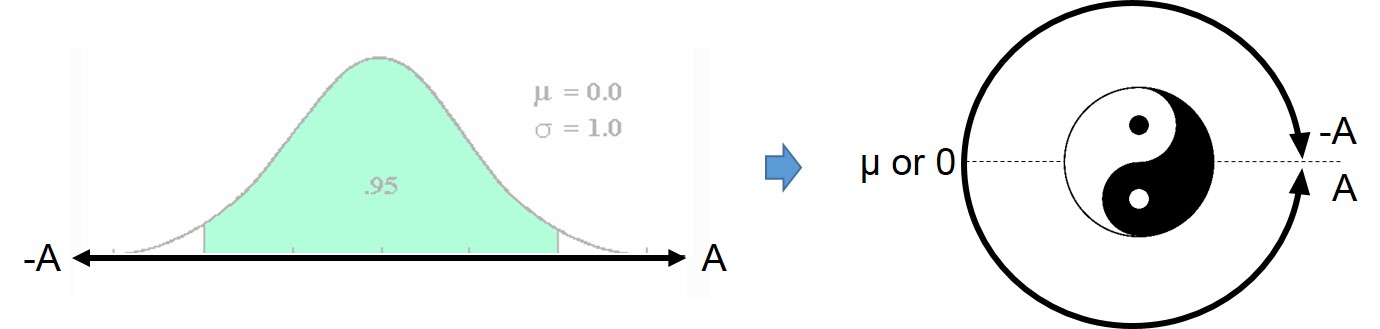

This was sort of okay until the fatal day when the balance of probabilities shifted past the fifty percent mark. When our brain does its prediction thing and tries to establish whether the incoming call is from a friend or double-glazing vending foe, the calculation is an essentially binary one. If 50.1% of past calls have been a friend, then the prediction that gets made is ‘the caller is friendly, be polite’. Ditto if the percentage is 50.01%. But, come the day that the balance of experience tips the probability the other side of the 50% mark, to 49.99%, then the default prediction becomes ‘the caller is an enemy, be gruff, surly and borderline offensive’. One call from the wrong person, one more piece of straw, tipped Ancient Steve’s behavioural balance.

And then, soon enough, they also affected mine. My prediction engine when I called Ancient Steve used to tell me, ‘here comes good old Ancient Steve’, so that I could pre-fire my own version of ‘be-vaguely-polite’ chemicals. But the moment the balance of probability in my own head about whether Ancient Steve was going to be gruff in a good way or a bad way shifted to the point where it was more likely I was going to hear the Bad version, then that’s the prediction I made.

Again, all it took was one too many calls to Bad Ancient Steve for me to change my whole view of what to expect when I phoned him.

That’s how it works. And until such times as Good Ancient Steve comes on the phone more than Bad Ancient Steve, that will remain my default expectation. Its the same thing with every other prediction calculation we make.

When I’m driving, and I see a car coming towards me flashing its headlights, my default reaction used to be to check that I hadn’t inadvertently left mine on full-beam. Then, when I realized I almost never had my lights on full-beam, my automatic, balance of probability prediction tipped to flashing my lights back at them to demonstrate that, look you idiot, I didn’t leave my full-beam on. Now I’ve lived in rural Devon for a year, the balance of probability has tipped again. When someone driving towards me flashes their lights at me now, the likelihood is there’s a silage-toting farm vehicle around the corner.

Strange that one wafer thin mint too many, as with Mr Creosote, can have such a non-linear results.

And, stranger still, even knowing all of this, is wondering how come after nearly a year of trying I haven’t managed to sell Ancient Steve any double-glazing yet.