Once in a while I find myself building a model to help explain an idea or principle to a client. The emphasis in these situations is usually to build something quickly. Which in turn usually means not worrying too much about consistency with other spur-of-the-moment models. Most of the time this works out okay. Sometimes a model takes on a life of its own and finds its way into the language with several different clients. For some reason its often the colour aspect of the models that helps with its spread. And that’s where things can easily start to turn out not okay.

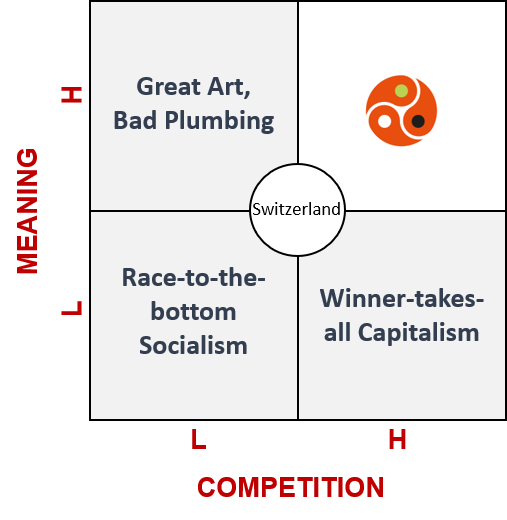

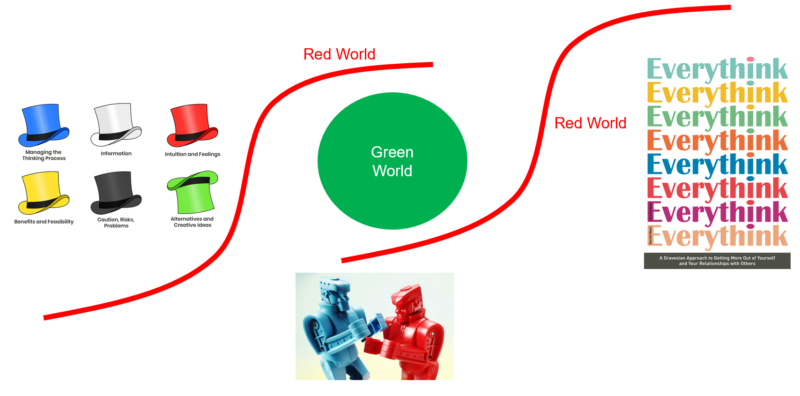

The most recent series of colour clashes have come through the Red-World/Green-World discussion I started in the wake of the Innovation Capability Maturity Model book. An attempt to get people to recognise that Operational Excellence (‘Red World’) and Innovation (‘Green World’) are polar opposites. After I’d decided I needed a model to compare and contrast the two Worlds, I spent about 5 minutes thinking about the best colours to characterise them. The logic behind the use of green was, a) green is the colour of the ‘creativity’ Hat in Edward DeBono’s Six Thinking Hats model, and, b) green is the colour of the Systematic Innovation logo. Having chosen green, and recognising that I needed a second colour to describe green’s polar opposite, I went to the colour wheel and, hey presto, red was that colour. Decision made.

Spool the clock forward a couple of years and the colours of the different Value Systems in the Everythink book also started to connect with a number of clients. Which meant the arrival of questions like, ‘is the green of Green World the same as the Communitarian green found in Everythink?’ To which the answer, sadly, is no it isn’t.

Then someone else hears me talking about the Intel-initiated, only-the-paranoid-survive idea of companies comprising a Red Team and a Blue Team. The Blue Team being the majority of people in the existing business, and the Red Team being a small group of lateral thinkers whose job was to try and find ways to put the Blue Team out of business. Now the colour problem becomes much worse. Now I find myself describing how Blue Team lives in Red World and Red Team lives in Green World. And, worse again, that Red Team people in Green World will work best if they they’re thinking with the Yellow value system. It was only small consolation to then be able to say that they should be wearing Green Hats most of the time.

Act in haste, repent at leisure.

Innovator’s live in Green World, wear Green (and sometimes Black – like baddies) Hats, have Yellow value-systems and one of their roles is to act as a Red Team.

Operational Excellence workers live in a Red World, wear mainly White Hats (like goodies), ideally have Blue value-systems and are Blue Team.

Not that it helps an awful lot, but if I had my time again I’d re-label Red-World and Green World as, respectively, Blue World and Yellow World. That way at least there’d be a consistency between ICMM and Everythink. And that would then just leave the tiny inconvenience of having companies like Intel and people like Edward DeBono in the world. Messing things up as usual. With their Purple ways.