One of the sad consequences of a world in which no-one knows what is real and what is made-up is that it becomes increasingly difficult to have a sensible conversation about anything. Is gender binary or non-binary? Is being a member of the EU a good thing or a bad thing? Instead of answers we drown in noise.

Maybe the heart of the problem is the word ‘or’. Which implies a contradiction. Which in turn is trying to tell us that we could have a much richer, infinitely more meaningful conversation if it was somehow possible to separate the contradictory sides of the argument. One side of the argument could be ‘wrong’ of course – especially in a world where students are being taught that their opinion is somehow equivalent to fact – but it is also highly possible that both sides of the argument could be ‘right’. A contradiction is when one right meets another, different, right.

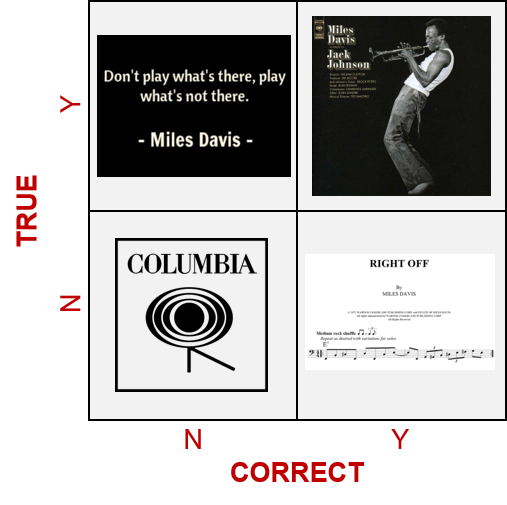

One of the least well used means of synthesising a contradiction-busting higher ground involves exploring the differences between correctness and truth.

Correctness is all about tangibly measurable properties. A tomato is a fruit.

Truth is all about the experiential aspects of phenomenology. It is about knowing whether or not it is a good idea to put the tomato into my fruit-salad.

Truth and correctness can be the same thing, but we’ll only establish whether this is so by escaping from our day-to-day existence and allow ourselves to think.

I struggle to get myself into the zone where I can achieve such thinking. More often than not, if I get there, it will be while listening to or playing music. And more often than not I’ll find it easier to get there while listening to Miles Davis.

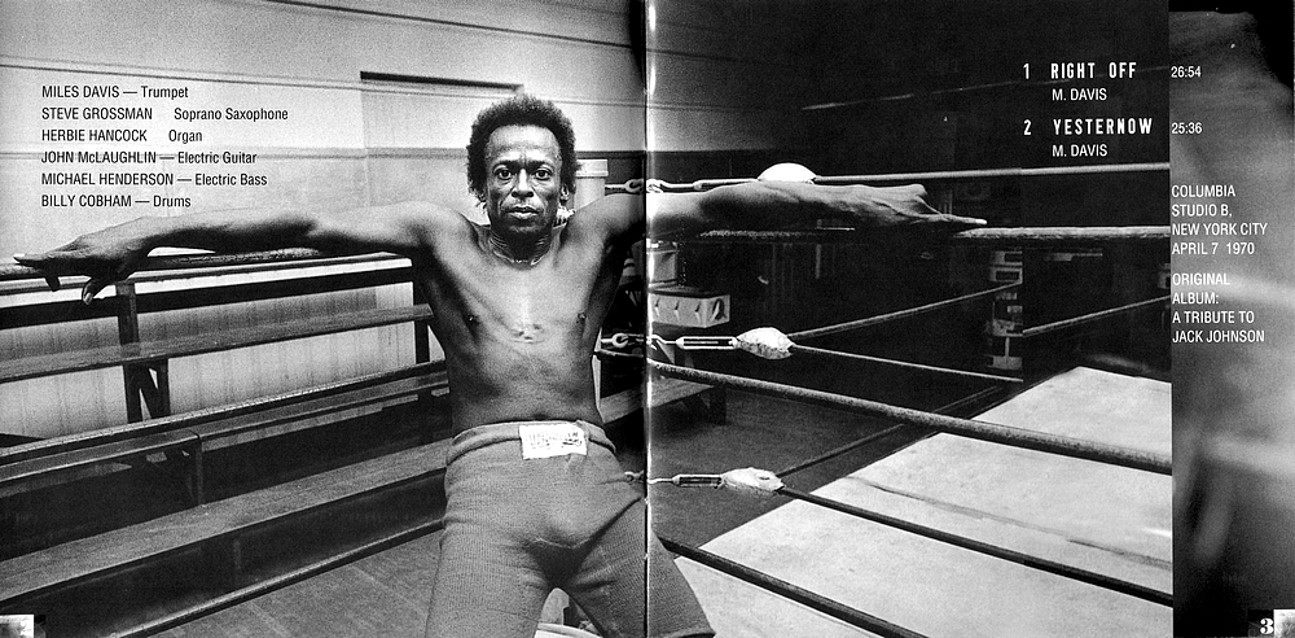

In my more naïve moments, I might take a look at a score for a piece of Davis’ music. My all time favourite of which is ‘Right Off’ from the album A Tribute To Jack Johnson. Naïve is the right word here because guitarist, John McLaughlin is about as far removed from my level of playing capability as it is possible to be. Nevertheless, if I scan the Right Off score, I can see I am looking at something that bears all the properties of correctness.

I’ll never get to play like McLaughlin. For a long time I found this a depressing thought. Then I heard the Miles Davis quote, ‘don’t play what’s there, play what’s not there’ and, after it finally sunk in, I realised I was listening to an important truth. An incorrect one from the tangible perspective of the measurable properties of the Right Off score, but truth nevertheless.

If I was looking for ‘truth and correctness’ I believe that is what the Jack Johnson record actually achieves. It is unarguably one of the most enduring and significant moments in jazz and rock history. If only for having the audacity to disrupt both so radically.

This, despite the fact that the record company, Columbia was so un-enthused by the record when Miles handed over the master tapes, they couldn’t even be bothered to check they’d put the right artwork on the album cover. Columbia, in their negligence, were neither correct or truthful. Which is kind of shabby, but does at least allow me to draw this 2×2 matrix:

And once I realise truth and correctness form two orthogonal axes like this, I might just give myself the opportunity to make some meaningful progress on whatever issue I might find myself working on.