Stock sentence of 2021: ‘intellectually, people get-it, but when it comes to reality, they don’t’. Case in point – contradictions and contradiction solving. I spend several days with a group, at the end of which almost everyone is sick to death of me hammering them over the head with the c-word. They get it. Then I see them a month later, and people are still asking either/or questions, beating their heads against walls, still be going around in circles, moving their trade-offs from one place to another, and wondering why nothing is getting better.

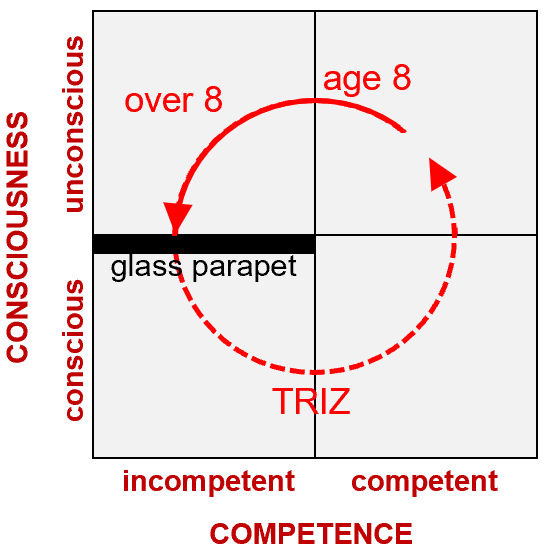

These are the times I kind of wish everyone in the sessions was still eight-years old. Eight is the age when we’re generally considered to be ‘at our most creative’. Latterly, I’ve come to realise what that really means is that when we’re eight, we still think that everything is possible. Contradiction-wise, in other words, eight year-olds are unconsciously competent. They don’t understand what a contradiction is, so they haven’t yet intellectualised the (erroneous) thought that they can’t be solved.

Alas, everything that happens to us after the age of eight teaches us that ‘impossible’ is everywhere. And that it dominates everything. This is how the real world works we get taught. You can’t have your cake and eat it. We all have to make compromises. Progress is trade-offs. After eight, we shift from contradiction-blind to contradiction-bound. And, irony of ironies, we shift from being unconsciously competent to being unconsciously incompetent. Needless to say, this is rarely a good place to be. Especially when we find ourselves surrounded by a world full of populist politicians who not only exhibit the trait, but also extol it’s virtues.

Probably best to not dwell on that thought too long.

It’s probably too late for politicians. More productive to think about ways of getting a critical mass of actual humans out of the unconscious-incompetence quadrant and into the scary-place called conscious incompetence. A place that has traditionally been fairly easy to hide from. Contradiction-wise, for the last forty years, it has been relatively easy to hide behind the parapet. Far easier to keep our heads down and do the ‘continuous improvement’ optimisation work Japanese manufacturers taught us all was important back in the 70s. Except, we now know that it’s not possible to continuously improve for ever. Sooner or later, a pandemic comes along and shows us the error of our ways. Continuously improving your way along a dead-end road isn’t nearly so much fun when your nose ends up pressed against a mile-high, million-tonne parapet with a ‘no further’ signing hanging off the crenellations, and there are thousands of people still pushing you forward.

They say change only happens when there’s chaos. A fact Steve Bannon and his nut-job cronies were all banking on. A fact that, I suspect, the puppet-master pulling Bojo The Clown’s strings are still kind of banking on. Chaos happens, more and more people are beginning to see, because we’re all very, very visibly incompetent.

We’re able to intellectualise ‘win-win’ solutions, but we don’t know what they feel like in reality. Or how to make them happen. Everything we’ve been taught is wrong. Literally wrong.

The million-tonne parapet is transparent. That’s what everyone that bravely makes the leap into conscious incompetence is able to look back and see. A mile high wall of pressed noses hiding behind a wall they can’t see is transparent.

No-one likes being wrong. Innovator’s, however, have learned that being wrong is an essential part of the process. And that it’s okay to be conscious of your incompetence. The pain that comes with that knowledge is the pain that drives you forward to try and become less incompetent. It’s the pain, too, that eventually brings the realisation that true progress starts with finding contradictions and continues by then persisting until they’re solved. This is the main learning of TRIZ. Or the Theory Of Constraints. Or Edward De Bono’s parallel thinking. Learnings that, until now, most people have filed away in the ‘intellectual-curiosities’ part of their brain.

Now, though, is the time to stop hiding behind the parapet. Those that have admitted their contradiction-incompetence can see you. They’re waving to you. Beckoning. ‘This way,’ they’re miming, ‘don’t worry, it’s not so bad. All you have to do is remember back to when you were eight. Impossible was nothing back then. And it can be again. All we need to do is tap into the knowledge of those that passed through contradiction-incompetence before us. Those brave souls that now realise, whatever the contradiction, someone, somewhere already solved it. Someone that became consciously contradiction competent. And maybe then went one step further and used that competence often enough to re-train their instincts sufficiently to make it unconscious again. Like when we were eight. Only now with the added ability to distinguish the genuine breakthroughs from the currently impossible.