Speed wins in a crisis. We knew that. One of the consequences is our collective societal knee-jerks more often than not mean we end up doing dumb things quickly.

Every time I do our ‘save the Titanic’ exercise in workshops, within 5 minutes every group ever has found all of the resources that would ever have been needed to keep all the passengers and crew alive. And yet, on the night, 1500 people died. Death by, in some cases quite literally, jumping before thinking.

Fear and confusion does this to us. Ready, fire, aim. In crisis times, the job is to try something, see what happens, learn from it, and try again. Crossing your fingers that the thing you tried doesn’t turn out to be so dumb that you don’t survive the experiment. Fire before aim. I get it.

But when Tom Peters first popularised the aphorism, even though he switched ‘fire’ and ‘aim’, he still left ‘ready’ at the start of the process. Like with the Titanic exercise, ‘ready’ is all about that five minutes at the beginning where we take a deep breath and think logically and rationally about the situation.

You can be fairly certain this ‘ready’ stage hasn’t really happened when we start to hear conflicting advice from experts. This is what we’re seeing at the moment regarding masks.

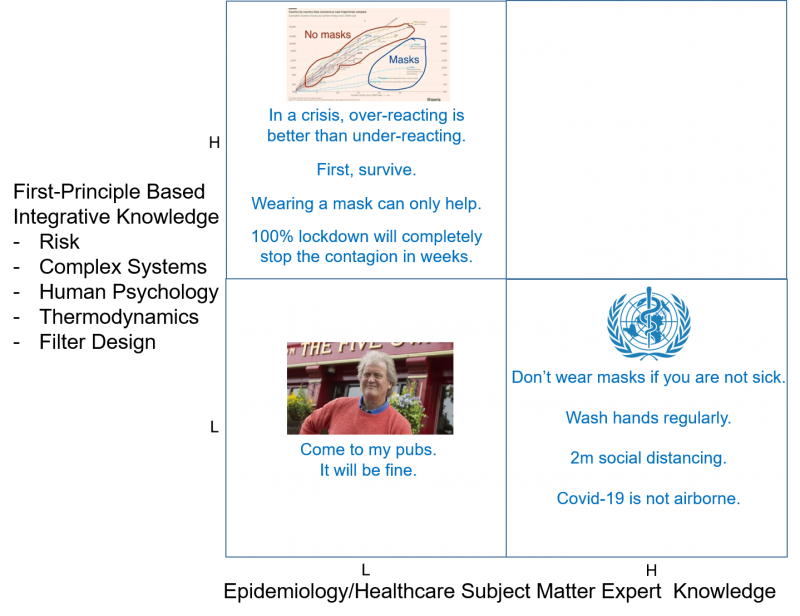

The World Health Organisation is telling people, ‘don’t wear masks if you’re not sick’. On the other hand, those that understand systemic risk say wearing a mask ‘can’t do any harm’ and so therefore we should do the opposite. Two separate instinctive knee-jerks that together serve only to confuse the average person in the street.

From a ‘ready’ perspective, when two smart groups of people are telling you different things that you’re probably dealing with a right-versus-right contradiction. And that contradiction needs to at least be managed before you make a personal decision regarding whether you’re going to go looking for a precious mask or not.

The heart of the contradiction is this. An argument between two different types of expert. The WHO and the epidemiology community possess lots of domain knowledge about pandemics. A lot of it is is based on statistical information.

The risk/complexity community, on the other hand, doesn’t have any domain knowledge relating to the spread of viruses, but they do know that the WHO’s statistical foundations are in reality ‘naïve probabilism’ when taken at the systemic level. In a complex environment, getting to where you want to get to (ending the pandemic) means the main basis for action is working from where you are to where you want to get to with heuristics that present a change vector that progressively gets everyone pointed and moving in the right direction.

The two perspectives – subject matter expert domain knowledge and integrative risk and complex systems knowledge – can be presented as a 2×2 matrix like this:

What the matrix ought to remind us is that where we need to try and get to is the top right hand corner. Answering the mask question is not about picking a side in the either/or debate, it is about solving the contradiction between the two differing perspectives and thus getting the best of both worlds.

If we’re going to do this properly, the integrative-knowledge axis of the plot needs to include all of the ‘out-of-domain’ knowledge that is relevant and not included in the domain knowledge axis. So, in addition to understanding risk and complex systems, we ought to add to the list things like human psychology and, in the case of the Covid-19 virus, some knowledge of virus and droplet aero/thermodynamics and, if we’re thinking about masks, the design of filters. Now we’re presenting ourselves with a pretty tall order. In order to meaningfully answer the ‘should I wear a mask?’ question we need someone with the requisite level of knowledge of epidemiology, risk, complex-systems, human psychology, thermodynamics and filter design. I don’t think there are too many of those people around.

Or maybe there is. Maybe this is where TRIZ/Systematic-Innovation comes into the story. The basis of the TRIZ aphorism, ‘someone, somewhere already solved your problem’ is that the whole method is built from knowledge accumulated by looking across all of the world’s different domains. It offers a first-principles synthesis of everything.

As someone that has used TRIZ for the last 30 years and been developing it for the last 25, while I can’t claim it has made me an expert in any of the needed domains, it has enabled me to go and find the experts and ask them the right questions.

What this then means is, to take a first example, looking at the WHO declaration that Covid-19 is not airborne, but is rather transmitted in droplets of saliva and mucus. Big droplets don’t stay airborne for very long, and will not travel much more than 1m from their source (hence the 2m social distancing rule – 1m plus safety factor).

As far as they are concerned this is statistically true. But, when we bring a little thermodynamic knowledge to bear on the problem, we have to also take into account the fact that the liquid that forms the droplet will inevitably evaporate. The rate at which this will happen depends a lot on ambient temperature, pressure and air movement. A typical 50micron water droplet will evaporate on a typical UK Spring day in around 120 seconds. If the droplet is on, say, the surface of a mask that is being breathed through, the evaporation rate will be significantly higher, and so the droplet will evaporate in around 60 seconds (this is an experiment that’s fairly easy to reproduce yourself… sneeze onto a surface that allows the resulting droplets to be visible (I used a piece of slate) and see how long they take to disappear, first by just leaving the slate to dry, and second by blowing on it).

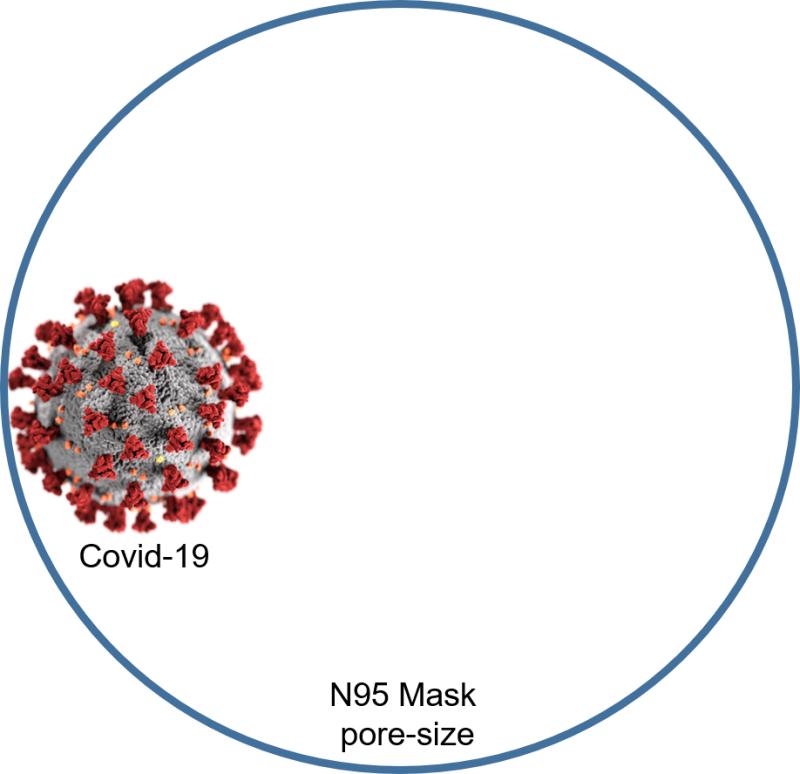

The importance of this is that after less than two minutes, the droplet that was carrying the virus has evaporated, leaving the virus exposed. This being the case, there is now a question about whether it is able to become airborne. Whether or not this is going to happen, again depends on a number of factors, some of them relating to the ambient conditions and some relating to the virus itself. Now, the aerodynamicist needs to know the size and density of the virus particles. The data is still coming in as far as Covid-19 is concerned, but reliable reports (Reference 1 from South Korea) suggest a diameter of between 70-90nm. This is small. So far I’ve not been able to find any figures on the specific volume or density of Covid-19 – which in itself is a worry, because it means the epidemiologists don’t think this knowledge is important. It is important.

If we don’t know the specifics of Covid-19, we do know the details for other corona viruses. Their density is around 1.37g/cm3. Asuming Covid-19 is in the same ball-park, this tells us that, yes, Covid-19 will very definitely become and stay airborne. Like for like, it is slightly worse, but similar to cigarette smoke.

What this now means is that, the sneeze that lands on the ground will evaporate after a couple of minutes and allow any wind to lift the virus particles up and blow them into the atmosphere. Once up in the air, they are very likely to stay there for some time. Now the issue becomes how long they will continue to be viable. Another current unknown, although figures of between a few hours and a day are circulating.

More importantly, as far as our mask problem is concerned, is recognising that a sneeze droplet from someone else’s sneeze landing on the mask I might be wearing will evaporate after less than a minute, leaving the virus particle itself on the surface of the mask.

So, now the question becomes whether this virus can get through the mask and into my mouth. Now we need the filter designer’s knowledge. Will a 70-90nm diameter virus get through the mask filter? Fairly obviously, the answer to this question depends on the mesh size of the filter. There’s been a lot of mention of the N95 type filter in recent days. The ‘N95’ designation means that when subjected to certification testing, the respirator blocks at least 95 percent of very small (0.3 micron) test particles. Which basically means, to a Covid-19 virus N95 looks like lots of really big holes. The equivalent of throwing a tennis ball through a basketball hoop. N95s will absolutely stop sneeze droplets from entering the wearer, but after the moisture has evaporated, the remaining virus particles will easily get through the mask. If not on my next breath, a later one.

This is not to say that the N95s are useless, but what it does mean is that if you’re wearing one in the vicinity of a sneeze, you’ve got about 60 seconds to change it for another one (ideally sterilising the old one rather than throwing it away) if you want to stop virus transmission.

We could go on to talk about sealing around the sides of the mask – another significant design flaw in most masks – and we could also look at load factors (i.e. how many virus particles does a person need to ingest before they’re likely to become symptomatic and get the disease (about 10 is the emerging knowledge, but we still don’t know for sure)) but I think we should now say ‘so much of the hard science’. Now let’s have a look at some fuzzy human psychology. The risk/complexity world says we should all wear a mask because, ‘it can’t do any harm’. While this might be factually true if humans were 100% reliable automatons, the reality is that a number of very human quirks come into play.

The first is that, when we’ve taken a precaution we think is going to work, we think we’re safe. Every safety feature car manufacturers add to the vehicles we drive, we all compensate for by driving worse. In other words, the safer we think we are, subconsciously the more risks we allow ourselves to take. Example 1: we don’t take social distancing so seriously. Example 2: we know that hand washing and not touching your face is good WHO advice. But when you’re wearing your mask, suddenly it becomes more okay to touch your face. Plus, the mask is often a bit uncomfortable and irritating, so there’s a tendency to ‘have’ to touch the mask more to adjust it. Thus, if you’re not washing your hands every ten minutes, transferring more virus to the surface of the mask.

This is where I think the risk/complexity people have been naïve. The blanket assumption ‘it can’t harm’ does not take account of the real world. The same as when they’ve been declaring that ‘100% lockdown will stop the virus completely in ~15 days’. 15ish. I can’t remember their precise number, but in reality I don’t need to because I know that there’s no such thing as 100% lockdown. In the real world people need to go out and get food. They need exercise. They get bored. We go out.

Anyway, that’s a story for another day. Today’s question is should I wear a mask?

What do we know, now looking at the world from the top-right hand both/and perspective of our domain knowledge and integrative knowledge matrix? i.e. taking into account both what the WHO says and the risk/complexity people say and adding in some actual facts that are needed to properly answer the question.

- If you’ve got symptoms, you wear whatever mask you can to help reduce the spread to others.

- If you’re working around Covid patients, you should have a mask considerably better than N95 (see the hazmat suits worn by Chinese doctors and nurses).

- If you’re the average citizen out in public (why aren’t you locked down?) unless you have a fully sealed mask with a filter mesh size less than 70nm, it is virtually pointless and will probably lull you into a false sense of security, so don’t wear one. Especially if you having one means that a medical professional doesn’t get them because you’ve hoarded them all (…stop being selfish, while you’re at it).

- If you can’t get the ‘it can’t harm’ meme out of your head and are going to wear one anyway, remember not to touch your face or the mask, wash your hands regularly and change the mask (or, better, sterilise and re-use) probably just as regularly.

At the end of the day, everyone makes up their own mind on these issues. A lot of people – bottom left of the matrix – actually, it seems, don’t want the truth. Or maybe they’ve just become so jaded after several years of fake news that they’ve just decided to blank everything out and listen to whoever shouted the loudest. The sort of people that listen to prats like Tim Martin telling them its safe to go and drink in his pubs.

Ultimately, to paraphrase Nassim Taleb, don’t listen to what people say, watch what they do. When I decide to go to the supermarket later this week I have risk-taking skin in the game. Will I wear a mask? Based on the top-right hand corner of the matrix, I will not be wearing a mask.