In an average year, I probably get asked to review a couple dozen academic papers. I usually accept, figuring that if the paper is any good, I might learn something, and if it isn’t, I get to write comments that will hopefully enable the authors to learn something. In the last couple of years, I’ve noticed a distinct shift from the former to the latter category. Which basically means that either I’m getting grumpier as I get older, or the quality of the papers being written is on a sharp decline. Probably a bit of both.

July turned out to be a pretty bad month. Three reviews to do and each paper exponentially worse than the one before it. Which meant that, ten minutes after opening the third paper, I was all for picking up a baseball bat and heading off to the Journal of Civil Engineering and Management to conduct a more physical version of author learning.

This first ‘paper’ reported an exercise to translate the original Altshuller Contradiction Matrix into a business matrix. Anyone that knows me can probably already guess where this might go. Anyway, the authors tried to justify this rather stupid decision by listing a page full of references. None of which were relevant. Including the reference to one of my papers. Which, if memory serves me correctly, was trying to make the point that it was barely acceptable to try and use the original Matrix for architecture problems. Never mind project management ones. This in turn made me realise that the authors very likely hadn’t read my paper at all. Rather they’d more likely done a five minute SCOPUS search for ‘TRIZ and architecture’, then copy-pasted the results into the back of their paper, and randomly allocated some reference numbers into their equally random sequence of words. It’s better than working for a living I guess.

The second paper related to an attempted de-bunking of so-called Generation Theory. Definitely a paper that should have been up my street, since, if anyone has heard me talking about Generation Theory during workshops will know we’ve spent the last twenty years trying to achieve precisely such a de-bunking. Therein lies the only similarity in approach though. We’ve tried to use some actual science in our attempts to dis-prove the model. Whereas the author of this paper hadn’t understood the ‘theory’, hadn’t attempted to, and was instead intent on executing what the popular press likes to call a hatchet job. So we end up with an argument that goes something like: generation theory sounds too good to be true. Therefore, it can’t be true. Therefore, let’s simplify it down to something a lay-person (or ‘reviewer’) can understand. Then make a few naïve and/or disingenuous assumptions. Then formulate a meaningless research question. Then misinterpret the results. Then swing the hatchet. Publish. Rinse. Repeat.

The third paper was so bad I really don’t know where to begin. Except maybe to say that the researchers in question had very likely picked up the half-science manual by mistake when they were looking for some authoring advice. Here are a few words from the abstract at the beginning of the paper. In theory, these are supposed to be the most readable part of the paper:

Since reliability and validity are rooted in positivist perspective then they should be redefined for their use in a naturalistic approach. Like reliability and validity as used in quantitative research are providing springboard to examine what these two terms mean in the qualitative research paradigm, triangulation as used in quantitative research to test the reliability and validity can also illuminate some ways to test or maximize the validity and reliability of a qualitative study.

This word salad indeed turned out to be the most readable part of the paper. It was definitely the bit that made the most sense. To say the work was ghastly is an insult to ghastly things.

It felt like time to offer up some advice. Initially, I figured this would best be directed at the researchers, but then the more I thought about it, the more I realised my anger was perhaps better directed at the supervisors that were directing their researchers to do dumb things. Or, perhaps more likely, didn’t know the difference between dumb things or smart things in the first place (one of the hazards of becoming a career academic?). But then again, no. The current round of ‘supervisors’ are probably a lost cause by now. Any researcher worth the name should be able to work out their supervisor was deluded, dumb or distorted within a couple of weeks of starting their research. That’s what literature reviews are supposed to be about. You know, like finding out that someone’s already created a Contradiction Matrix for Business problems fourteen years earlier before spending six months doing ball-aching, nugatory work.

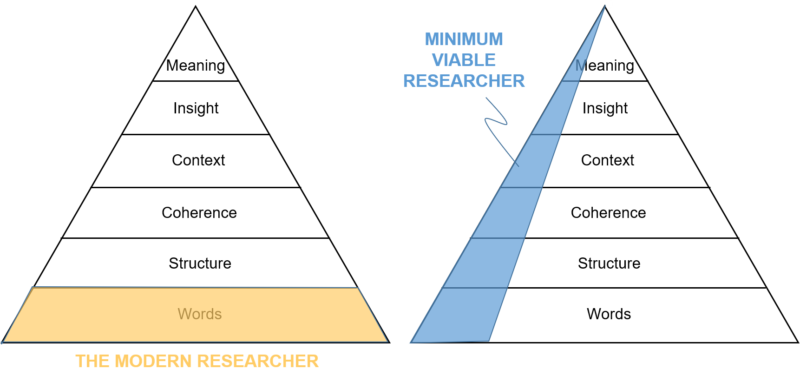

So, anyway, here’s my non-exclusive set of suggestions for a minimum viable researcher:

- A minimum two-days learning some of the basics of TRIZ at the beginning. The main aim being to understand that when we say, ‘someone, somewhere already solved your problem’ researchers not only begin to realise it is actually true, but also know how to go and find the somebody. The secondary aim being to get them to realise that research means advancing the chosen subject. Which to all intents and purposes means that if we haven’t revealed or solved at least one contradiction before we’ve finished, we haven’t been doing research but re-search.

- A minimum three days learning the basics of Complex Adaptive Systems. Enough that they can grasp some of the basic tenets as they apply to their research topic. Like, for example, to choose a contentious area, appreciating there’s no such thing as ‘clinical evidence’ when we’re dealing with a complex problem. Quite simply because its never possible to step in the same river twice. Then appreciating that it’s perfectly possible to design experiments that are less than complex and still valid, provided you understand the first-principles from which the overall complex system has emerged, and are extremely cunning with your experiment design. This then leads to…

- A minimum of two days uncovering and understanding those first-principles. Add another day to ‘really’ understand them.

- A minimum of three days on human psychology. The main purpose of which will be to equip the researcher with the necessary gumption to go back to their supervisor to tell them that the research they’ve been asked to do is pointless. And, so we don’t come across as unduly negative, that we’ve found the critical contradictions needing to be addressed and now have a plan to start tackling them.

- A minimum of three days on the science of measurement. Specifically, to learn that it is vital for researchers to measure what is important rather than merely expedient.

- A minimum three days learning about the structure of story. That way, when it comes to finally writing up the brilliant contradiction-solving piece of research we’ve just done, we don’t bore the reader shitless when they have to read about it.

TRIZ. Complex Systems. First Principles. Psychology. Measurement. Story.

Seventeen days.

All in all, quite a big investment of time. But then again nothing compared to the two years that seems the new normal as far as doing pointless re-search is concerned. Even if – and I say this because I’ve seen it apply to a majority of ‘researchers’ – your primary motivation is to emerge from the train-wreck with a bright shiny qualification, your soul will thank you for spending those two years doing something meaningful.

The (academia) king is dead. Long live the king.