One day, someone needs to make a TRIZ analysis of Nikola Tesla. Even a cursory examination of the myriad inventions he left behind gives a clear impression of a person that knew about TRIZ before there was a TRIZ. Here’s a simple illustration.

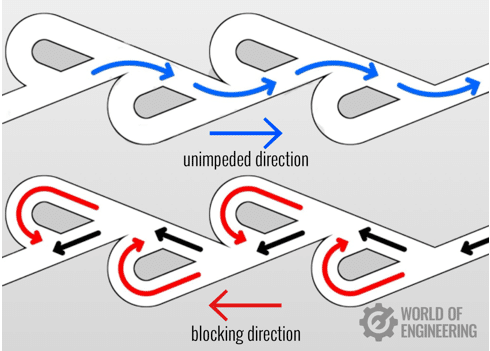

The Tesla Valve is a fixed-geometry passive check valve. It allows flow preferentially in one direction, with no moving parts. Tesla was granted US Patent 1,329,559 in 1920 for the invention.

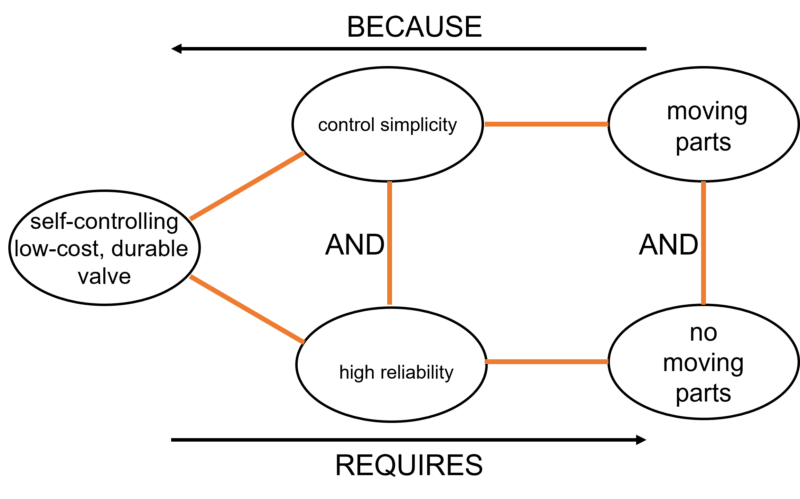

Looked at from a contradiction perspective, the problem Tesla solved looks something like this:

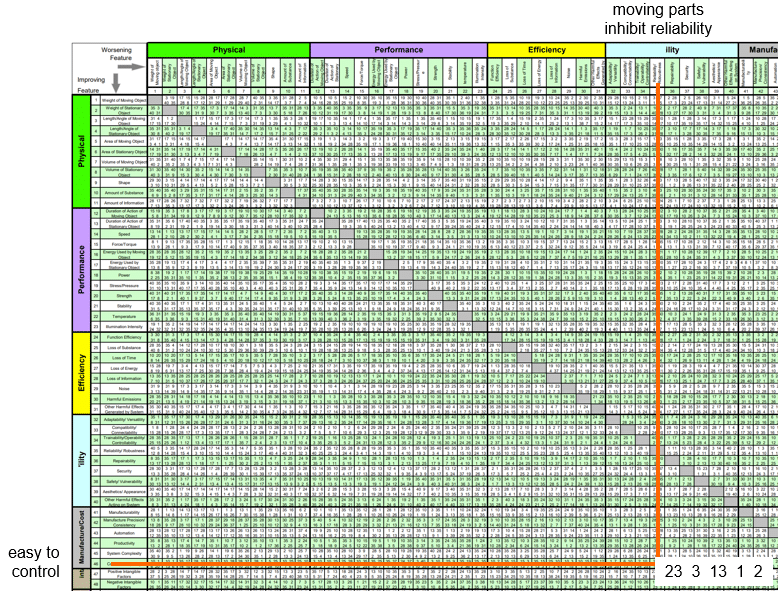

On the one hand, check-valves (traditionally) need moving parts to allow good flow control, on the other, moving parts should be avoided because they reduce reliability. Here’s what the Contradiction Matrix tells us about how people who aren’t Nikola Tesla solved similar control complexity versus reliability problems:

Sure enough, the Inventive Principle recommendations make several connections to the Tesla valve, most notably in bifurcation of the flow (Principle 2) and the division of the valve operation into multiple segments (Principle 1). We might also accept that when the flow is in the blocking direction, one of the flow channels is reversed in order to impinge on the other flow, and hence looks something like a Principle 13 strategy.

Strictly speaking, however, the key to this invention is Principle 14, Spheroidality, and specifically 14C, ‘use rotary motion’. And no matter how else we might interpret the conflict being solved – system complexity, ease of operation, adaptability, etc – a Principle 14 recommendation is nowhere to be seen in the Matrix.

No doubt Tesla’s 1920 invention will now find its way into the Matrix database for future problem-solvers to find. I’m now wondering what his other hundred plus patents might reveal. My suspicion is that if we compiled a league table of inventors using both the most and the most counter-intuitive Inventive Principles, Nikola Tesla is going to be somewhere near the top of the list. Let’s see…