Scurvy, the disease known as the plague of the Sea, and the Spoyle of Mariners was responsible for somewhere around two million deaths between 1500 and 1800. In 1769, the English explorer, Captain James Cook set sail for the South Pacific with 7860lb of what he thought might be the cure. Sauerkraut. The only problem was that the pungent fermented cabbage looks awful, smells awful and pretty much tastes awful. And so he had a problem: how to convince the crew that they should chow-down and eat their daily ration.

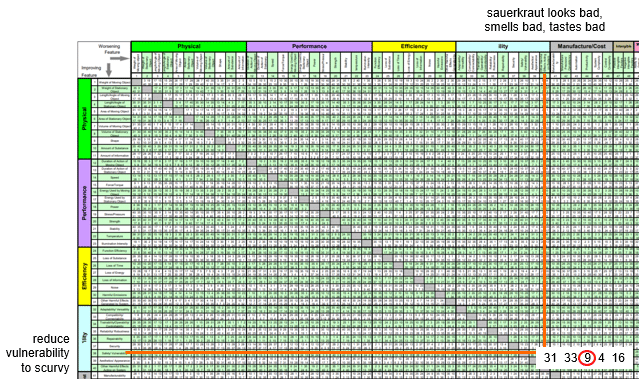

Here’s a classic contradiction situation. Cook wanted to reduce the vulnerability of his crew to scurvy but was being presented by numerous negative effects. Here’s what the Contradiction Matrix has to say about how other problem solvers have successfully dealt with this kind of problem:

Captain Cook’s solution was straight out of the Principle 9, Prior-Counteraction playbook. At the beginning of the voyage, he instructed that the foul foodstuff would only be available to the ‘Cabbin Table’ and not to the crew.

The crew, seeing the bosses eating something that they weren’t permitted to have played on their (and all of our) prestige and status needs.

‘The moment they see their superiors set a value upon it, it becomes the finest stuff in the world’, Cook wrote in his journal.

Sure enough, the lower ranked players began requesting it. Not long after that, such was the demand, sauerkraut had to be rationed.

The number of men that died from scurvy on that expedition was an unprecedented zero.