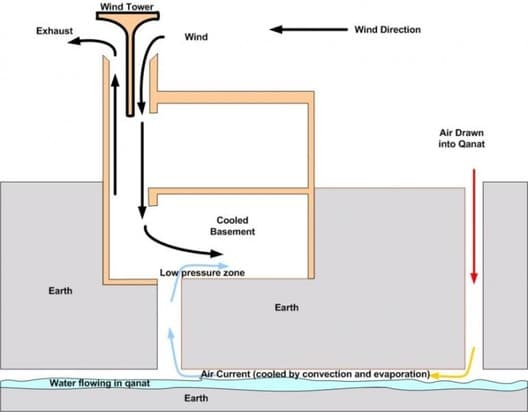

Imagine you’ve got this fantastic contraption in the heart of a Persian desert dwelling—a “badgir,” (بادگیر) they call it. A 700-year-old air conditioner capable of cooling an environment up to 12°C with no power input. Picture a slender tower, made from mud brick or whatever materials the desert provides. Now, at the summit of this tower, there’s this ingenious setup: openings, like welcoming portals, facing the insistent desert winds. Then there are a series of vertical vanes, like nature’s own air conductors.

When those winds come sweeping in, they’re directed downward into the depths of the structure. But here’s the beauty of it—a concealed channel, a kind of architectural rabbit hole, guides this wind into the living spaces below. As this invisible breeze infiltrates the dwelling, it works a magic trick: it pushes the warm air out, creating a sort of natural air exchange.

In the dance between wind and channel, the interior gets a breath of fresh, cool air, and the oppressive warmth is cast away into the open. It’s a play of pressures and flows, a symphony of desert design that, prior to a recent sustainability-resurgence architects seemingly forgot. The desert’s answer to cooling, not with high-tech gadgetry, but with the elegance of a structure attuned to the rhythms of completely natural resources.

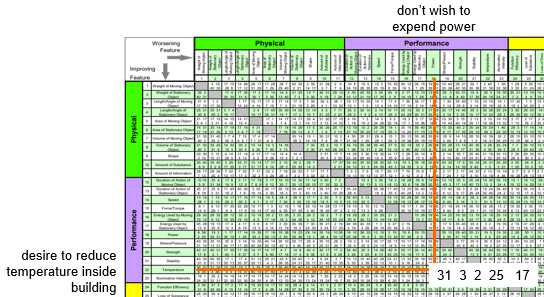

Here’s what the badgir temperature regulation versus power conflict looks like when mapped onto the Contradiction Matrix:

All in all, it looks pretty much like the architects of 700 years ago could’ve written their own version of the Matrix: Principle 25, Self-Service, tick. Principle 31, Holes, tick. Principle 2, Taking-Out/Separation (upwind/downwind sides of the tower), tick. Principle 17, Another Dimension (going underground, Qanat), tick. Principle 3, Local Quality (different rooms), tick: