One of the no-doubt apochryphal TRIZ stories concerned the consultant brought in to solve the problem of elevators for high-rise buildings. Lifting people fifty storeys into the air was slow. Passengers hated the thought of long elevator rides several times a day. The elevator company was trying to design faster solutions. They weren’t working, and they were expensive. Millions of dollars worth of expensive. The consultant offered a solution that would cost a couple of hundred dollars. A solution that is still in use today. The solution involved putting mirrors inside the elevator car. People, he realised, didn’t care how slow elevators were, they cared about losing their precious time. Once the mirrors were in place, we’re able to check we don’t have cabbage in our teeth, haven’t spilled soup over our shirt and practice our empathic smile skills. Simple.

Not that there’s a direct corollary I’m sure, but it feels to me that the huge national embarrassment, HS2, the proposed new high-speed rail link from London to what now looks like North London rather than Manchester and Leeds, a link promising to save people twenty minutes, would do well to think about the twenty-first century version of fitting mirrors rather than destroying several thousand acres of green-belt land. And spending what now looks like five times the originally estimated cost. Which is ultimately most likely the point: politicians like big, sexy projects. They like their names on plaques.

Mirrors and plaques aside, HS2 is now also the talk of anyone interested in project management around the world. As a prime example of how NOT to do projects. Whatever HS2 managers are doing, the logic now goes, good project management means do the opposite.

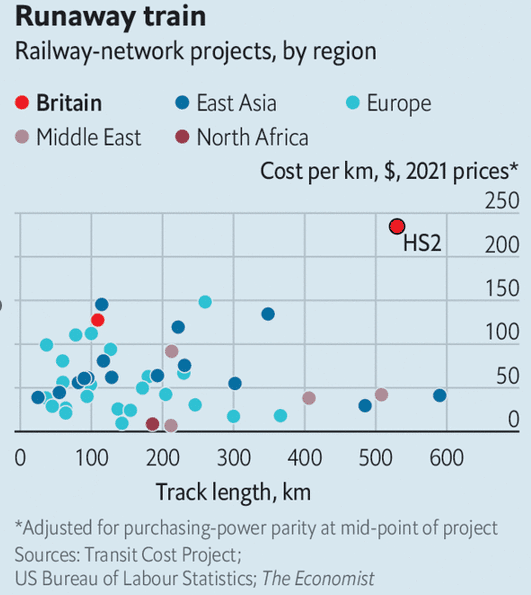

Here’s an example. The current (nobody believes anyway) estimate for the project is around £207B. Or, mile for mile, over ten times what it would have cost in Germany, and almost twenty times what it would have cost to build in China.

As is the norm these days, all the work is competitively tendered. Which in turn means that prospective contractors put in unrealistically low bids, knowing that if they put in realistic ones, they won’t get the job. They then ‘solve’ the job under-estimate problem by writing into their bids a series of Get Out Of Jail Free cards that, as soon as anything in the specification changes, opens up the opportunity to renegotiate the contract value. Only this time without the annoying competitive tender process. In summary, the result is a working environment that might best be described as ‘low-trust’.

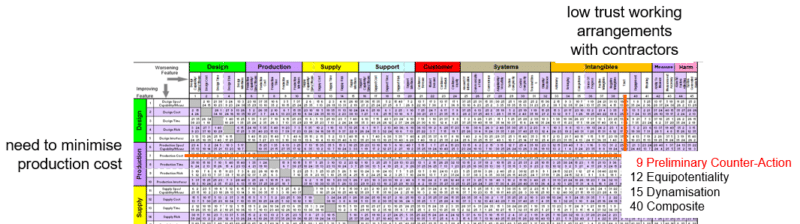

Enter TRIZ again to say that HS2 is not the first time in the world there has been a conflict between a contractor’s desire to minimise production costs and having to contract to a low-trust market. Here’s what the Business Matrix has to say about how the problem has been successfully addressed by others in similar situations:

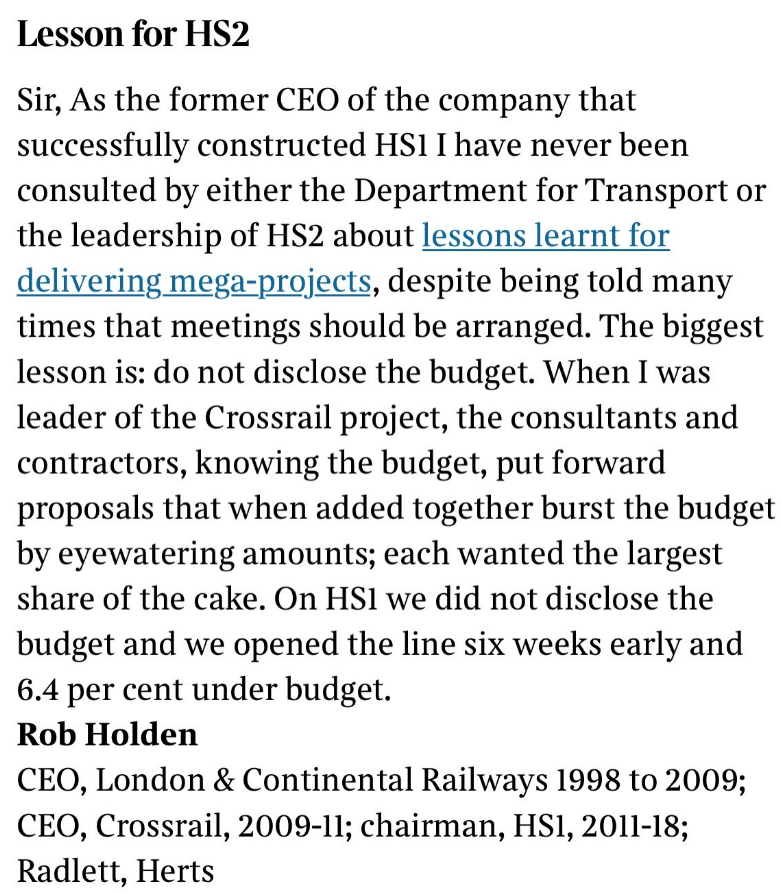

Seeing one of my favourite Principles at the top of the recommendations list triggered a search that picked up this recent letter from The Times, from the CEO of the rather more successfully managed HS1 project. Here’s what he had to say:

I don’t think he knows Inventive Principle 9, Prior Counter-Action explicitly, but the way he managed contractors during HS1 offers up a nigh on perfect illustration of the Principle anyway.

The HS2 CEO clearly didn’t know or understand Principle 9 either. Here’s hoping the CEO of HS3 (sometime in the 23rd Century most likely) remembers again. Probably aided by a Business Matrix equipped digital twin. That way we don’t miss a generation again. Just a thought.