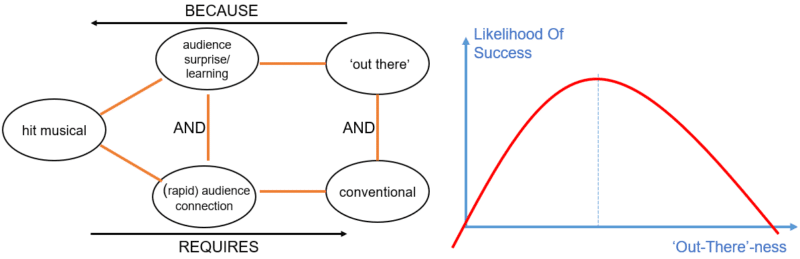

I just finished reading Albert-László Barabási’s book, The Formula (see review in next month’s SI ezine). The Formula is built around five Laws of success, each of which is cunningly illustrated through a cluster of mini-case study examples. Some of them contain contradictions. One of my favourites concerns the story of the 1945 musical, Carousel, a mid-century update of a failed 1909 play, Liliom, by Ferenc Molnar. In their bid to turn the failure into a success, songwriting duo, Rodgers & Hammerstein, seemed to have instinctively understood that a hit musical needed to comprise the right balance of familiarity and novelty in order to engage audiences. A contradiction that looks something like this:

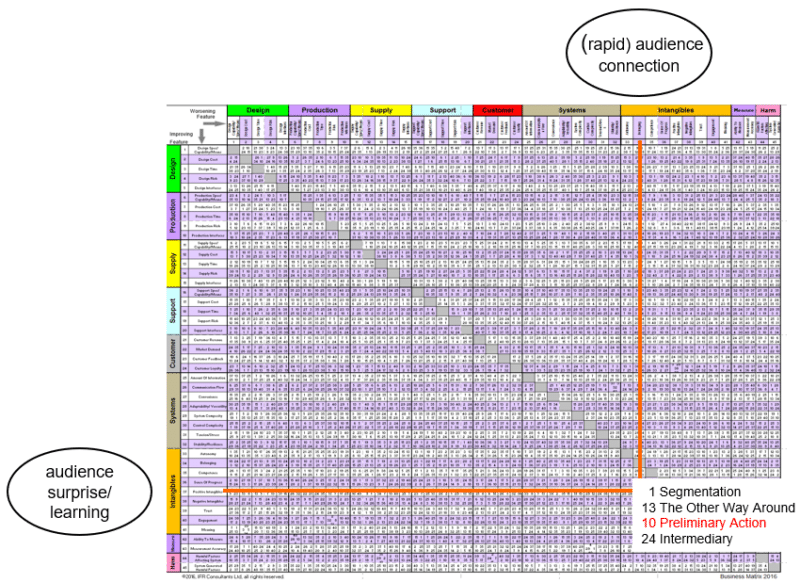

At a more detailed level, they also understood that one of the main difficulties with the romantic story-line is that the boy-meets-girl-boy-loses-girl-boy-gets-girl-back-again dynamic means the happy couple are only allowed to be happy at the end. Great for the purposes of having a big happy song to climax the show, but not so great in terms of making the audience have to wait before getting the ‘big number’. Ideally, the songwriters speculated, the audience got the thrill of the big romantic songs earlier in Act 1. The problem then being that, early in the story, the couple weren’t in love yet. Plus, of course, regular theatre go-ers, wouldn’t be expecting the big numbers at the beginning either. This is a bit of an odd one to map onto the Contradiction Matrix, but here’s how we might best map R&H’s dilemma:

The duo’s solution to the dilemma sounds totally obvious today: give the couple their first big romantic songs at the beginning of the show by having them singing about hoped-for love. I say obvious, because I think its fairly safe to say that just about every romantic musical since Carousel has performed pretty much the same contradiction-solving trick. Back in 1945, however, the elegant convention-break hit the peak of the ‘out-there’ Goldilocks Curve nigh on perfectly. In Matrix terms, Rodgers & Hammerstein did a Principle 10 on the convention-and-innovation challenge.

In 1999, Time magazine named Carousel the best musical of the Twentieth Century. Not bad for a Preliminary Action twist.