My stock answer when friends outside the UK ask me what on earth is happening inside the UK is either that I have no idea, or that the Government is deliberately creating a metaphorical forest-fire in order to clear out the non-metaphorical dead wood that, like all non-metaphorical dead wood stops the rest of the wood from thriving. Which one of the two I offer up depends on my prevailing level of contempt for the those purportedly in control and the latest act of lose-lose self-harm they just proudly launched.

For a long while now, my working theory has been that it doesn’t particularly matter whether I know what’s behind the ongoing shitshow-of-shitshows, my only job in life is to make sure the people I love and respect are antifragile enough to come out the other end stronger than we went in. And that the best way to achieve this is to do what anyone familiar with complex adaptive systems would do when the dial shifts to ‘chaos’ – try to make sure you learn faster than everyone else.

I realise neither my what or my how are good enough. And that both are made an awful lot easier to think through only when you understand the why.

That in turn means facing some difficult truths. It also means tracking back through history looking for examples of the Law of Unintended Consequences. AKA times when those in charge decided to break the fundamental first-principles of life.

So, when has that happened? Or, more pragmatically, when during the current UK society s-curve has that happened?

I think the first deviation from principle-based reality started in the 1970s. The economy was pretty bad for much of the decade. The slippery slope of post-WW2 decline was getting steeper. Something needed to be done. Enter Margaret Thatcher and her Government’s decision to switch from being an industrial nation to a ‘post-industrial’ one. Nothing wrong with this per se, but when making such a step-change, it’s usually a good idea to think about what kind of ‘post’ you’re aiming for. Given the prevailing urgency, however, Thatcher decided that the best shift to make was from an industry-based economy to one that was finance based. Deregulate the banks and become the banker (and insurer) for the world. In the short term this worked spectacularly well. Or at least it did if you were a banker. Things were less good if you were a miner. Or manufacturer. Or a person that did entropy-reducing creative work.

The fundamental principle-contravening problem with the world of finance is that it is a zero-sum game. Which, in the stark reality terms of the Second Law of Thermodynamcs means a slightly-worse-than-zero sum game. The act of moving money from one place to another place might create wealth for the person that works out a better place to send it than the next person, but in a complex world full of what are essentially one-eyed gamblers, it is only a matter of time before the 2nd Law will come and get you.

It probably took a decade of me-generation money-grabbing before the first of these inconvenient 2nd Law truths started to become apparent. Moving money around is largely frictionless so there’s nothing to wear out. In the real world, on the other hand, everything wears out eventually. Things like plumbing for example. Or power stations. Or the transport infrastructure.

Who was going to make sure all that stuff still worked? Maintenance and repair activities that meant people would have to get their hands dirty. Enter the next deviation from core principles. The right thing to have done was to ensure that the country maintained the requisite skills to keep the physical world working. Or, better yet, built the skills to design better, more efficient ways of keeping things working. This was the choice that recognised the vital importance of things like education, training and productivity improvement. The choice the UK Government took – ironically this time via Tony Blair’s (‘New’) Labour Government – was that education, training and productivity improvement was too expensive and that the best option for the UK was to import cheap, already-trained labour to do all the inconvenient, usually unpleasant, hard graft.

A big part of the failing of this lazy, again short-term, decision was a failure to recognise that there are two very different kinds of hard work. One kind of hard work – growing and preparing food, for example, or looking after the infirm and elderly – is highly meaningful, and the other kind – putting people on production lines expecting them to repeat the same monotonous action for eight-hours a day – is utterly meaningless. Or, put another way, soul-destroying. Once this distinction has been recognised, the first-principle imperative underpinning the desire for ‘productivity improvement’ is that ‘management’ works to either eliminate or automate all the meaningless jobs and properly rewards people (humans) for doing all the meaningful jobs.

Whether by plan or through abject failure to think, the UK decided to take the meaningless road. So now we live in a society that, by way of a vivid recent illustration, has seen a 50% decline in automatic car-washing machines and a 50% rise in the number of people that spend their working day washing cars. Worse, no-one in the automotive industry made any visible attempt to try and eliminate the problem by designing self-cleaning cars (perfectly possible if they had even contemplated the idea) – a solution we could’ve then sold to the rest of the world. Almost as bad, was the failure to recognise that, while cleaning cars is essentially a meaningless job for adults, it is actually quite meaningful when the task stays within the family. All my pocket-money when I was a kid came from cleaning my dad’s car on a Sunday. I hated every second of it. All it taught me was that if I did unpleasant jobs I would be given money. This, in retrospect, was the wrong lesson. The right one was that doing things as a family for the family (‘if the car is clean it will last longer and we can spend the money we save on a replacement on trips away’) helps build community and is therefore about as meaningful as things get.

Meanwhile, spool the clock forward another decade and all those convenient short-cuts begin to have consequences. Namely a population increasingly made up of one part lazy, untrained, entitled ‘nationals’ and another part an (sorry to have to use the phrase) underclass made up largely of hard-working ‘immigrants’. Enter Brexit. Otherwise known as the revenge of the former of these two groups. And now, for the last six years, another core principle of life is being contravened. This one’s a little more controversial, but essentially revolves around the question of globalisation, and how open or closed a nation is to people from outside. Whether or not you subscribe to the ignorant-racist Brexit-voter argument, what’s abundantly clear is that the UKs decision to make it more difficult for people to come into the country was the wrong one.

In a globalised world, small countries (and make no mistake, unlike 120 years ago, the UK is once again a small country) have no choice but to be more open than closed. In a globalised knowledge economy, the nation with the most productive brains wins. Nations with fewer brains don’t have the opportunity to be ‘world class’ at everything. They have to focus on what they’re uniquely good at, and trade the outcomes of that stuff for all the things they’re not good at. And as the world becomes progressively more interdependent, that need for trade in turn means that every innovation or change is inherently connected to everything else. The Covid-19 pandemic might have caused many governments to temporarily wonder about the wisdom of global trade, but nevertheless, every innovation these days is an ecosystem innovation.

Which then leaves the whole system somewhat stuck. The Government in a small room stuck between an 800lb gorilla and an elephant. On the one hand they ‘Got Brexit Done’ and gained election victory by telling everyone this was the case, and on the other, it has become abundantly clear to almost everyone that in the process of getting things ‘done’, they agreed to a whole suite of things that made life extremely difficult. Most pertinently, no more access to cheap labour on the one hand and no-one in the UK that wants to do the largely meaningless, unpleasant work that needs to get done on the other. The Government, three Prime Ministers later, is still unable to break out of the Get-Brexit-done lie. Now they find themselves in a vicious cycle of deceit and lies spinning so quickly that we’re forced to measure the half-life of our ‘leaders’ in weeks. With each new ‘famous for fifteen seconds’ egomaniac progressively less likely to admit the truth than their predecessor.

So where does that leave us?

First of all, hopefully, some learning for future generations:

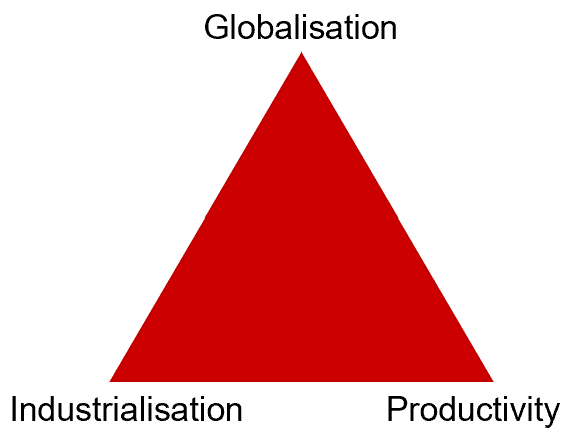

Break one core principle of life – favouring the short-term over the long term – and you’re in trouble.

Break a second – favouring easy-work over hard work – and you’re in trouble-squared.

Break a third – favouring meaningless work over the meaningful – and it’s trouble-cubed.

Break a fourth – favouring a closed economy over an open one – and a trouble-to-the-power-four exponential-storm is an inevitability.

Nothing will tangibly improve until all four of these fundamental errors are corrected. Exponential storms mean things will get exponentially worse. A lot of good wood will now – tragically – be destroyed along with the dead. Maybe this is when another principle finally kicks in – the so-called British ‘bulldog spirit’. Dunkirk. The Blitz. Etc. World War Two. Another time in history where utterly hopeless leadership created a disaster that only the collective will, blood and guts of the people kicked into action to repair the worst of the damage. On my good days I’d like to think that such a thing still exists, and that everything will come good again. On my bad days I think the same. The only difference between the two days is how low things go before we hit the bottom of the political barrel.

Expressed more generally, this fifth principle is one that tells us politics needs to be everyone’s business. It’s a principle that I and, I think, most people of my generation have been guilty of ignoring. Much as it might be tempting to distance oneself from the world of politics, the fact that so many British people did exactly that over the last fifty years, has now finally made us realise that if we ignore what’s important, we open the door for sociopaths, egomaniacs and criminals to step in. Nature abhors a vacuum and – as we now clearly see in the Houses of Parliament – will fill it with any old shit if we let it.

Break a fifth principle – favouring an apolitical life – and the four-principle driven perfect storm turns into a shitshow so big it will take some of us the rest of our lives to fix.

Oh well. What doesn’t kill us makes us stronger, I suppose. Call that the sixth principle in the societal set. Or maybe five and a half.