I visited my local bookshop this weekend. I noticed the Mindfulness section had grown since my last visit. Hmm. The next thing I noticed was the section’s expansion was largely accounted for by adult colouring books. In fact, about 80% of the total mindfulness shelf space seemed to have been allocated to colouring books. This doesn’t feel like good news to me. I’m sure it won’t be, either, to the mindfulness community.

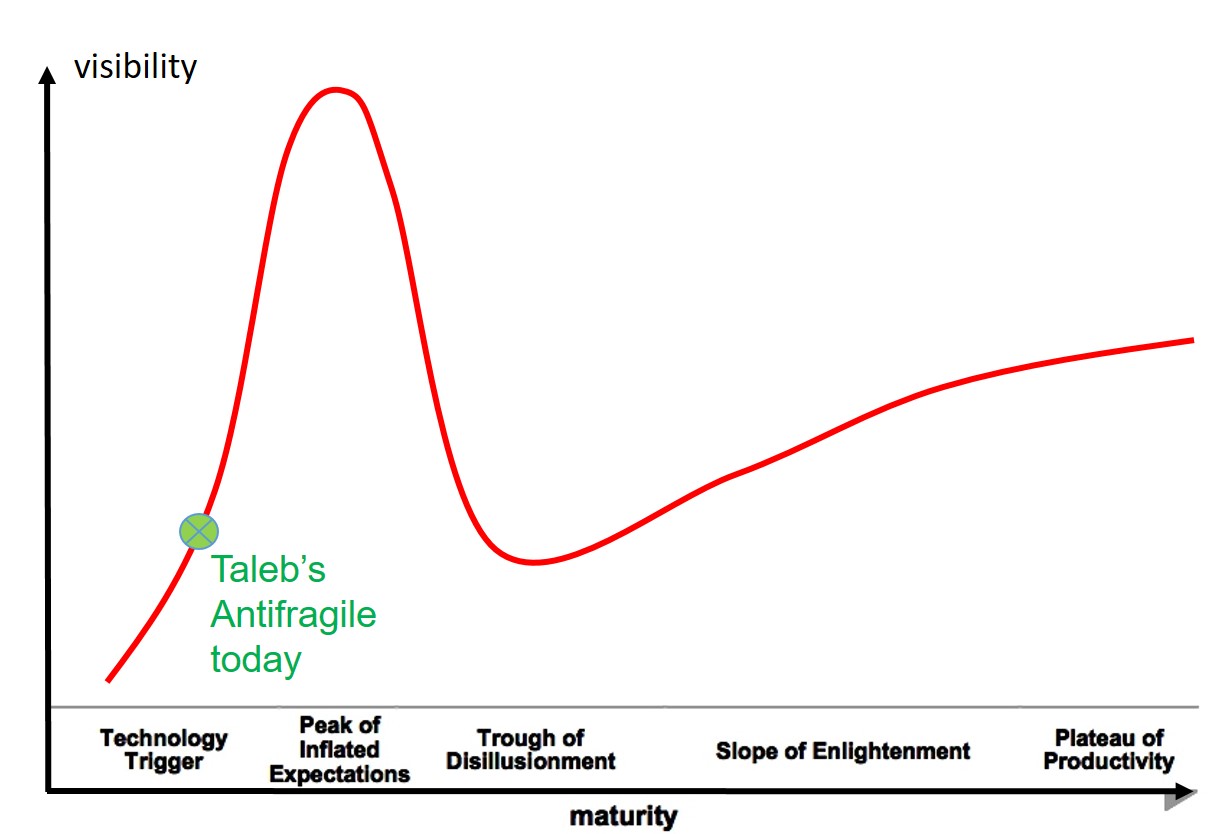

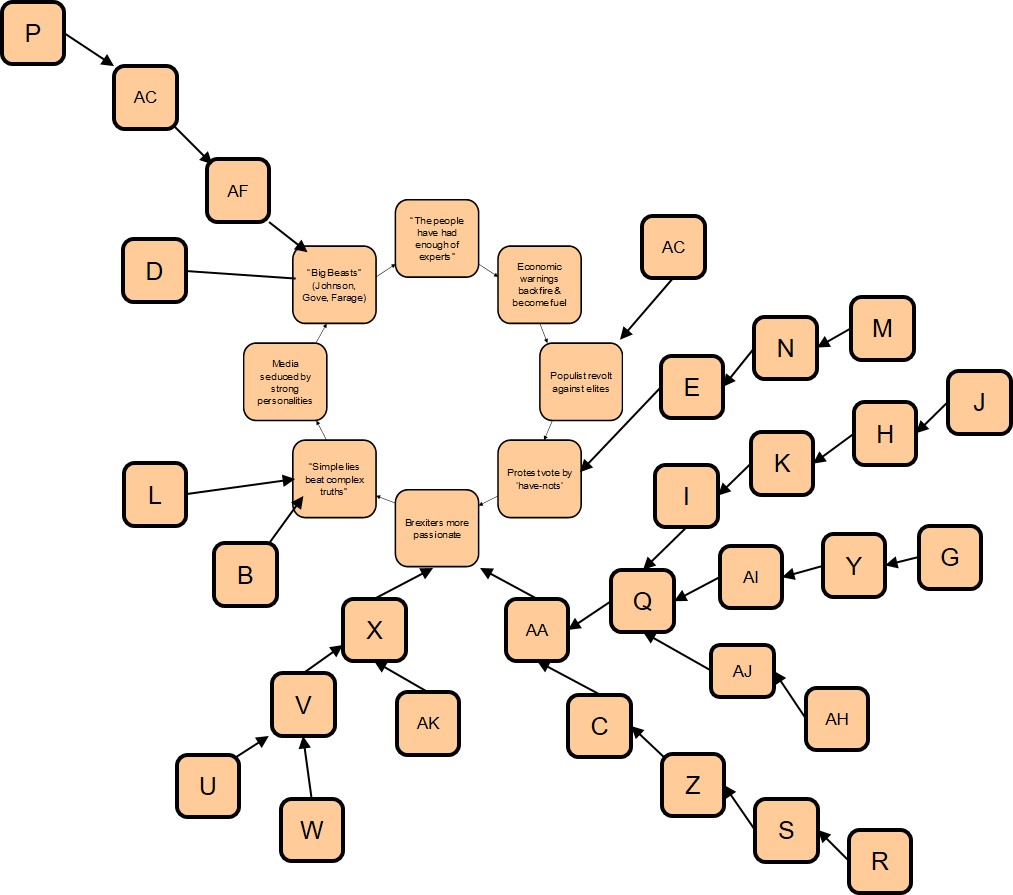

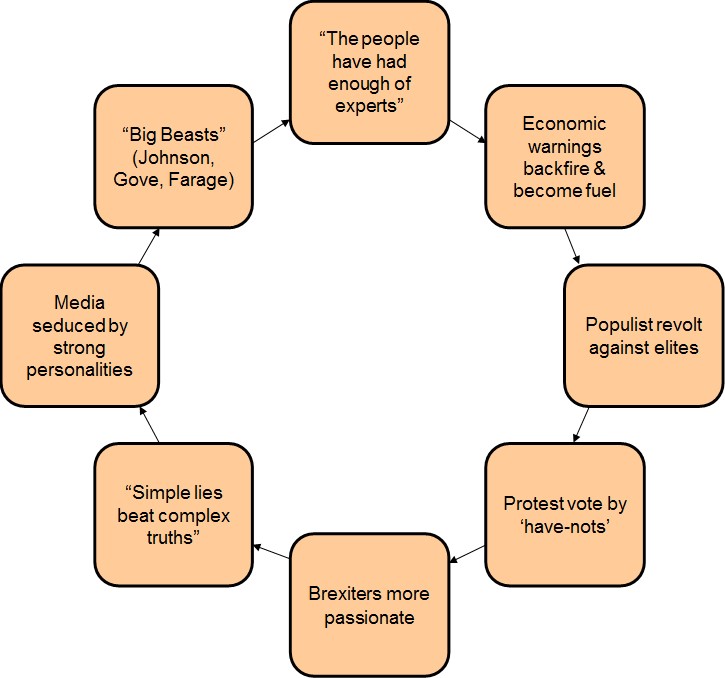

I know the devolution of any new idea to its lowest common denominator is a fact of life. The usual trajectory seems to go something like this. Someone announces a new idea to the world. If it’s any good, other people endorse it. These people don’t understand the idea quite so well, but they can see certain attractions. They recommend the idea to others, via these summarised attractions. More people pick up on the idea. They understand it even less, so they simplify it even further and, if they chose the right simplification, the idea goes viral. The idea originator is torn. On the one hand, they’re about to make a lot of money. On the other, the original idea has been reduced down to a meaningless catch phrase. The publisher says, don’t worry, use the money to set up an institute. Or maybe a university. Life is sweet. And nothing changes. No-one, in this case, is any more ‘mindful’, and societal stress levels have gone up and not down.

What I think is so startling these days is just how quickly this lowest common denominator tailspin kicks in. The whole of Devon, going by the shelf-space in my local bookshop, is colouring in pictures of enchanted forests. The line between mindful and mindless has become razor- thin in less than a year.

Forget the meaningful intent of ‘being mindful’, instead we now get colouring books. And a revisionist interpretation of ‘carpe diem’ that now tells everyone it means ‘enjoy the moment’. We literally couldn’t have travelled further from what the poet Horace originally meant. ‘Seize the day.’ As in, do as much as you can today, because you many not have the opportunity tomorrow.

The problem is that sounds like hard work. It was meant to be. Today, though, there seems to be a strong aversion to hard work. Life is stressful. I get that. Great to ‘live in the moment’ and colour-in butterflies for a couple of hours, but please don’t expect to feel better at the end of it. The bills still haven’t been paid, the kids have wasted yet another evening playing Mortal Kombat XL, and tomorrow’s school lunches still haven’t been made. Still, your stress levels are lower, right?

If they are, it’s a temporary phenomenon. That beautifully coloured picture of the enchanted forest proudly taped onto the fridge door is living testament to your increased fragility. Your decreased ability to cope. Your wilful blindness. Whenever we choose the easy option we make ourselves more vulnerable to the bad stuff real life throws at us. By extension, when we see broad swathes of society deciding to take the self same low road, we make the world an awful lot more fragile too.

Still, not to worry, eh, we’ve got National Colouring Book day to look forward to. August 2. Be there or be mindful.