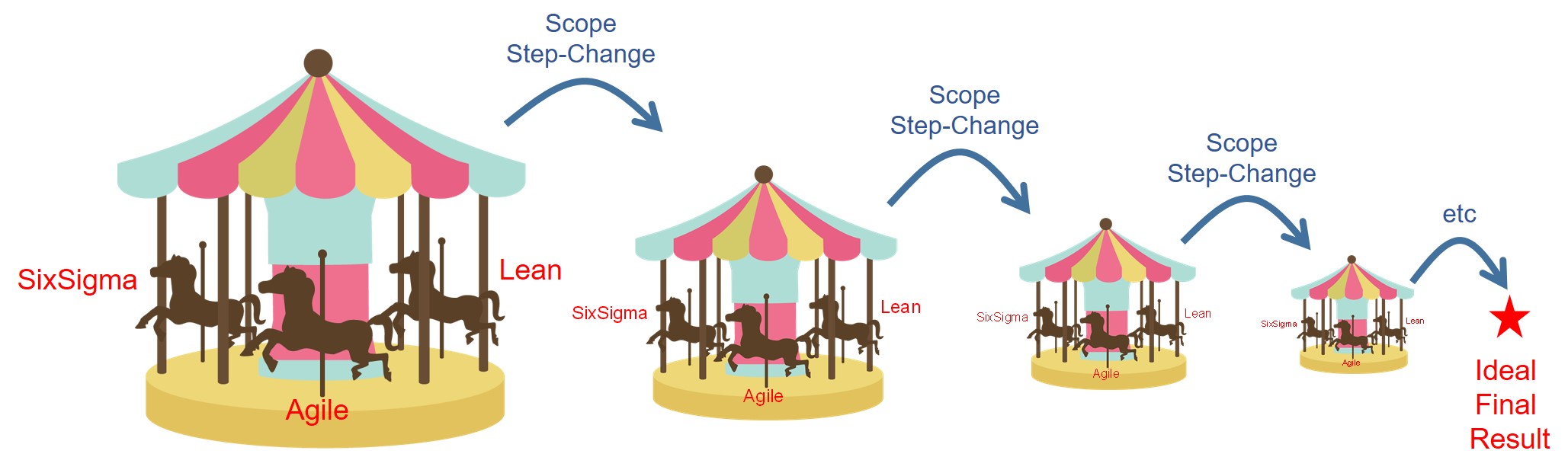

So, the big news at the Lean conference seems to have been Agile. Which is a bit depressing when you think about it. I guess these things have to take turns. A few years ago it was Six Sigma. I imagine, in a few more years’ time, the carousel will have gone full circle and we’ll be back at Lean again. If it wasn’t so depressing, you’d probably laugh.

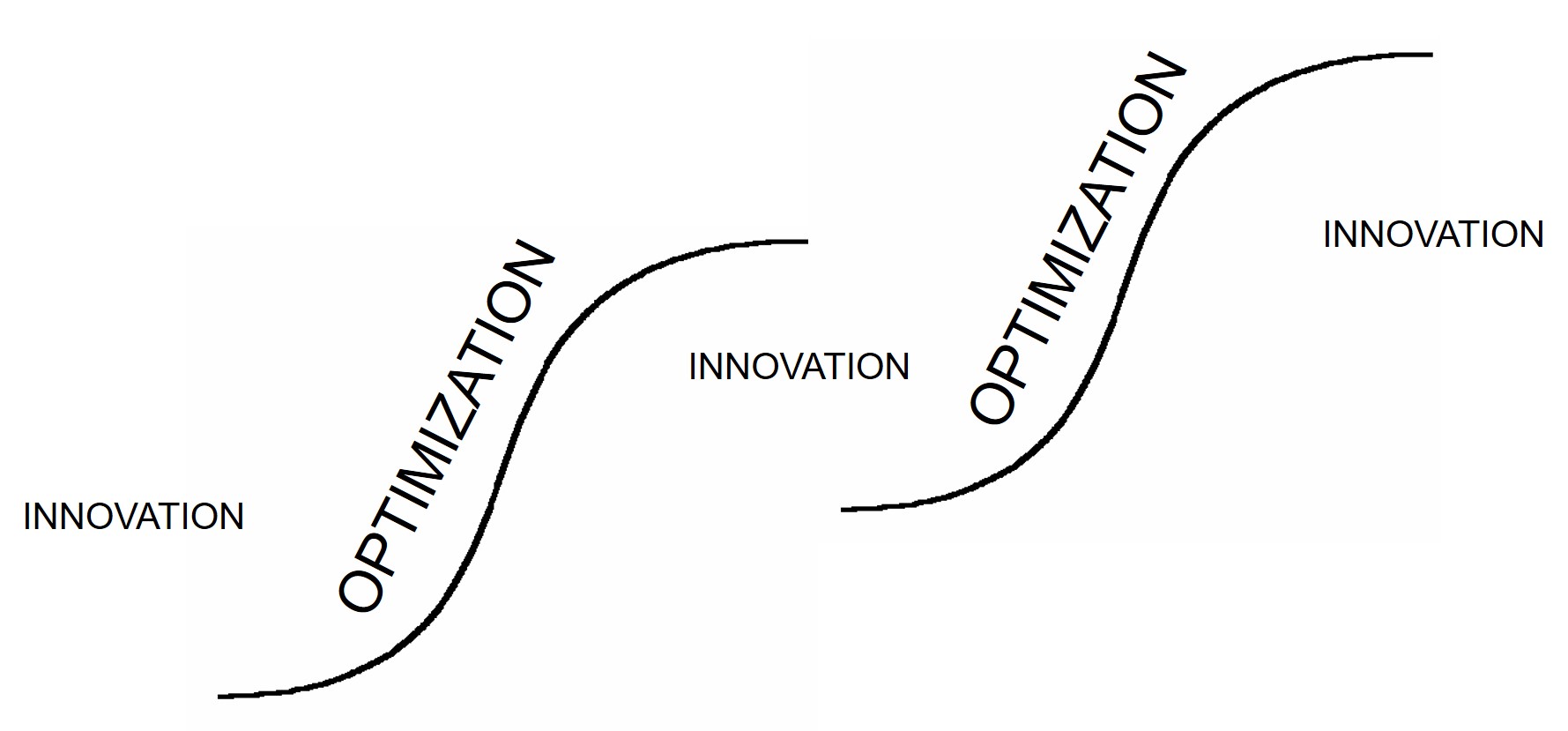

Someone asked the question, ‘has Lean innovated?’ I thought this was quite a good question. The answer didn’t appear to be immediately apparent. Clearly some Lean initiatives have delivered tangible benefit to the organisations that have deployed them. But is the benefit coming from step-changes to the Lean methodology or merely optimization of what’s been there from the first time Taiichi Ohno devised a better way to organise Toyota’s production systems?

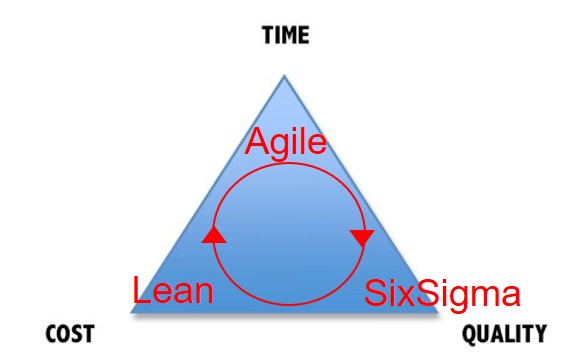

It began to sound like a contradiction. Innovation or optimization? Or innovation and optimization? The more I thought about it, the more the resolution looked like a story of hierarchical separation. At the tool level, Lean has made several step changes. At the governing-principle level, I don’t think it has. The pillars of Lean have not changed over the years. Lean practitioners have, at best, optimized their understanding of these pillars. No doubt derailed along the way by diversions to investigate Six Sigma. And more recently, it now seems, via Agile.

Maybe the integration of the three is the innovation?

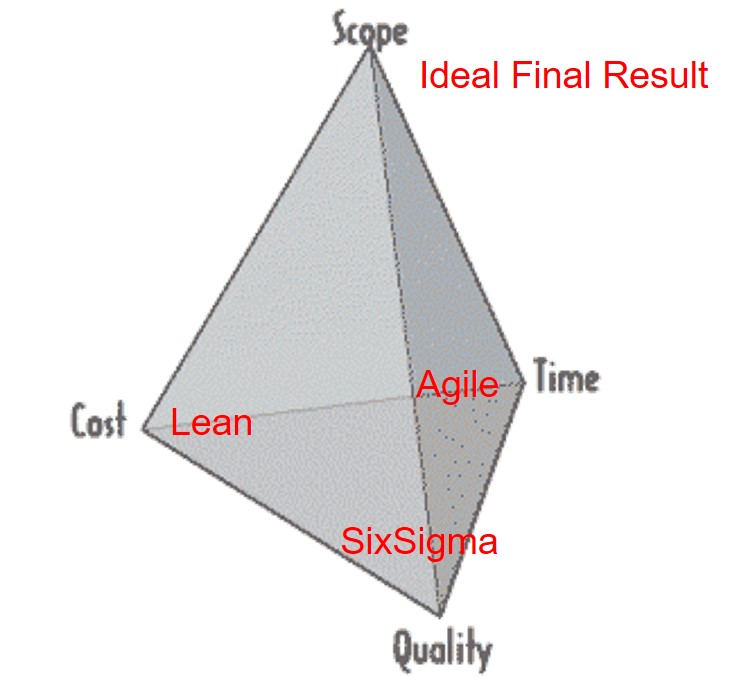

Sadly, if we look at the Iron Triangle of business, all Lean, SixSigma and Agile are really doing is shifting the emphasis between Cost, Quality and Speed. It’s still the same old same old: cost, quality, speed – choose any two you like… “everything was taking too long… so we went Agile… then we realised we were just doing the wrong things faster… which made us a bit confused so we brought in the Six Sigma Black Belts… which took out some of the variation… but that didn’t make the customer any happier…” and, hey presto, the carousel has come full circle again.

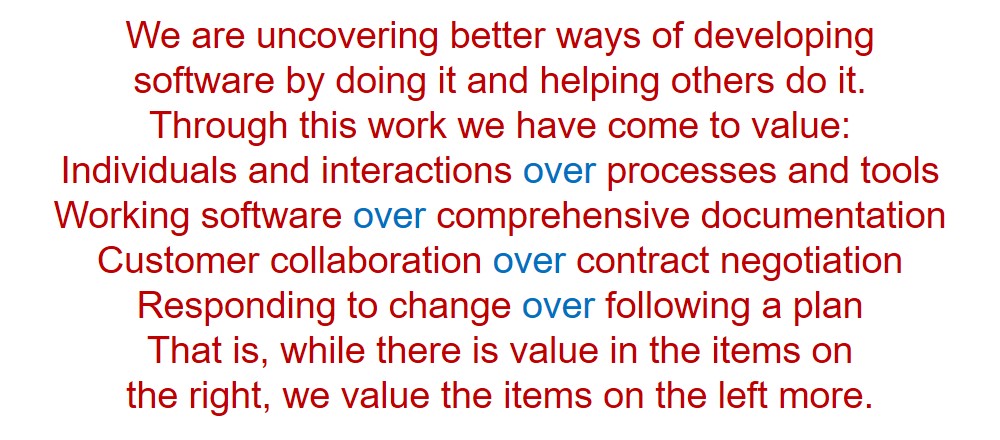

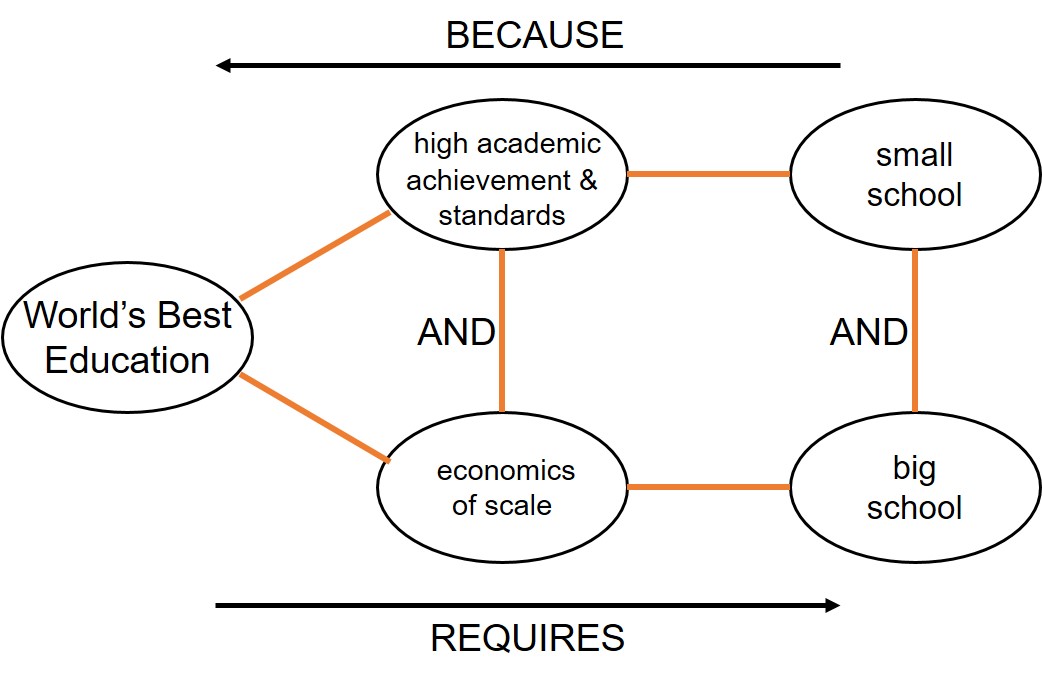

Should companies use Lean? Should they go Agile? Should they use SixSigma? Should they use Lean and Agile? All three? They’re all meaningless questions, because they’re all just causing the same stupid carousel to spin faster and faster. All three are fundamentally based on an erroneous assumption that life is full of inherent trade-offs. We can see it most vividly in the Agile Manifesto:

‘Over‘? What are you talking about? What these lines effectively say is, ‘there is a trade-off between X and Y, and we’re biased in the direction of X. Granted, it’s a choice, and sometimes choices are good. But rarely is this so if the initial question was a dumb one. Why can’t I have individuals and processes? Why can’t I have responsiveness and a plan?

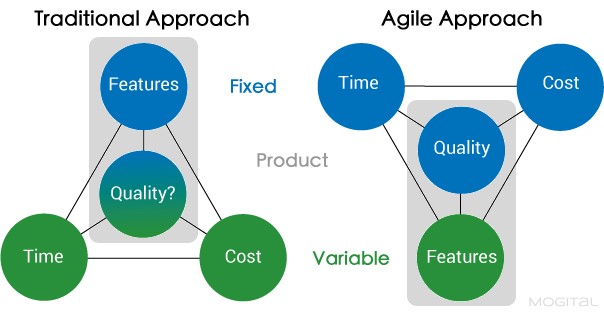

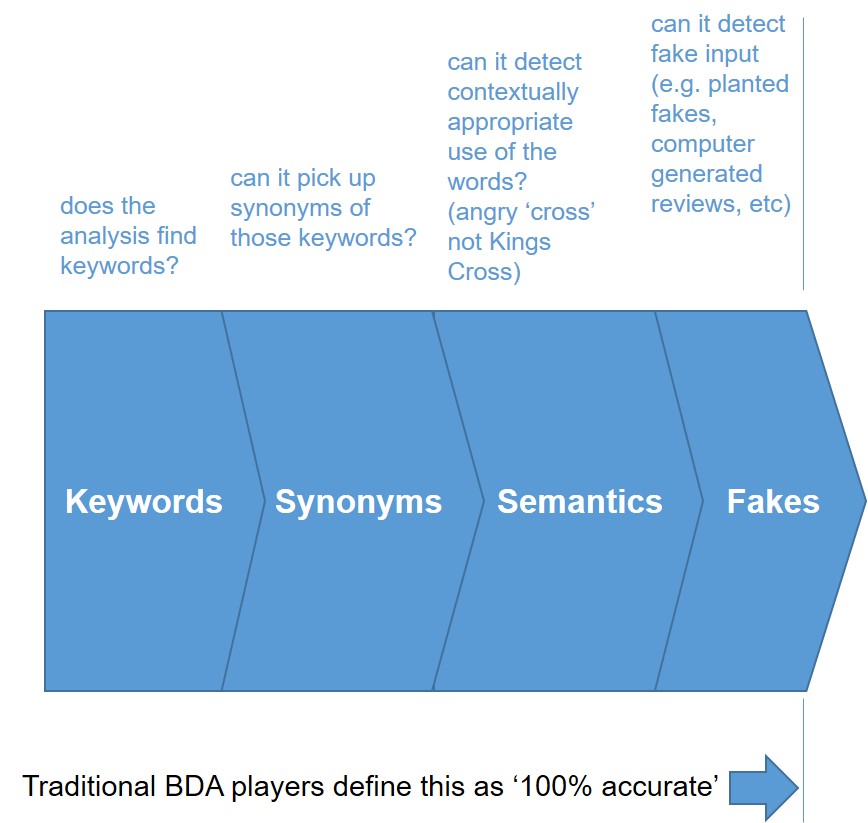

In fairness to the Agile world, they do at least acknowledge that the Quality-Cost-Speed carousel stops being fun after a few spins. Coming from the high revolutions per minute world of software development, Agile practitioners have realised faster than most that the iron triangle actually has a fourth side: Scope.

Adding Scope to the carousel ride ought to be a good idea. But, sadly, not if – as the Agile practitioners have done – you just use it as another trade-off parameter. Here’s how the Agile community describes their four-sided carousel ride:

Essentially this picture reads: let’s stop fixing Scope and oscillating between over-budget, late and inadequate quality, and instead let’s fix those attributes and let the Scope be the thing that varies. Huh?

Again the wrong question. It’s not a trade-off. You just have to put yourself in the position of the customer to know that. The customer doesn’t want a ‘perm any three from four’ compromise. They want you to solve the contradictions and ‘get better’. Something like this:

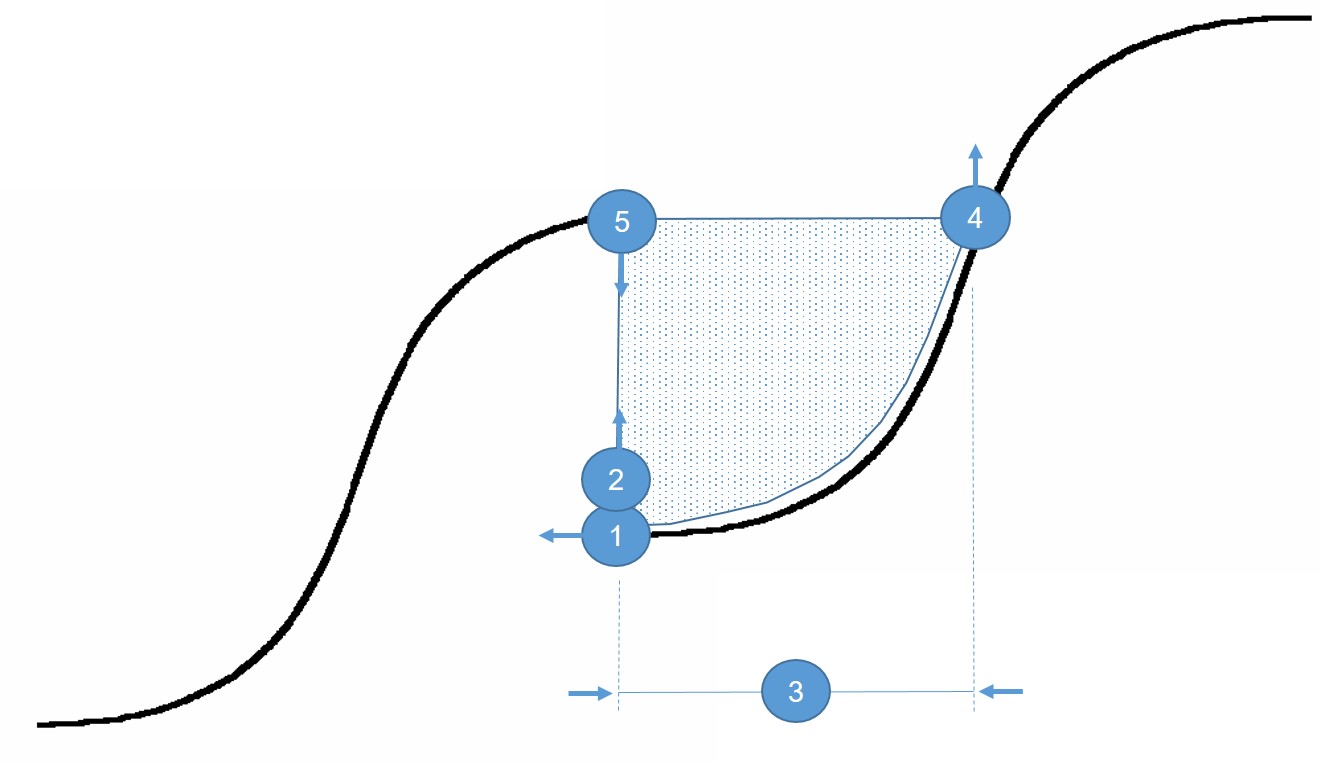

Including ‘Scope’ on the carousel ride allows us to recognise that successful evolution has a direction. Everything evolves towards an Ideal Final Result end state in which all of the desire customer benefits get delivered ‘free, perfect and now’.

The way the world works is that we only step closer to that evolutionary end goal when we reveal and resolve contradictions. The only reliable method for doing that is TRIZ.

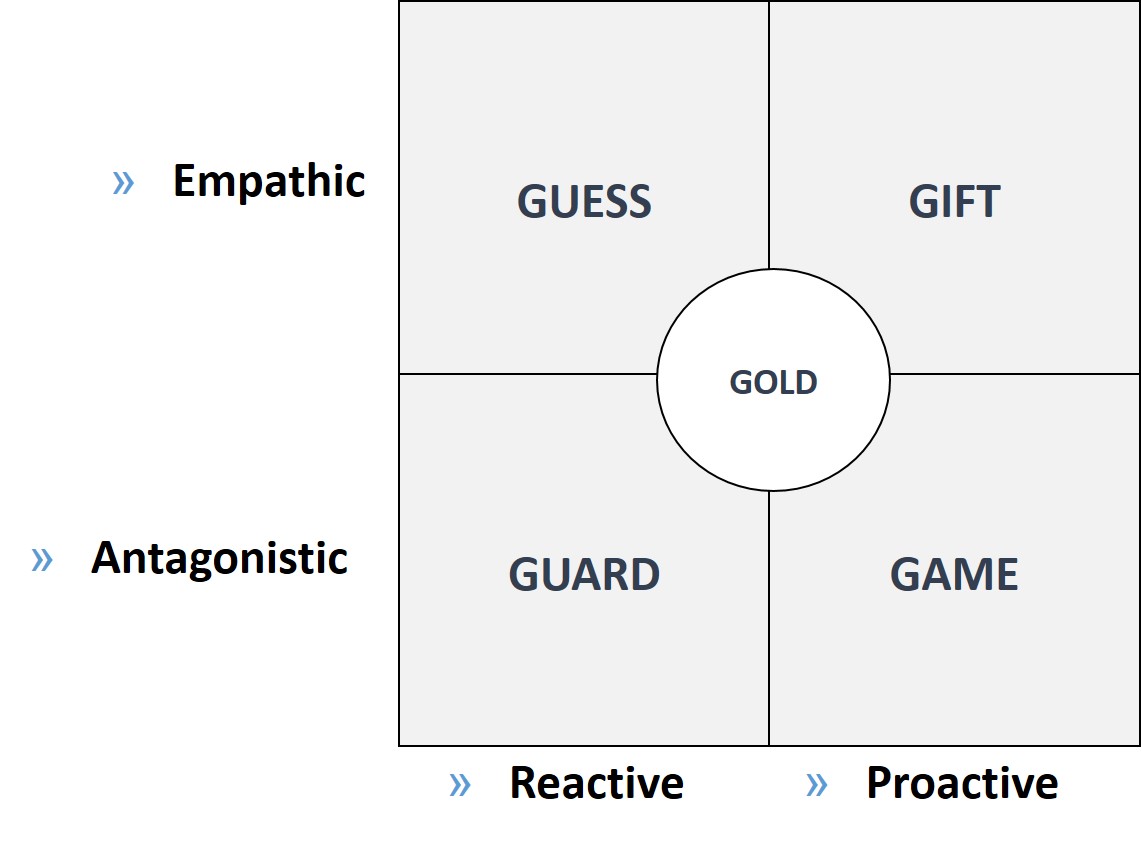

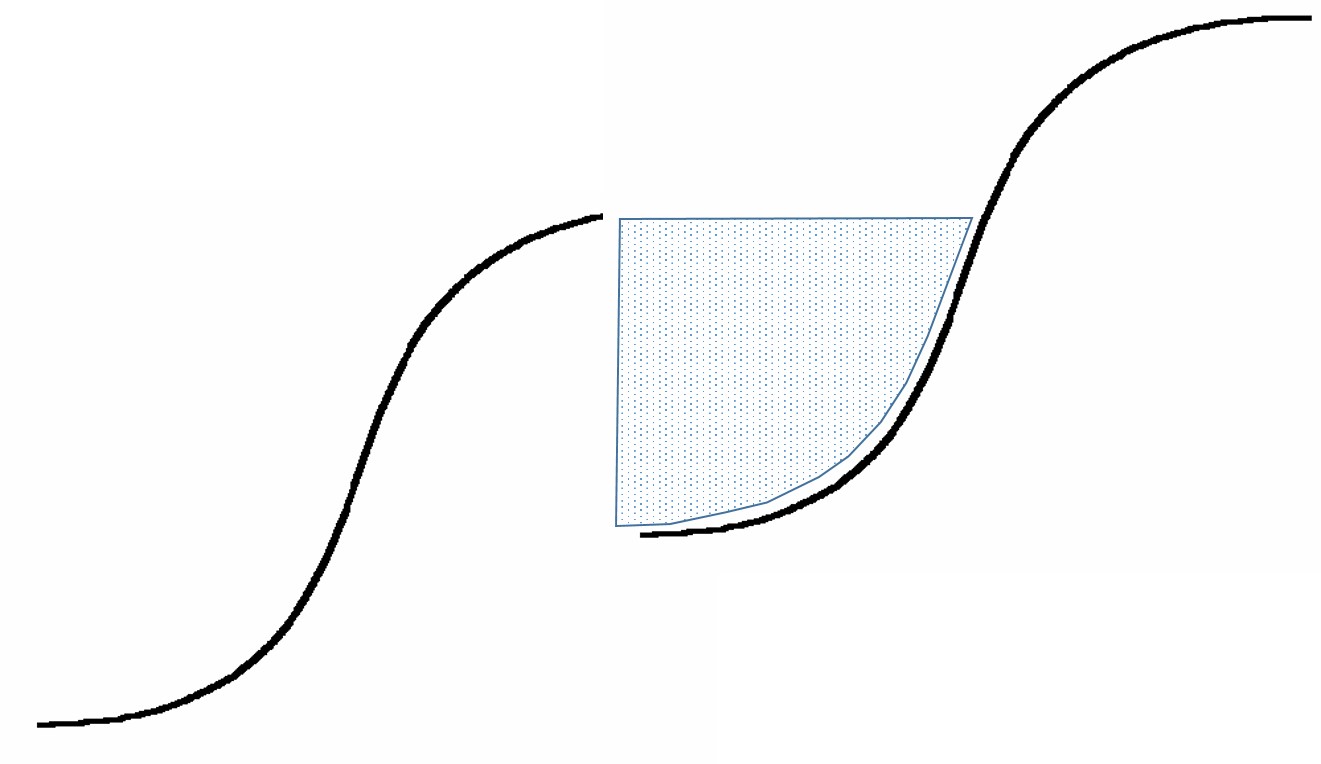

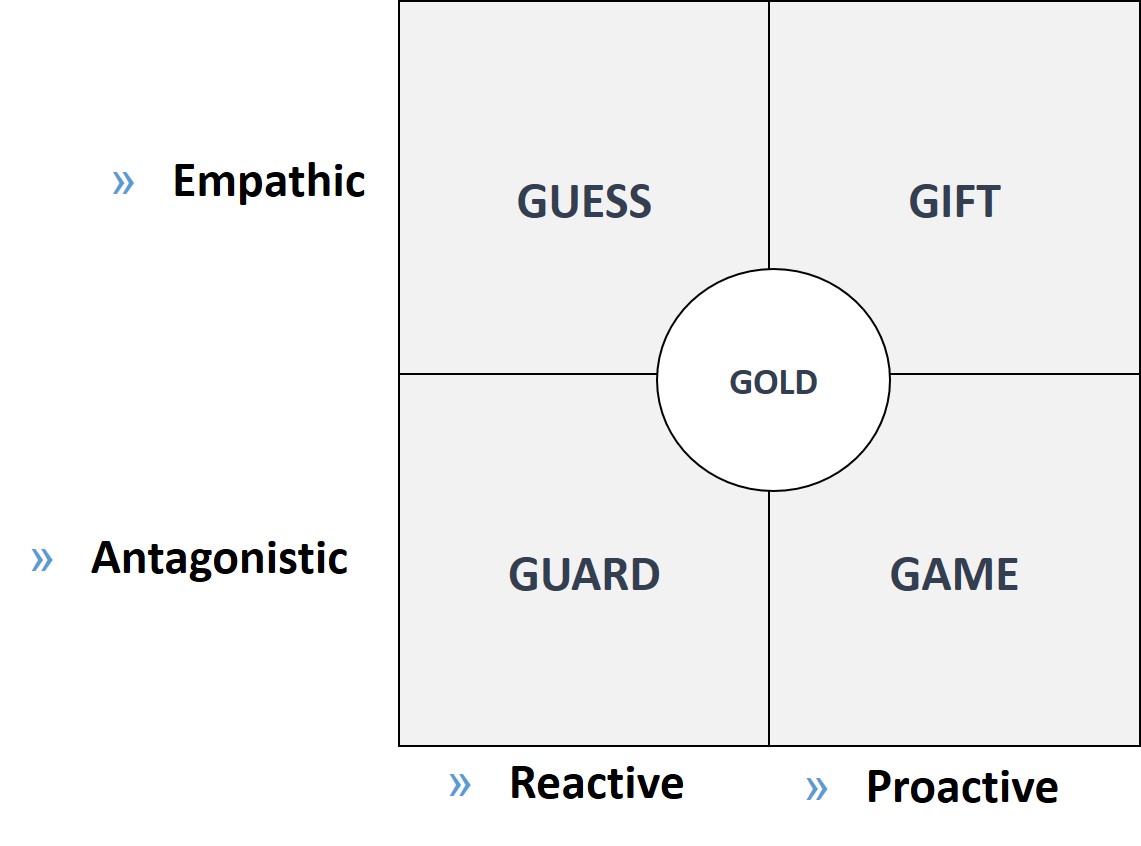

Lean, Agile and SixSigma have a role in life solely as optimization tools. The right blend of those tools then depends on the relative importance of Cost, Speed and Quality at any given moment in time. When people on the optimization carousel start to feel queasy, it’s probably a sign that there’s a need to solve a contradiction and make a jump to a better carousel. Something like this maybe:

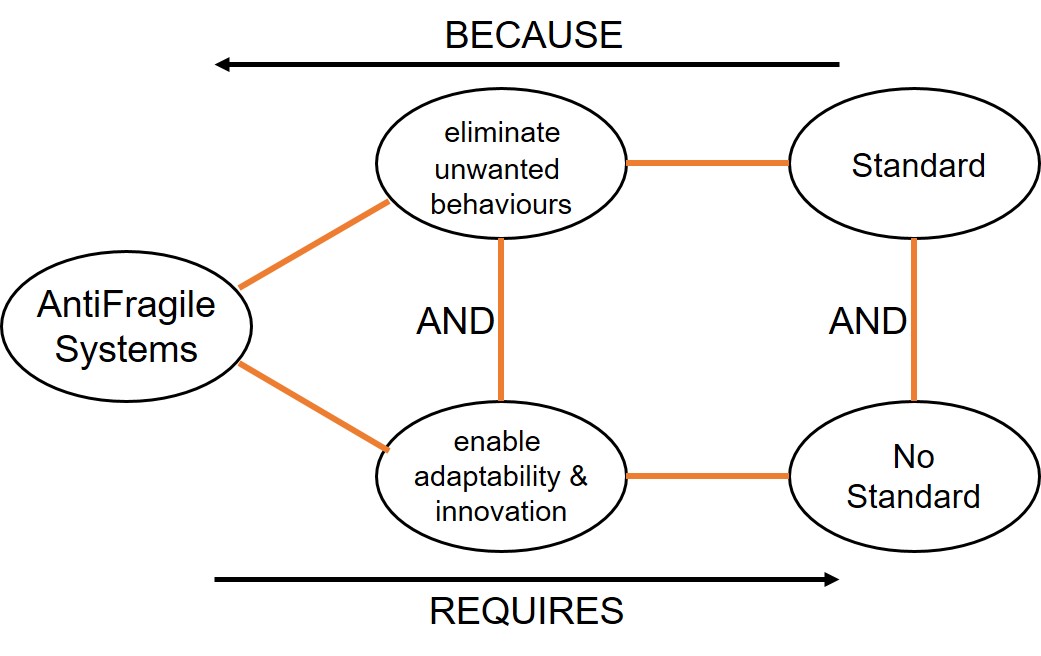

I wish this could be the end of the discussion. Sadly, I suspect it won’t be, and before too long we’ll start seeing Lean-Agile-SixSigma education programmes. As if this is some new kind of panacea. And then we’ll get Certification. And then Standards. And before we know it, the whole optimization carousel will fly off its axis and spin into futile oblivion. Still, I suppose it keeps everyone from having to deal with the real issues. Like giving customers what they might actually want.