It might have been coincidence. Or it might not. Yesterday I received my copy of the Nassim Nicholas Taleb foreworded version of Carlo Cipolla’s mini-classic, ‘The Basic Laws Of Human Stupidity’. And yesterday, the UK Parliament decided that the country would have a general election on December 12.

The will-they-won’t-they election decision has been debated for several weeks now. The Conservatives have been nervous because Boris Johnson promised – on his die-in-a-ditch life – that the UK would leave the EU on 31 October and now we know he has failed, there is likely to be a backlash. Picture Nigel Farage rubbing his grubby-hands with glee at the upcoming advertising campaign. On the other side of the house, the Labour party have been trying to put off the election for as long as possible because they’re about 14 points behind in the polls thanks in no small part to the fact that, in Jeremy Corbyn, they have a leader that appears almost totally un-electable by anyone other than a devout Marxist. The Liberals, being the liberal wimps they are, seem relieved that the election decision gave them a get-out-of-jail-free card in terms of failing to stop Brexit from happening. Thanks to the first-past-the-post election system, they will win a few more seats and, better yet, when the dust settles, get to shrug their shoulders and say they did the best a small party could do in the circumstances. The Scottish Nationalist Party, meanwhile, are rubbing their hands with glee at the prospect they will wipe out the Conservative Party in Scotland, and lay the foundations of another independence referendum that, this time around, thanks to Brexit, they will likely win. The SNP will thus, in their minds, do a good thing for Scotland, but in reality will end up making themselves and the rest of the UK worse off. Which, finally, leaves the DUP, who have swiftly sunk back to their pre-2017 level of irrelevance outside the Unionist community of Northern Ireland. The election decision means they no longer have any of the very non-linear power they’ve held since the Conservatives were forced to buy them off after the 2017 election. One day they decide for the nation; the next, no-one gives a damn what they think any more. It’s a tough game, politics.

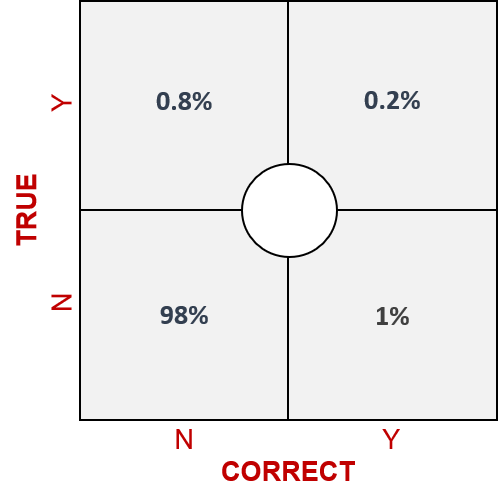

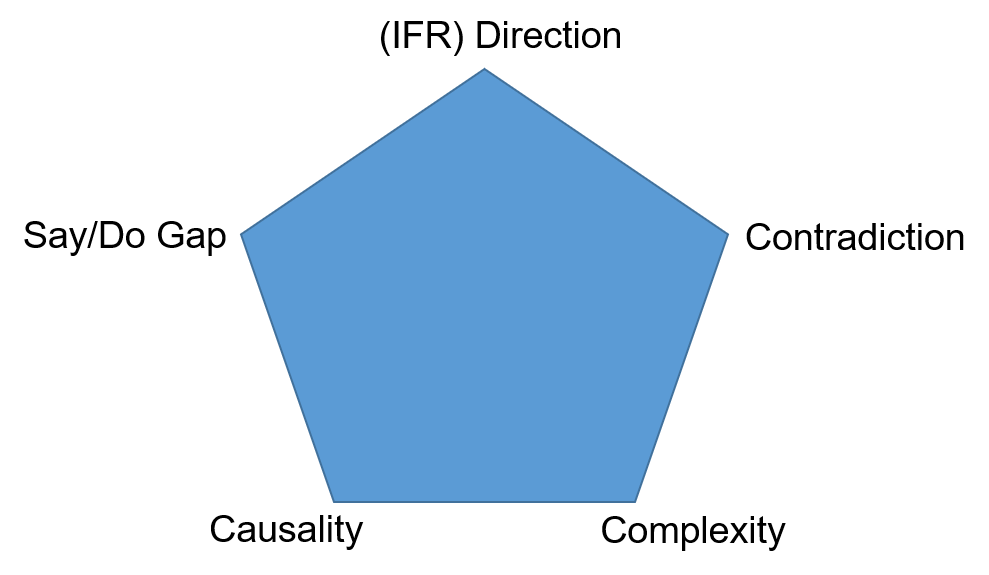

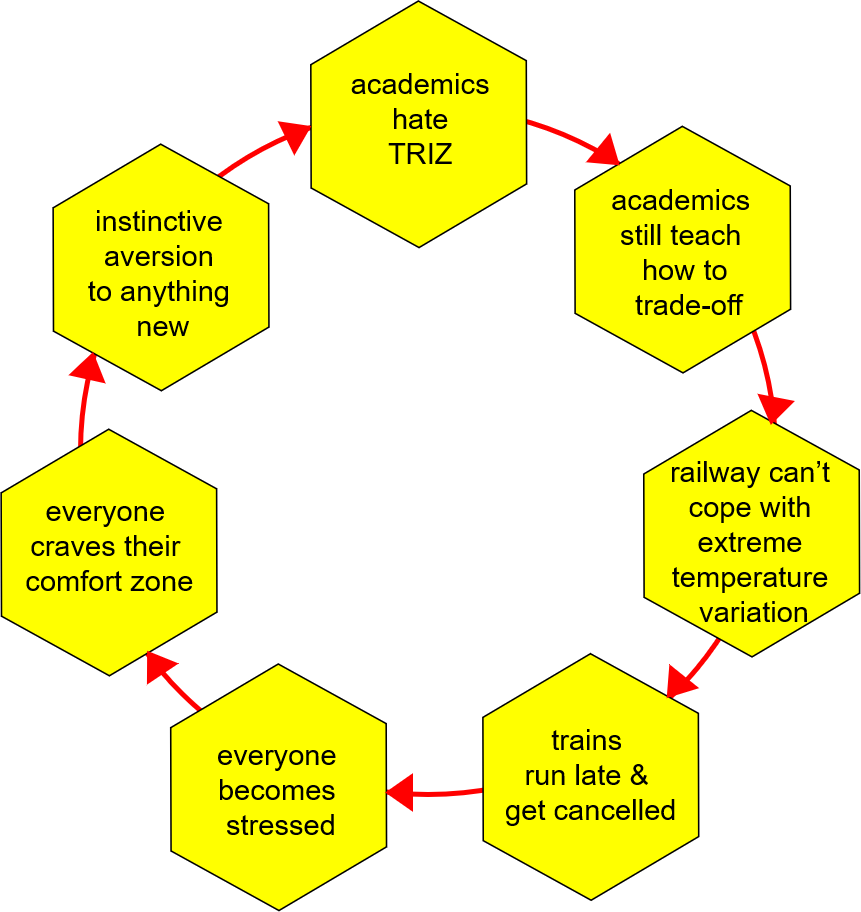

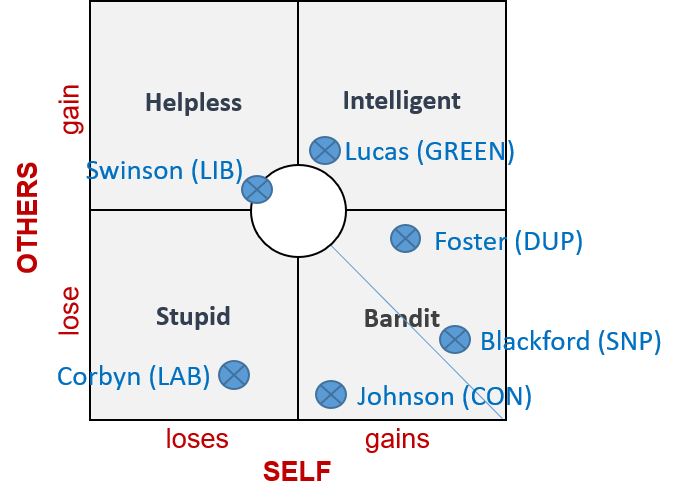

Plot this sorry mess onto Cipolla’s Map Of Stupidity and the UK political scene currently looks like this:

The Conservatives get to be the win-lose Stupid Bandits; the SNP and DUP get to be intelligent Bandits; Labour look like they’ve just sleep-walked into the Boris Johnson Bandits trap and, thanks to Jeremy Corbyn’s lack of leadership prowess, get to play the plain Stupid role in proceedings. Jo Swinson’s Liberal Party continue in their Helpless role – ‘winning’ a few seats while losing the prize they could’ve had. Which leaves Caroline Lucas and the Green Party as the only vaguely ‘intelligent’ players in the game. They too will likely win more votes and, who knows, even one or two extra parliamentary seats, and might even help build some more Save-the-Planet momentum. But, of course, will largely have no impact on the Brexit state of play at all.

All in all, the omens are not good for a meaningful outcome on December 13. Labour and Conservatives are already playing to their Stupid and Bandit types and are trying to make the election about more than just Brexit. But with Brexit in its current unfinished business state, the election can be about nothing else. And here, then, is the real problem. Anyone that voted Remain in the EU referendum is basically dis-enfranchised right now. The Conservatives want (hard) Brexit. The Brexit Party will push them to go even harder. Labour, in theory, are standing on the idea of a confirmatory referendum, but everyone knows that Corbyn doesn’t believe in the idea, and as a consequence he’s trusted almost as little as Johnson. The Liberals have chickened out. The Greens offer little more than a protest vote. Leaving only the SNP offering a meaningful home for Remain voters. Nice if you live in Scotland, not so good for everyone else. Unless they start fielding candidates in the rest of the UK.

As the last three years have shown, almost any kind of worst-case scenario imaginable proves to be inadequate within short order in Brexit Britain. The half-life of British political Truth is now measurable in hours and minutes. Meaning that predictions of what will happen are little better than a coin toss. Especially, too, in light of the fact that there’s the Facebook-broke-democracy element still to take into account. This election, in other words, takes place in an environment in which every party now understands that Facebook and other social media channels offer a non-legislatable, largely illegal Wild-West in which quite literally anything goes. Lying politicians has always been an oxymoron. Today, thanks to Facebook, they get to customize those lies to target the weak, the vulnerable, and the racist. Except, if I read Cipolla’s Stupidity Map right, I believe a prediction saying things will continue to get worse is very likely to be right. Which, to my mind, means December 13 (a Friday – surprise!) will bring the UK another hung parliament on December 13. This will then be followed by yet another extension begging letter to the EU by the middle of January. This will then prolong the agnoy for several more months until, finally, in utter despair, enough careerist politicians will stick their head above the political parapet and tentatively suggest what has always been the only sensible way through this mess, another referendum. This will then result in a revocation of Article 50, and the UK can safely return to its (comparatively) blissful 2015 state. Only several hundred billion pounds poorer thanks to the five years of combined political Banditry and Stupidity.

Wake me up in 2021.