Ever wondered why the world is full of cracked paving stones?

I finally worked it out. A couple of years ago, I had someone come and lay a paved path outside my house. I watched the process as it progressed. I also asked the people doing the job why it was that there were so many cracked paving stones in the world. ‘Bad construction’ was the gist of their reply. Which I took at the time to mean, ‘cowboy builders, at the opposite end of the construction industry spectrum to us’.

But – of course – here we are two years later and several of my non-cowboy fitted paving stones are cracked.

Having watched the installation process, and now seen that it’s pretty much the same process you’ll read about on any of the thousand plus online tutorials, the likelihood or otherwise that a person will end up with cracked paving slabs outside their house has virtually no correlation with the skill or lack of skill of the builder, but rather the fact that the whole premise of how paving slabs are laid is dumb.

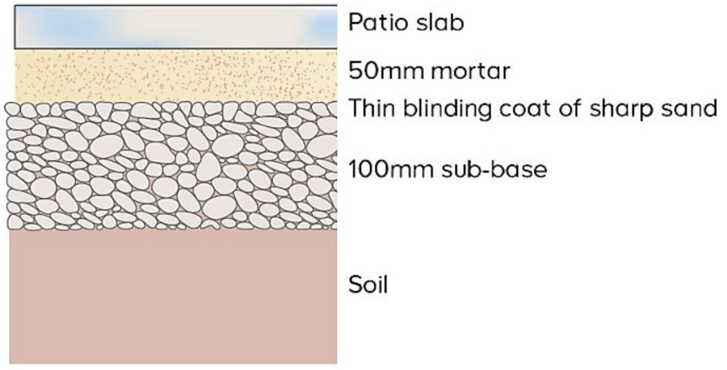

That premise starts with an assumption that the earth under the slab, the mortar that sits below the slab, and the sub-base that sits below the mortar doesn’t move. This is pretty much the same assumption used when roads get built and the track for railways gets laid. The only difference being the thickness and type of the sub-base layers.

This feels to me a bit like builder version of King Canute. That, by drawing a line in the metaphorical and actual sand, they might order the tide not to come in. In the fight between regal dictat and Mother Earth, however, Mother Earth wins approximately 100 times out of 100.

One of the principle characteristics of the Earth is that it moves. (A geologist friend once tried to amaze me with the ‘interesting’ (his word) factoid that the Earth’s crust has the same basic strength, stiffness and viscosity properties as toothpaste).

This being the case, one would have expected that someone by now might have worked out how to design structures that remained stable despite the fact that the ground they were built upon was moving. Sure enough, lots of people have solved this problem. They just never told the paving slab industry. Or the people that sell beautifully sieved ballast to hold railway sleepers in place. If such discussions had taken place, the railway ballast experts would have realised that what they’ve created is just about the worst possible ballast stone size profile. And paving slabs and the bases that sit under them wouldn’t keep looking like they have done for the last n-thousand years.

None of this is rocket science. Rather it’s a little bit of zero-cost geometric cunning. Something I’m in the process of integrating into my replacement paved path. Something I’m also pretty certain the path-laying, road-constructing, railtrack-laying industries have no interest in at all. After all, if paving stones didn’t crack every couple of years, if potholes didn’t appear in our roads every winter and if rail crews didn’t have to make daily checks on the integrity of the track, they’d run out of work for everyone within a year. And who’d want that?