One of the natural tendencies of the world is expansion beyond our core skill set. We are, to quote one of my favourite bands, ‘gluttons for our doom’ when it comes to our collective inability to say ‘enough’.

I see the problem a lot in the world of problem solving method developers. My first hands-on experience was with Axiomatic Design creator, and arrogant nut-job, Professor Nam Suh about a decade ago. Although massively over-complicated (I suspect to justify the blushingly-high consulting bills), when push comes to shove, the ‘axioms’, while they’re not actually Axiomatic, do provide some useful direction to designers in some situations. Then, no doubt, because once you start getting used to being paid blushingly high consulting fees, it becomes kind of addictive, so that when the fees start to dry up, its common to feel a need to broaden your horizons. And so Professor Suh, sensing that the innovation world was looking like a big opportunity, decided to start telling the world that Axiomatic Design was an innovation panacea. He persevered for a couple of years.

It took that long for the world to work out that Axiomatic Design was about as useful for the innovation job as digging a swimming pool with a plastic teaspoon, because when you’re methodology includes matrix algebra, it can very easily hypnotise people into believing you. Especially if they themselves don’t know what matrix algebra is. Fortunately, the world has now cottoned on to the idea that not only does matrix algebra have nothing at all to do with innovation, neither does any kind of mathematics. Innovation is pretty much all about putting the mathematics on one side until you’ve finished doing the innovation part.

Anyway, before I go off on too big a tangent, it seems we’re seeing the rise of ‘Lean Design’ as the latest output of a community of smart people that have hit the limits of their capabilities and are feeling the need to expand into new domains.

No-one in the Lean community can even define ‘lean’ it seems to me, so when I’ve been quizzing leading lights about the meaning of ‘Lean Design’ I get even less clarity.

I hear the phrase, ‘the designer casts the biggest shadow’ phrase a lot, but when I nod and respond with a ‘so what? or ‘and then what?’ question all I seem to get in response is something along the lines, ‘yes, but the designer casts the bigger shadow.’

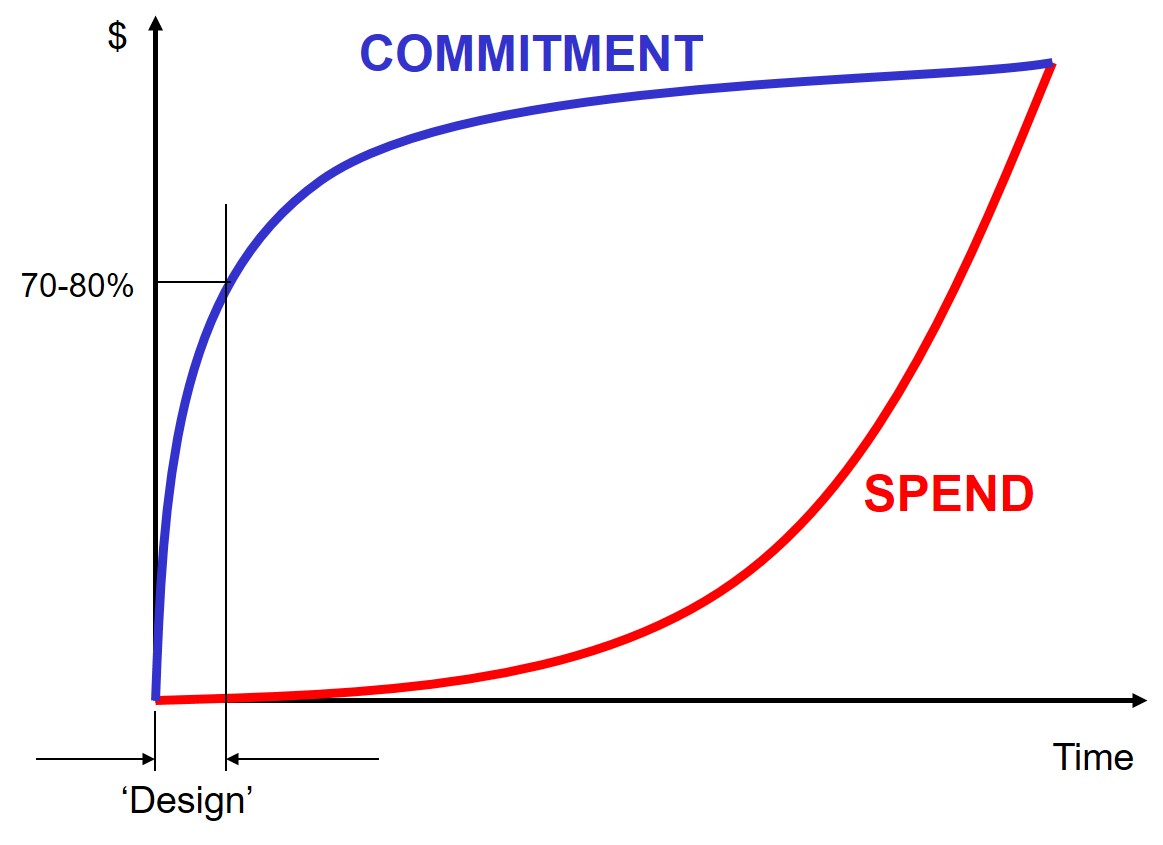

I know. It was drummed into my head from the first day of my first real job in the aerospace industry. A design project, it turns out, where my back-of-cigarette-packet design calculations transformed themselves, within a year, into about £20M worth of overall project cost. This is the picture we used to convince ourselves that we should make sure we were using the very best cigarette packets to do our calculations on:

To me, ‘lean design’ is all about recognising and managing this massive hysteresis between the designers spend and the commitment that spend imposes on what happens after they finish.

And, to be as clear as I can, that management job had and still has absolutely nothing to do with the world of Lean.

‘Lean Design’ seems to be borne of a handful of ‘Lean experts’ that have traced back some of the ‘waste’ they’ve been told to go look for and found themselves in the Design department.

Sadly for all concerned – the Lean experts, the Designers and the poor project managers faced with the thankless task of making sense of what the experts and designers try and tell them – just because its possible to trace some apparent ‘waste’ back to a source, doesn’t mean that source is any kind of root cause.

The root cause is there is no root cause. Not in a complex environment. And Design is fundamentally about dealing with complexity. Complex environments require different ways of operating. Different, that is, from all of the ways that the Lean world currently thinks the world works.

Reducing the overall cost of projects is a fine and noble ambition. You only have to see £20M disappear in a puff of smoke (quite literally, the day I exploded a jet-engine – fortunately not on that first project) to really understand the value of taking as much care to do the best job you possibly can during the design process. But in a complex environment, you realise too that, no matter how good your calculations are, there’s a whole bunch of stuff you don’t and can’t know yet. You have to try stuff out, learn from it, and make sure you operate in such a way that you’re always, at every moment, looking to spend the least amount of money to answer the greatest number of unknowns.

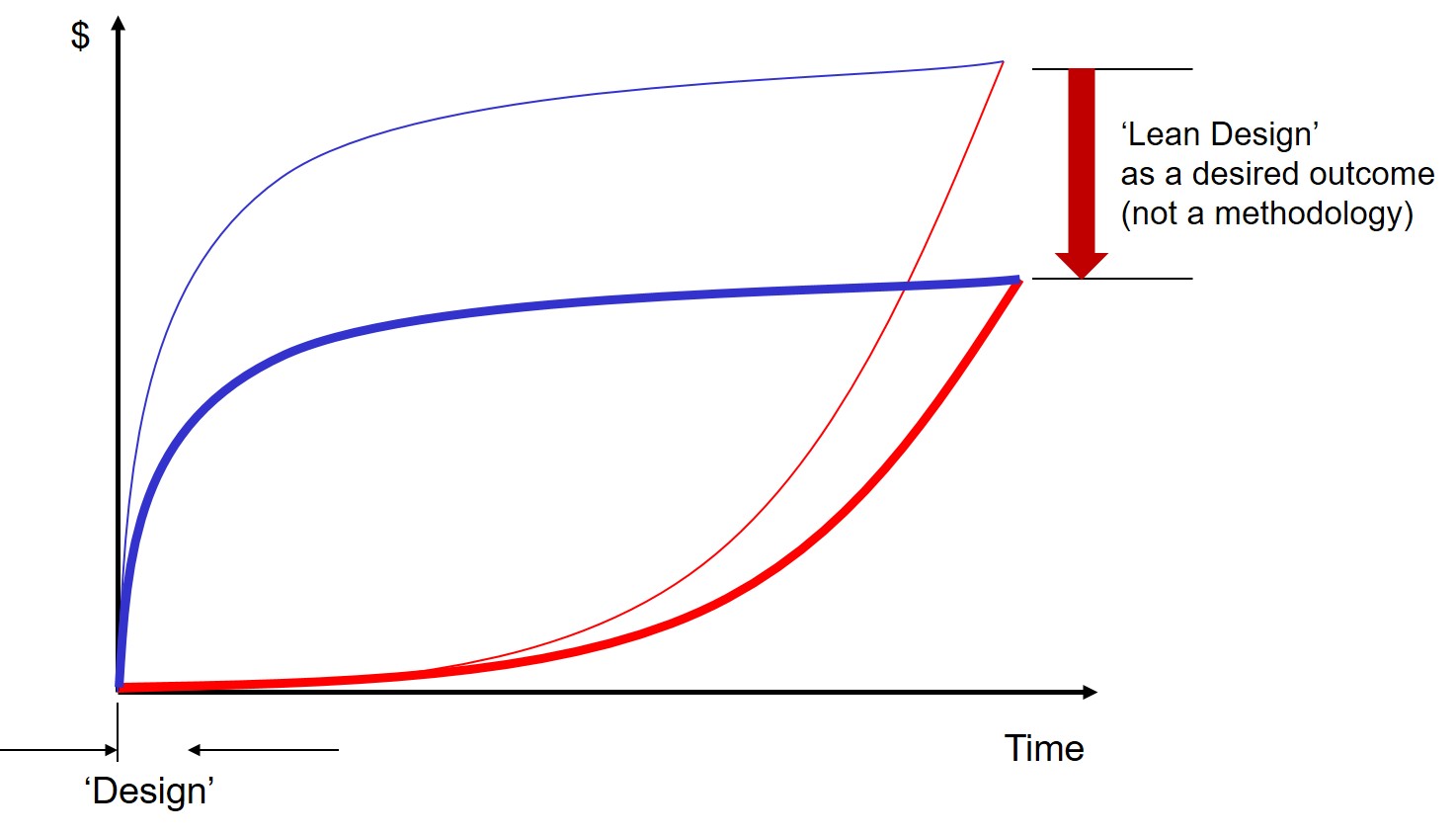

The only thing that ‘Lean Design’ contributes to this story is that it recognises the desirability of reducing the overall cost of projects…

…beyond that, rather like Axiomatic Design, it has nothing useful to contribute to the story of how to actually achieve the stated goal. The tools are wrong, the methods are wrong, and the overarching thinking is 180degrees wrong. If a ‘Lean Design’ consultant approaches you with a promise they can reduce your project ‘waste’ your best bet is to laugh at them.

If you’re feeling mischievous, you could ask them what they know about complex adaptive systems. Or contradictions. Or intangibles. Then notice the look of confusion and horror on their faces. And then laugh at them. With a following wind, like Professor Suh, garden slugs and Dengue-fever they should be gone within a couple of years. In the meantime, try and keep smiling.