Every complex problem has a million simple wrong answers. If you’re lucky – if you can get to the core principles of the system – you might just find a simple right answer. Most people don’t get lucky because they don’t know how to get to the core principles. Most people don’t get lucky because they listen to supposedly smart people who also don’t know how to get to the core principles.

Take Frederick F. Reichheld, the man that wrote, ‘One Number You Need To Grow’ in 2003. What manager wouldn’t want to know what that ‘one number’ was? It was a sure-fire Harvard Business Review hit, and it spawned the monster we now know as Net Promoter Score.

The one number starts from one question. Even simpler. “On a scale of 0-10, how likely is it that you would recommend our company/product/service to a friend or colleague?”

It’s a simplicity that turns out to be flawed on so many levels it’s stops being funny after about five minutes. The laughter turns to tears when Frederick F Reichheld spotted that a good Net Promoter score was correlated to company share price.

Despite the fact that Reichheld himself eventually worked out that he’d fallen into the correlation-isn’t-causation bearpit, it was too late. Every Fortune500 company in every Fortune500 listing had taken for the bait, and so a whole industry of NPS surveyors found themselves riding a gravy train that still feels like one of the greatest gravy trains in the history of gravy trains.

The rules of the Hype Cycle – fortunately – tell us no ride goes on forever. Some will die outright. Those that have some underlying merit will prevail, once everyone works out what the underlying merit is. And, more important, how to meaningfully get to it.

Given the choice of knowing or not knowing whether I’m making our customers happy or not, the responsible side of me thinks I’d rather know. That’s the ‘underlying merit’ of NPS: knowing whether my customers are actually happy. Whether or not I can meaningfully know that my customers are happy or not, and – more importantly – knowing what actions I should take to make sure everything is moving in the right direction, becomes the critical question.

Answering it requires at least three things:

1) I need to know that my customers are telling me the truth

2) I need to know the local context within which they gave me their answer

3) I’d like a measure of a customer’s ‘threshold for action’

Current NPS assessment methods fail on all three counts.

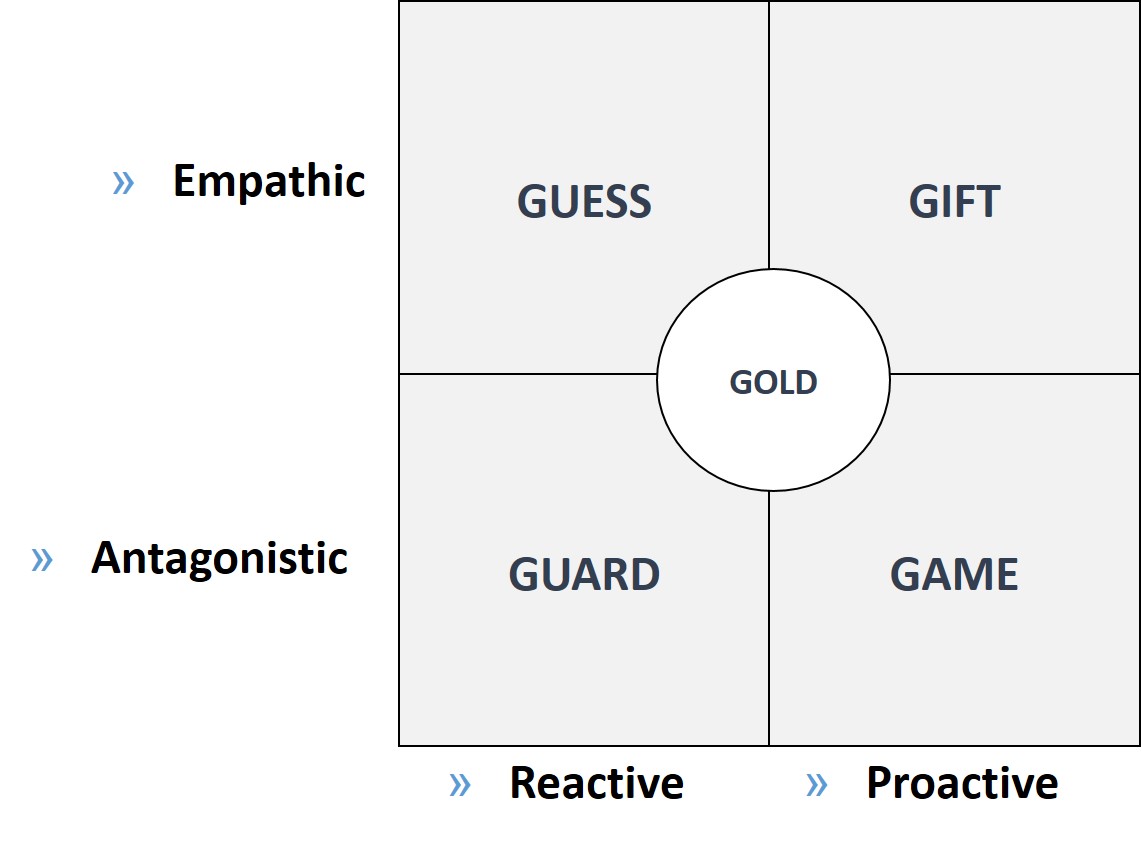

The first of the three is probably the easiest one to put right. Or, it is if you are using PanSensic and are able to map where a customer’s responses are on the 5Gs model:

Where you are on the map depends on a whole bunch of (measurable) things. One of them is your level of (over-)familiarity with NPS questions. Picture, if you can, the very first time you read that ‘how likely are you to recommend…’ question. You were probably in a restaurant. And it was probably part of a chain. Your surprise and lack of familiarity with the question probably meant you were intrigued. And very probably intrigued enough to do some actual, proper thinking about your answer. You were likely somewhere in the Golden middle of the 5G graph. Which was good for the restaurant. Now, bring yourself back to the present day, where it’s quite likely you’ve been asked ‘the question’ a couple of times during the last week. Not just in restaurants now, but on trains, at the airport, in the supermarket, at the mall, in the hospital. I even got asked it at a football game last month. Now you don’t think about your response any more. You probably have no inclination to respond at all. If you do feel inclined, it’s most likely because something extreme happened. Something extremely above-and-beyond-the-call-of-duty, or something horrendously bad. In neither case, though, are we going to answer the question objectively. That’s because the NPS question has progressively numbed our senses to the point where it has become meaningless the moment we see or hear it.

Local context is more difficult to capture, but still within the realm of possibility given the current range of different PanSensic lenses. Context, in terms of my likelihood or otherwise to recommend your products or services to my friends, has everything to do with the difference between correlation and causation. When I was asked whether I would recommend my friends to come and attend a game at the football club that asked me the question last month, the most sensible answer I could’ve given is ‘I’m an away supporter, I only came because my team is playing here.’ My actual likelihood of attending that club again – the causal link – is solely about whether they are in the same Division as my crappy team next season. I’m slightly ashamed to say that my actual answer to the questioner was, ‘yes, I am very likely to recommend your football club to my friends’. I watched as the questioner ticked the relevant box on her nifty Likert Scale. We were both happy. She was happy because she had something to correlate. The main reason I was happy, however, was because my crappy team had just beaten their even crappier team. If I’d been pushed any further, I’d very likely have made the request – as many of my fellow travelling fans chanted during the game – ‘can we play you every week?’ My reason for giving the answer I did, in other words, had precisely nothing to do with the way my answer was going to be interpreted.

So much for the situational aspect of ‘local context’. If you’re analysing the narrative around the answer rather than the score on the 0-10 scale it’s relatively easy to pick up this sort of situational effect. Ditto regarding whether someone is qualified to answer the question in terms of domain knowledge. I’ve been down this rant path before. Usually with things like Trip Advisor where the ‘reviews’ I read are usually written by people who stay in a hotel once in a blue moon and consequently have no way of saying this particular hotel is any better or worse than any other one on the planet. Their ‘review’ is usually – for the sorts of hotel I tend to stay at – based on a comparison between their experience and an advert they saw on TV for a seven star hotel in Dubai. i.e. fiction piled on fiction. “The taps weren’t even gold, two stars.”

The third aspect of ‘local context’ is the context of the person I might consider recommending your products and services to. I like music. I own a building full of records, tapes and CDs that aren’t going to be digitised and disposed of any time soon. When visitors see my music collection, they usually ask me to recommend something to them. A question that I can only usefully answer provided I know something about the sort of music they currently like. And how far in or out of their comfort zone they might want to go. And how much I want them to come back and ask for more recommendations in the future. It’s rarely as straightforward as saying, ‘Blue Nile, Hats’, although, I know that particular recommendation will work more often than it won’t, and if it doesn’t work, the visitor won’t be invited back very often in the future anyway.

Last up is ‘threshold for action’. This is the most difficult of the meaningful-NPS desire foundations. To an extent we know it boils down to the strength of the adjectives that people use to describe their experiences. Or rather the relative strengths.

Back to my football match. At half-time I – unusually – decided to go and get a cup of tea. There was a queue. I was stood behind a father and son duo. The son looked like he was about eight, and sounded like he hadn’t been to an away game before. Everything, therefore, was ‘awesome’. The journey to the ground had been awesome. The sandwiches were awesome. The floodlights were awesome. The two goals we’d scored were awesome. The late-night return home was also going to be awesome.

He was basically me forty-five years ago. Now I know that most things aren’t awesome. Our second goal, as it happens, was pretty awesome, but the first one was an umissable tap-in following a bad mis-kick by one of their defenders. It was never going to win any goal-of-the-season competition any time soon. Likewise, my cup of tea, when I eventually reached the front of the queue, tasted like it had been brewed a fortnight earlier, and had long past its moment of awesomeness. It doesn’t take much for an eight-year old to see that everything is awesome. For a cynical old man, awesome doesn’t happen very often any more. When it does happen, though, it probably means more in terms of useful feedback to a company than when they hear the same adjective come out of the mouth of the eight-year-old.

You need a lot of an individual’s narrative in order to calibrate their adjective use in order to work out where they need to be on an adjective-strength spectrum before they will act – i.e. recommend to their friends or family. Getting access to sufficient of this narrative is ‘possible’ if you have access to, say, the Facebook narrative of a smiley Millennial, but very often the people that talk the most are the ones with the least to say. In which case, the current ‘best’ way to calibrate the how well a customer thinks about you is to calibrate across many customers. Even better, thinking about the PanSensic ‘Mental Gear’ lens, is to calibrate across Blue, Orange, Green and (especially) Yellow customers, and then – most crucially of all – close the loop by finding some actual customers that actually did recommend you to their friends and family and examining their actual collective PanSensic profiles.

NPS is not as far along the maturity scale as other Weapons of Mass Distraction (Balanced Scorecard, SixSigma, QFD, PRINCE2, Scrum, Agile, etc). Unlike most of them, it at least has a valid start-point in that measuring customer emotions is a fundamentally good thing to do. Whether it gets to survive in the long term is largely dependent on how quickly it can evolve to a point where the measurements it’s is used to make are meaningful – as in truthful, context-relevant and actionable. Which is hopefully where PanSensic comes in to play.