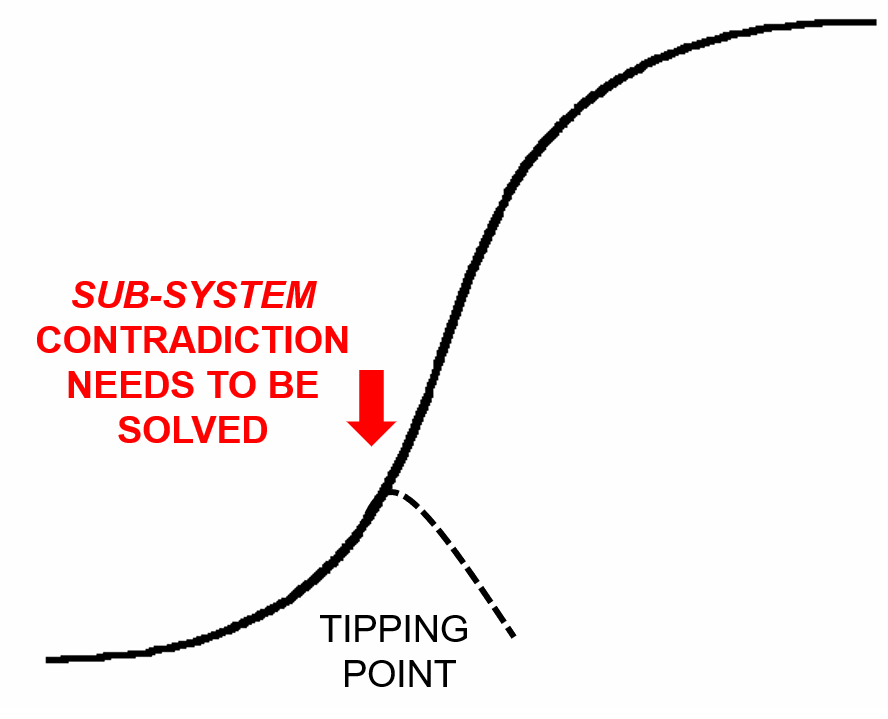

When we’re trying to reduce the world and how it works down to first principles, there aren’t that many universals. One of the clearest – if you know what you’re looking for – is the S-Curve. S-Curves are literally everywhere. Because they describe the fundamental behaviour of systems, and systems are everywhere. When a system experiences a (positive feedback) virtuous cycle, we get the first, rising, half of the curve, then, eventually the system will experience a (negative feedback) vicious cycle which will cause the second – diminishing returns – part of the curve.

Most ‘systems’ aren’t planned, but emerge naturally. A murmuration of starlings being a good example. Our planet, to take a rather bigger example, is another emergent system. That’s what James Lovelock’s ‘Gaia’ idea is all about (despite the fact that the woo-woo, Pagan-gods-and-incense, New Age brigade would like to thing otherwise).

Any system that humans intentionally create is subject to the laws of the S-Curve, but because we’re deliberately trying to design a successful new product, or encourage customers to subscribe to a new service, if we want to achieve a successful climb up the curve, we need to understand what we need to do (and not do) at each critical stage. How to create a virtuous cycle? How to delay the arrival of vicious cycles? Or, better yet, how to overcome the vicious cycles and enable a discontinuous shift to a new curve?

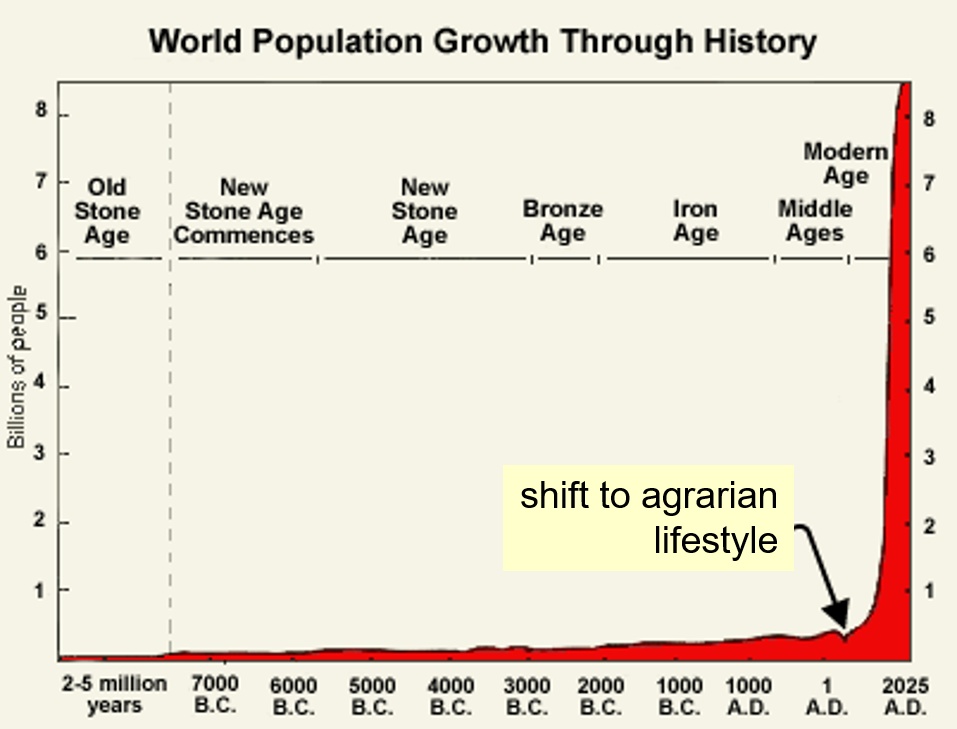

One of the more subtle, but nevertheless fundamentally-present and critical points on the curve is what we currently know as the ‘tipping point’. This is the point when a system successfully transitions from the early struggle and on to the steeply rising part of the curve. This Tipping Point is usually very subtle in nature since natural systems often emerge over quite long periods of evolutionary time. The easiest way to see them therefore involves zooming-out and looking at things over long periods of time. If we zoom out far enough, the human Tipping Point begins to look very obvious:

One could say that for most of our evolutionary history, humans played a tiny role in the ecology of the planet. Humans were a niche and the S-Curve of human population shows near stagnation. We only hit our Tipping Point after our long-ago ancestors invented farming. Once we stopped having to be nomadic and started building stable settlements that we started to achieve the economies of scale that meant new born infants were more and more likely to survive, and then, post Tipping Point, began the steep rise to levels that appear today – somewhere near the top of the curve – to no longer be sustainable.

A bit like the way biologists do a lot of their experiments with fruit-flies because the breeding time is so rapid, one of the best places to see a more detailed picture of the dynamics of the Tipping Point is to look at popular music. An industry where we get to see many thousands of attempts to create ‘hit’ artists every year. Almost every musician strives to be popular (if only to pay the bills), but the vast majority find themselves unable to get past a Tipping Point of popularity that allows them to sustain a long term career. Better yet from a study perspective, every artist is expected to create new music on a regular basis. Musicians are in many ways the fruit-flies of the S-curve world.

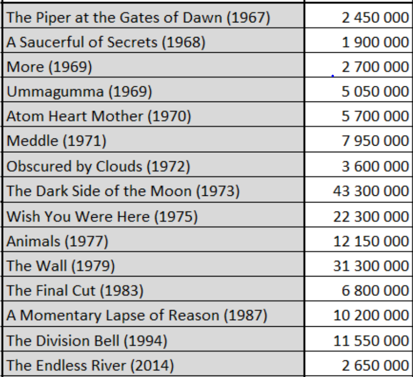

Take one of the best selling artists of all time, the band Pink Floyd. Here’s a chronologically ordered list of the sales of their albums:

The band hit the world in the late 60s and made an immediate impression on the record-buying public. They sold enough of their debut album to be afforded the opportunity to record a second. The second one, by all accounts, wasn’t as good, but it still sold enough copies that the record company sanctioned a third. This did a bit better. The fourth did better again. And so did the 5th. But it was only when 8th album, Dark Side of the Moon hit the shops in 1973 that the band found their Tipping Point. 5 million sales per album now jumped to 43 million. The band was, quite literally, set for life.

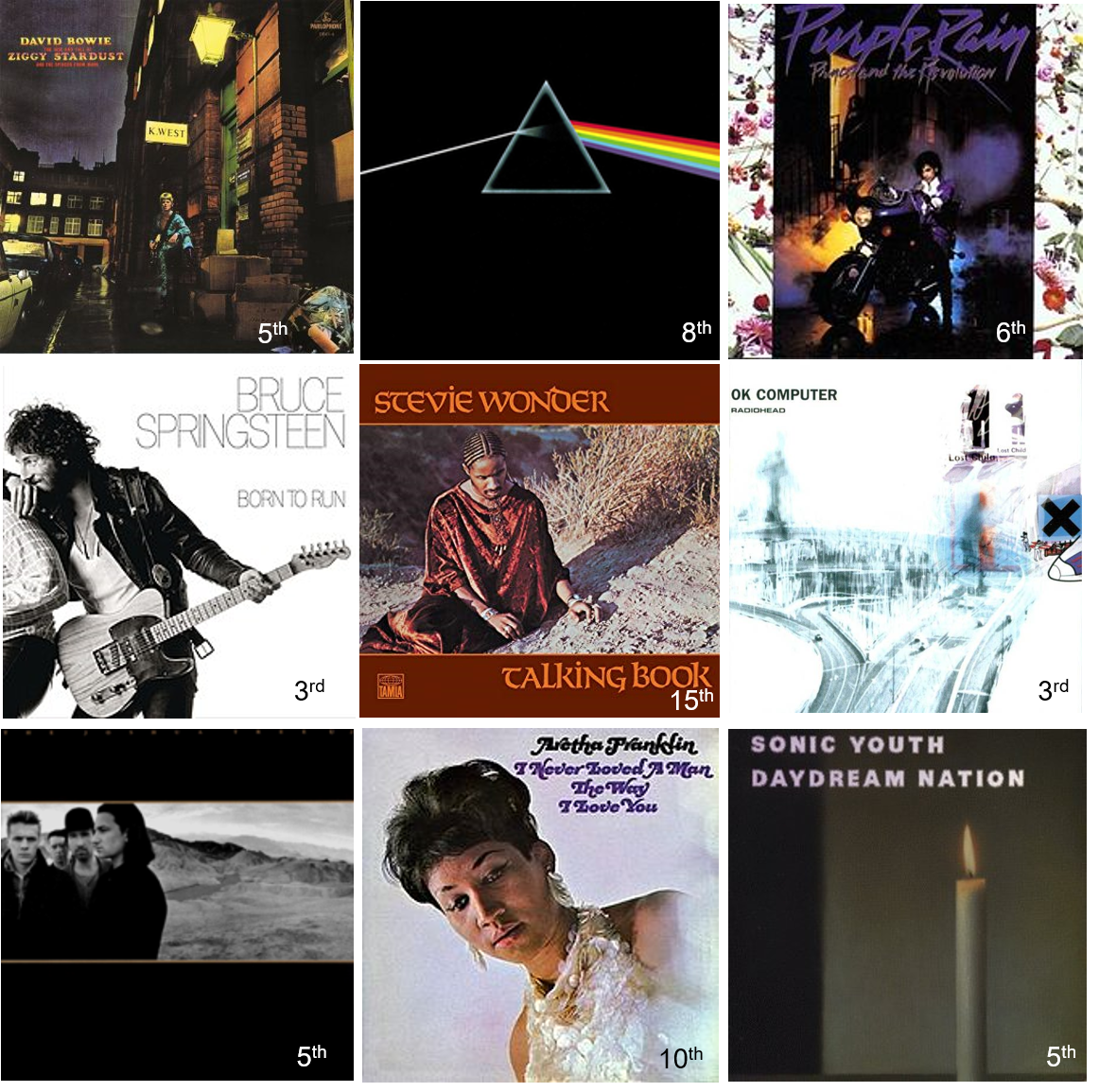

We can plot similar trajectories for other artists that successfully crossed this ‘set for life’ Tipping Point. Here are a few you, depending on your age, probably know:

The main thing to note with all of them, I think, is that Tipping Points don’t happen right away. Radiohead managed to go stratospheric after only their 3rd album, but it took Stevie Wonder 15 attempts before he properly climbed his popularity S-Curve and became a global superstar. On average, artists seem to need somewhere between five and six attempts.

So, one characteristic of the journey to Tipping Point seems to be trying different things. The other, more subtle one is that in each case some kind of internal (i.e. directly related to the artist rather than their audience) contradiction was solved. With Dark Side Of The Moon, the band finally worked out how to write songs, and, crucially, Roger Waters had the good sense to connect them all to an over-arching theme that would resonate with large swathes of music fan. With Stevie Wonder it was successfully fighting against his record company that he was a serious album artist and not just about pop singles. With Radiohead it was being allowed to produce the album themselves and not be bound by a similar record company pressure for singles. Aretha signed with Atlantic and went to Muscle Shoals. Springsteen stopped trying to be Van Morrison, dumbed-down the words, turned up Clarence’s saxophone and started listening to music journalist come-strategist, Jon Landau. And so on. The basic – universal, first principles – message being, if you want your system to get successfully beyond its Tipping Point, you need to find the internal, sub-system, contradiction(s) and solve them.