Many of us inadvertently shoot ourselves in the foot once in a while. Occasionally – and usually rather more spectacularly – we get to observe large groups of people embarking on a collective foot-shooting extravaganza. The expenses scandal by British politicians a few years ago was one of the most visible examples of such synchronized stupidity.

Not surprisingly, the aftermath of that scandal saw the introduction of a more rigorous set of expense-claiming guidelines. And thus the pendulum swings from ‘it’s okay to clean your moat on expenses’ to ‘itemise everything down to the last penny’. An outsider might nod at this point and say, fair enough, they’re public servants and they need to be punished for their excesses. What better way than forcing every politician to cram their pockets with receipts? Especially if we then make all of their transactions available for public scrutiny.

And so now, as a population, we’re able to sleep at night safe in the knowledge that David Cameron’s recent claim for the cost of a £4.68 glue stick and 8p for a box of clips has been duly claimed and paid. Or that Vince Cable legitimately spent 43p on scissors (which Poundsaver did he got to for them??), or that Kenneth Clarke charged the taxpayer 11p for a new ruler.

I don’t know about you but this is the sort of thing that tends to make me think the UK government accounting system is dysfunctional. Not because of the perception I have that the cost of processing the claim is likely to be much more than the claim itself, but rather because it demonstrates such a fundamental lack of understanding of human psychology.

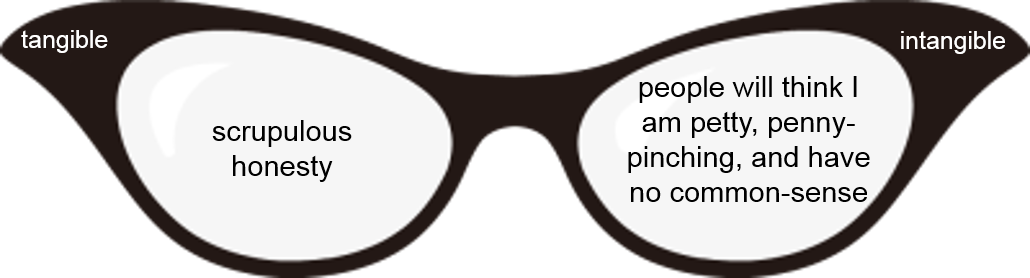

People do things for good reasons and real reasons. We all look at the world through tangible and intangible lenses. The tangible lens is the rationalizing lens, in this case, of the accountant. In the accountant’s eyes, accounting everything down to the last penny is the absolute right thing to do in order to demonstrate scrupulous honesty. The intangible lens, on the other hand, is the lens of emotions and difficult to quantify things like common-sense and gut-feel.

Looked at through this lens an expenses claim for 8p begins to look quite different:

- How petty-minded does a person need to be that they even contemplated making a claim?

- Did this person have so little common-sense perspective on the bigger picture costs of processing a claim?

- And if so, and I extrapolate to everything else, what damage must they be causing to the country?

- And, anyway, how incompetent must the Downing Street office staff be to have a stationery cupboard so poorly stocked that there was a need to pop-out to Staples to go buy a box of clips?

- Bearing in mind his £142,500 salary, what possible difference could 8p have made to David Cameron?

All in all, what this tangible scrupulous honesty plus intangibles-blindness combination does is creates a perception that claiming for an 8p box of clips might be a far worse crime than the multi-thousand pound moat-cleaning claim. Looked at through the intangible lens, an 8p expense claim is likely to make people trust politicians less rather than more.

Any normal person would, I think, have been too embarrassed to enter such trivia on an expenses claim form. A normal person sees the world through both tangible and intangible lenses.

Not only that, all the research also tells us that we see things through the intangible lens before the tangible one. It’s our inbuilt instinct. Looking through this lens first is a really good way of avoiding shooting yourself in the foot. For some difficult to fathom reason, people in public life – or the pencil-licking, more-than-my-jobs-worth bureaucrats they recruit to look after them – seem to re-train their instincts to ignore the intangibles. On one hand, overriding ones natural instincts is quite a feat. On the other, the day you start believing that your rightful claim to that 8p is more important than the possibility that everyone around you might think you are a petty, no-common-sense dick is probably the day you should contemplate withdrawing to a quiet life of pottering in the shed at the end of the garden.