The previous Facebook Mission Statement, “Making the world more open and connected” had one fundamental flaw: it didn’t push for any specific positive outcome from more connection. Technically, it could encompass digital voyeurism via the News Feed, trading in-person friendship for online acquaintanceship or the filter bubbles and echospheres that have further polarized the United States.

So last year, as Facebook approached 2 billion monthly users, its CEO Mark Zuckerberg revealed a new mission statement, to “Give people the power to build community and bring the world closer together.”

Zuckerberg announced the change at the Facebook Communities Summit for top Group Admins where it announced new Group management tools. “For the last decade or so we’ve been focusing on making the world more open and connected. But I used to think that if we just give people a voice and help some people connect that that would make the world a whole lot better by itself,” Zuckerberg admits. “Look around and our society is still so divided. We have a responsibility to do more, not just to connect the world but to bring the world closer together.”

Rather than have the new mission be just a philosophy, Zuckerberg says Facebook is turning it into a goal. “We want to help 1 billion people join meaningful communities. If we can do this it will not only reverse the whole decline in community membership we’ve seen around the world… but it will also strengthen our social fabric and bring the world closer together.”

It all sounds so great. Until you actually think about it. Until you bring some actual knowledge to bear. But then, isn’t that the problem of so much of the Silicon Valley story these days. A fatal Ignorance-Arrogance delusion. Naïve good intentions ending up in horrendously harmful and damaging consequences for everyone else. (Although not necessarily for the Facebook share price. Hmm.)

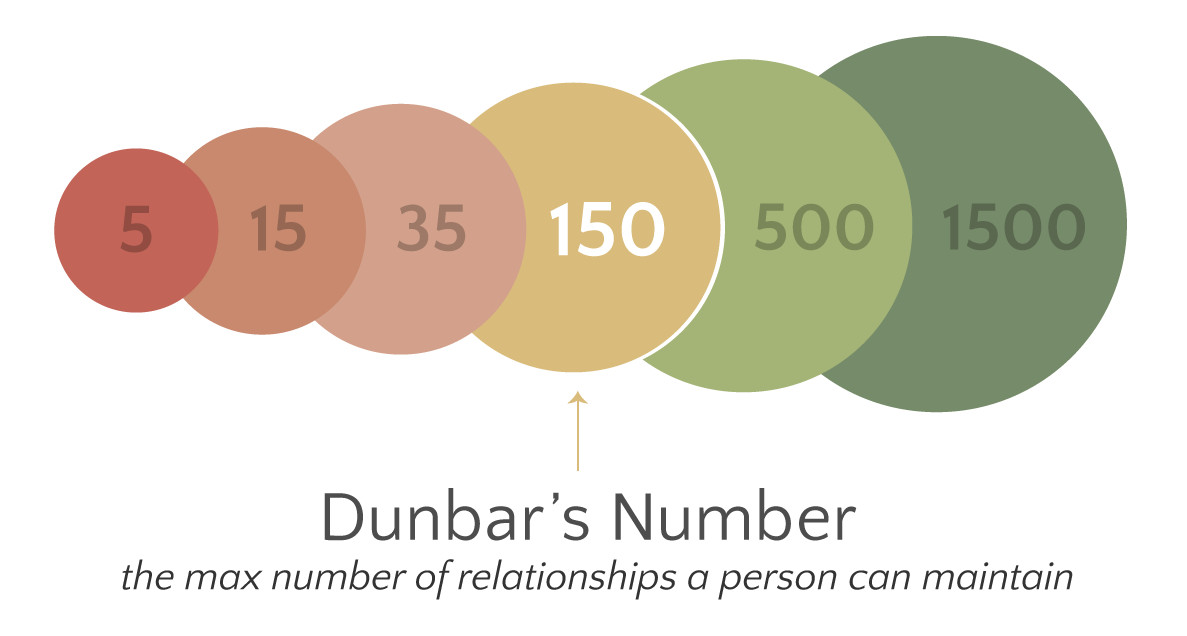

Let’s look at a quick example. I happen to be a fan of anthropologist, Robin Dunbar, most famous these days for the Dunbar Number: the maximum number of people we are able to maintain relationships with. Which turns out to be around 150. Plus or minus, depending on the way your brain works.

Now, for me, if Dunbar is anything close to right, the Dunbar Number alone tells us there is no such thing as a world-size community (see also my blog, ‘The Plural Of Community?’). And that as soon as we create a 150-strong community of ‘us’, we, by definition, create another much bigger community of ‘thems’.

As if to prove my point, I knew I wouldn’t have to look very hard in order to find a community of people who didn’t believe in the Dunbar Number. ‘The Fallacy Of Dunbar’s Number’ popped up at the top of my search (https://www.fullcontact.com/blog/maintaining-relationships/). A better example of exception-proving-the-rule I’d be hard pushed to find. Brad McCarty is the author of that blog. He has a ‘solution’ to the Dunbar number that involves building a personal taxonomy of contacts for all the different topics he’s interested in. Funnily enough, each of these topic-communities seems to end up containing around 150 contacts, but hey, once some people have made their mind up that something is wrong, they’re not going to change no matter how much evidence they’re given. Now, if I imagine that every person on the planet follows Mr McCarty’s advice, and, let’s say each of us is capable of juggling a dozen or so of these topic communities in our fragile, overloaded little heads, then what we’ve also contributed to are a dozen topic communities with the opposite view to our own.

If we reduce everything down to first principles, the human brain has thus far evolved to categorise three types of people: me, us and them. For every ‘us’ we create or participate in, one of the things that unites ‘us’ is our rejection of the nearest ‘them’. Zuckerberg’s naïve desire to create ‘meaningful communities’, laudible as it might be, is utterly – utterly – inconsistent with ‘bringing the world closer together’. Point one, there is no plural of community. Point two, every meaningful community that gets built sparks the creation of its opposite. It’s very possible to create ‘communities’, but when you do that, you don’t bring the world together, you create lots and lots of polarised views that make it progressively less likely that people are able to talk to each other any more.

Unless you know how to recognise and solve the contradictions you’re creating. Which delusional, ivory-tower-based social media oligarchs like Mark Zuckerberg, sadly, appears to be heading further and further away from. Good intentions often create terrible outcomes. Good intentions that fail to understand the first principles of human behaviour, simply create terrible outcomes faster.