If I believe in the Lindy Effect, the most antifragile industry ought to be the oldest industry. There’s probably a lot of truth in that idea. Except there’s a problem: the oldest industry, as far as I can tell, is an industry that still consists for the most part as large numbers of individual, ahem, ‘artisans’.

Artisans are one of the few instances of life’s skin-in-the-game heroes if I read Nassim Taleb’s work correctly. The other heroes are entrepreneurs.

There’s a problem here, I think. For society to function, there are things that need to be done that go quite some distance beyond the capability of individual artisans and entrepreneurs. For the thirty-plus people attending the AntiFragile get-together in London on Tuesday, for example, their timely arrival was only made possible thanks to the coordination of several thousand employees of Transport For London.

Looked at in that sense, I think there’s a need to re-calibrate the ‘antifragile industry’ question. To some extent, TFL – and other large enterprises – do what they do with thousands of employees who have little skin-in-the-game above and beyond the possibility they might lose their employment if they don’t do the work that’s asked of them. But then, to quote W. Edwards Deming, ‘no-one comes to work to deliberately do a bad job’. Despite the dumb things I sometimes see bosses asking them to do. Maybe a half-decent salary and a desire to serve the customer, when scaled up to include each individual in the organisation is sufficient to deliver requisite collective skin-in-the-game at the enterprise level? Maybe the individuals that put up with the crap dished down to them from above and still do a great job for their customers are the real heroes in life? Maybe it is this sense of collective responsibility to do the right thing that keeps society on an even keel?

Either way, I think there’s something significant missing from Taleb’s perspective on the heroes and villains of modern life. To divide the world into individual skin-in-the-game heroes and the villainous rest represents a failure to accept the possibility that we don’t live in an either/or world. It is possible – as nearly every large enterprise on the planet demonstrates – to have the best of both worlds. Not every organisation, of course. I completely agree with Taleb’s perspectives on organisations like Monsanto or, my own ‘favourite’, SAP, in both cases collectives of individuals – none of whom come to work to do a bad job – that can very easily be seen to deliver considerable collective harm.

One hopes that organisations like this will prove to be very fragile. 90% of the enterprises on the original Fortune 500 list no longer exist. They turned out to be very fragile indeed.

So what about the large enterprises that do prevail in the long term? Which of them is the most antifragile?

In my opinion, the answer to this question is the aerospace industry. Even though it has only existed for the last hundred years. By definition, everything that happened after the Wright Brothers flew at Kitty Hawk in 1903, getting people into the air safely has demanded large numbers of people working together. And because the industry very quickly learned that when people die in aeroplane crashes that is very bad news, ‘safety’ became the absolute. It therefore embarked on a very rigorous journey of building better and better safety protocols. At the same time, I might add, as also constantly innovating. The 100 year jump from the Wright Brother’s efforts and an Airbus A380 is quite mind-blowing if you think about it.

The aerospace industry is the most antifragile because it has to solve the safety AND innovation contradictions every day of its existence. And that is only achieved by making sure everyone in the industry learns from anything and everything that ever goes wrong. Every incident is investigated and the findings are shared across the industry to make sure the incident has as little chance of being repeated as possible.

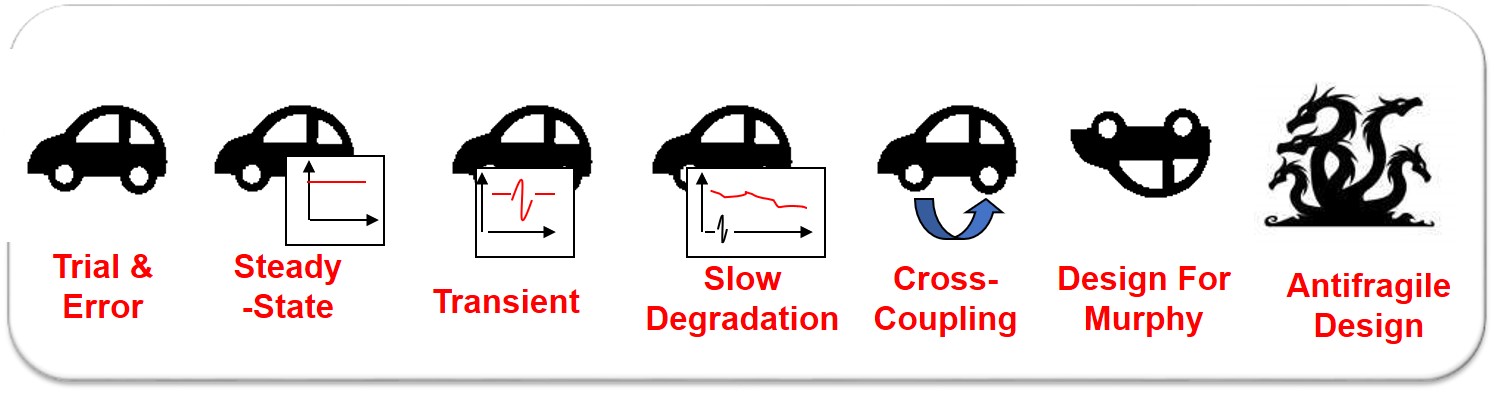

As it happens, I started my career in the aerospace industry. I worked there for fifteen years. When I left to begin working in other domains, it took me a while to realise that not everyone saw the world in the way that had become the norm in aerospace. The cognitive dissonance was one of the things that prompted us to reverse engineer the evolution journey of the industry and to formulate the ‘Resilient Design’ evolution trend pattern:

Tracing back through the evolution of the design methods deployed in the industry, it was possible to identify a number of step-changes in capability. Design method s-curves if you like. That’s what each stage on the trend picture is intended to represent.

The latest stage on the trend – ‘antifragile design’ – is where I think the industry is pretty much at these days. In the 1990s we used to talk a lot about – and design for – ‘Murphy’. In a Design-for-Murphy world you’re forced to accept that customers will occasionally do stupid things, but that when they do such things, the aircraft should still be resilient enough to make sure that everyone gets down onto the ground again in one piece. Nowadays, thanks to scenarios like GermanWings Flight 9525, when a co-pilot decided to commit suicide with 144 passengers and five other crew members on board, the industry has evolved capabilities to ensure it’s a one-off. The outcome for the 150 unfortunate souls on Flight 9525 wasn’t good, but for the rest of us, their story means we can take to the skies safe in the knowledge that the aerospace industry was made stronger as a result.

When I look at – and work with – other industries, one of the first things I look to calibrate myself on is how far along the Resilient Design trend pattern are they – actually, we should be looking to rename the trend ‘AntiFragile Design’ – in order to better understand how we set about innovating with them.

Transport For London, much as they succeed in getting millions of commuters to their destination kind of on time most days of the year, is still essentially at the second stage of the trend. As anyone who’s ever tried to get across London following the (transient) arrival of half an inch of snow will attest, there are days when the system is very fragile indeed.

Someone at the AntFragile meeting earlier this week asked me whether it was possible to use this trend-pattern way of thinking to decide where to invest money. I’ve forgotten the answer I gave at the time, other than remembering it was horribly glib. If I could turn back to the moment of the question again, I think I’d probably answer that I don’t invest in any kinds of stocks or shares because I can’t think of any bank or broker that’s ever reached the third stage of the Resilient Design trend. Also, I don’t know whether its possible to invest in an ‘industry’… i.e. I’d quite happily invest in the antifragile aerospace industry, but am somewhat less clear about investing in any individual aerospace company, given the potential possibility that at any given moment they might have a very fragile management team in charge. I think, if I could ever motivate myself to spend time thinking about stocks and shares, I would very definitely do it by looking at the Resilient Design (AntiFragile Design) level of the enterprises I’m thinking of investing in. Which, thinking about it, is the reason why I don’t invest in anything other than our own business. And the things we occasionally spin-out. We know the trend pattern, but we’re still very much in the minority. The vast majority of enterprises on the planet don’t know the pattern and therefore, in my eyes are all very fragile. Even if they might happen to have a lot of money stashed away in the bank at the moment.