“You think intelligence and grit can succeed by themselves, but I’m telling you that’s a pretty illusion.” Nancy Kress, Steal Across the Sky

“Anyone can be tough for a season. It takes a special kind of human to rise to life’s challenges for a lifetime.” Chris Matakas, The Tao of Jiu Jitsu

We’ve been doing a lot of psychometric analyses of innovators in the past few months. Trying to establish whether there is some kind of universal ‘DNA’ of the successful. Turns out there is. At least on one or two dimensions. Talent is one. Having talent helps. But grit, it seems, helps more. Having both is better still.

And that’s where things seem to go astray. For the most part, it seems talent and grit form a relationship that is strongly either/or. People with natural talent tend to assume that it alone will help them to get on in life, and so they tend not to score highly on tenacity, persistence and all those other human attributes we integrate together to define ‘grit’. People with less natural talent, on the other hand, if they want to get on in life, usually do so by compensating for that lack of talent through large amounts of grit.

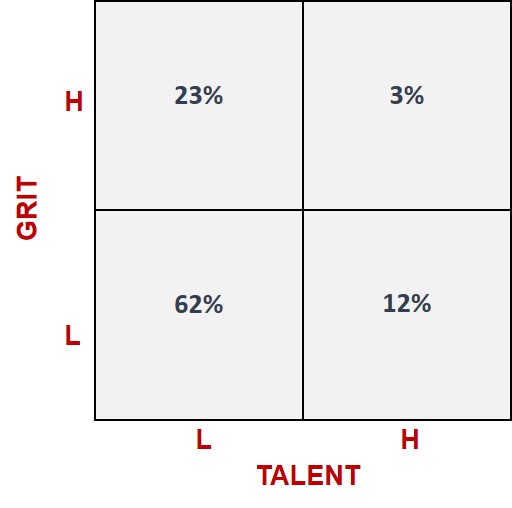

According to our measurements in and around the shady world of innovation professionals, we estimate the following split between the four different combinations of high or low talent or grit:

Although we can’t definitively make a causal link between innovation success and where people sit within this 2×2 matrix, the evidence makes it pretty clear that the small proportion of contradiction-solving people in the high-grit-high-talent quadrant are the ones that generate the highest level of success.

Instinctively, I doubt whether many people would argue with the basic idea. That’s what ‘solving’ contradictions is all about: if we achieve the best of both conflicting attributes, good stuff happens.

The surprising part is perhaps why so few people end up in the quadrant. 3%? How could that be?

Maybe it’s a case of emergent behaviour? The world gets precisely the right amount of innovation because it has exactly the right number of high-talent-high-grit individuals? But then again, with 98% of innovation attempts ending in failure, maybe if organisations need to do better, they need to encourage a higher proportion of their people to get into the top right quadrant?

If that’s the case, what are the problems that needs to be solved?

As is often the case in these kinds of situation, it is instructive to look at extreme cases in order to really get to the heart of the problem. In this case, I think a really good extreme involves the music industry and famous musicians. Particularly solo artists.

Example one, Van Morrison. I love Van Morrison’s music. Or at least I love what he released before 1991. And, if I’m really being honest and look at the stuff I repeatedly listen to, before 1982. He’s a man with an enormous amount of talent, but it was only when he combined it with grit that he produced what – I think – is truly great music. During the 1970s he was, and no doubt, f you read interviews, felt massively mis-served by the music industry. He was the archetypal ‘musician’s musician’ gaining lots of critical plaudits, but very little apparent reward. He was angry at the world and he managed to direct the anger productively into the music. Then he got successful. The plaudits grew. He took his foot off the accelerator. Still the plaudits kept coming. He could virtually do no wrong in the critics’ eyes. The more half-hearted the music, the better they seemed to like it. So why try? The grit disappeared.

I’ve seen him five times in concert. Two times he was absolutely spell-binding. Three times he gave the distinct impression he wasn’t interested. Contractual obligation was the only thing keeping him on the stage. Needless to say the two times I stayed to the end were in the grit-and-talent years.

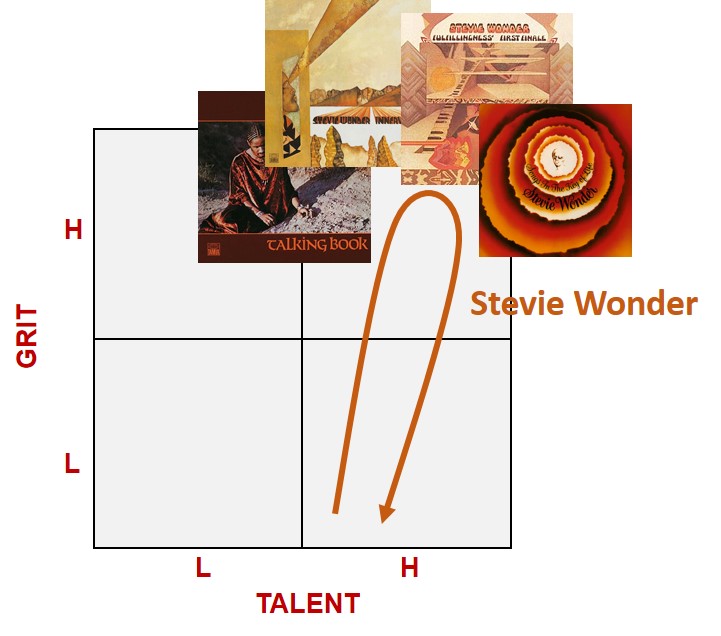

Example two, Stevie Wonder. Again massively talented. But only during the period 1972 to 1976 do I feel like he was really trying. Those were the grit years. Grit for a slightly different reason than Van Morrison. Wonder, from the age of 12, had always been a commercial success. His problem was that he wanted to travel his own path, not the one his record label wanted. He could’ve towed the line, but he had a bigger vision, and, after his 21st birthday, he put his foot down. Enter the grit. And a run of four consecutive classic albums.

Check out http://www.i-sim.org/icsi2017/Keynotes&Tutorials.html a global compilation of every recording artist’s reviews ever, and notice just how far ahead of his other albums they are. After he’s proved is point, he again appears to take his foot off the pedal. Life gets easy and there’s nothing to fight against anymore.

It’s possible to do just about the same search for every other major artists. Check out their ‘best’ albums and they’re always from a ‘grit’ period. Rolling Stones? Threw away the grit after 1978. The Who? The grit disappeared in 1978. Eagles? 1976. The Beatles? 1970.

Actually, the Beatles appear to offer up an interesting new angle on the talent-and-grit story. The grit part stemmed first and foremost from the competition between Lennon and McCartney: if Lennon wrote something good, McCartney felt compelled to better it. And vice-versa. After they were unable to be in the same band together, neither of them produced anything truly great ever again. There’s a case to be made, too, I think, that McCartney was the talent and Lennon was the grit. Either way, the Beatles offer up the thought that talent-and-grit can be a collective affair. A lot of great songwriter pairings – Morrissey/Marr, Page/Plant, Goffin/King Strummer/Jones – seem to prove the point. Two points: two or more different individuals can serve up a talent-and-grit whirlwind if the conditions are right, and secondly, they tend not to be able to sustain it for very long. Fighting the talent-and-grit contradiction requires hard work.

Very few individuals manage the sustainability feat either if the music industry serves as any kind of model for the world. Prince, maybe? Miles Davis? Keith Jarrett? Maybe they’re the people we need to go study more deeply if we really want to solve the contradiction.