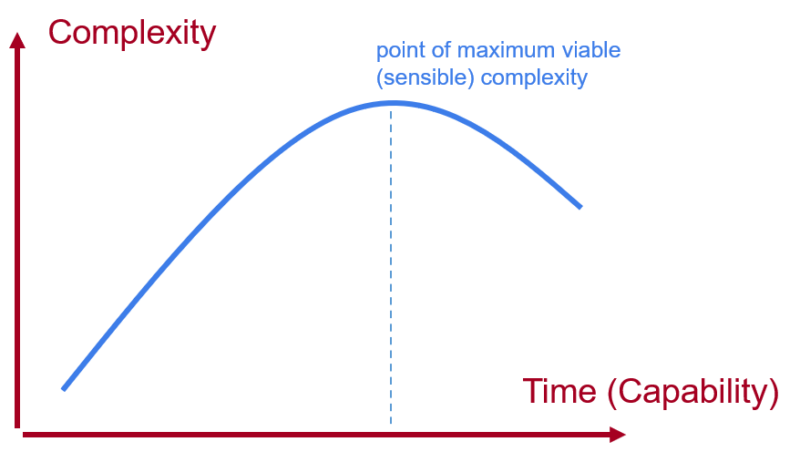

One of the main TRIZ Trends of Evolution, ‘Mono-Bi-Poly’, describes the law of diminishing returns that kicks in when engineers turn off their creativity and instead look to make systems ‘better’ by adding more of what they’ve already done. Eventually, if the absence of creativity is allowed to continue for long enough, the world begins to bite back. It bites back by bringing in a bunch of negatives. These negatives progressively outweighing the benefits of adding more. To the point where a point of maximum viable (or sensible) complexity is reached. This is hopefully the time that the engineers wake up and realise that they now have a different job to do, that they need to increase the capabilities of the systems they’re tasked with creating and decrease the complexity.

With razors, sadly for customers, that point of maximum complexity occurred probably somewhere around the three-blade mark, and had entered the world of the surreal by the time 5-blade designs hit the market. The less said about the 7-blade versions probably the better. Imagine having to come in to work tomorrow morning to start a new razor project only to find that ‘the answer’ your boss has decided involves adding yet another superfluous and problem-creating blade.

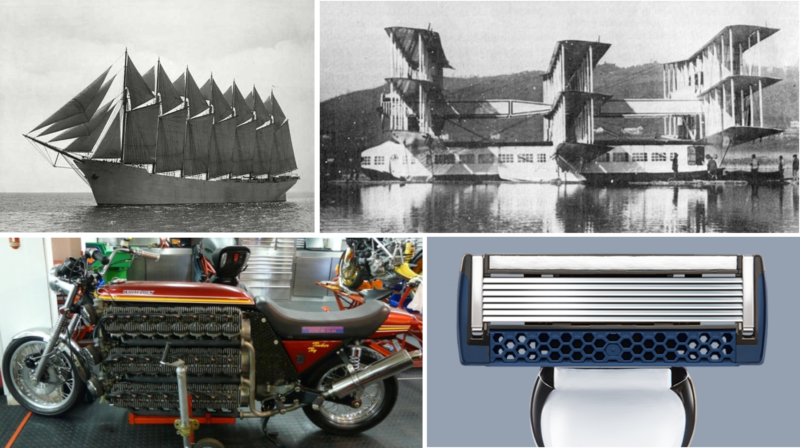

Still, could be worse. You could’ve been working for the boss that thought adding a sixth mast to the Thomas W Lawson schooner was a good idea. Or the bosses at Caprioni that believed the new Ca.60 project would benefit from adding a ninth wing. Or the bosses at the Whitelock Tinker Toy bike company, who thought that what the world needed was a bike with a 48 cylinder engine. Make that 49, because it also turned out the bike needed a separate engine to start the main engine. I daredn’t ask what was used to start the starter engine.

Somehow, it feels like some of the pages have fallen out of the Book of Common Sense. The page with this picture in it especially:

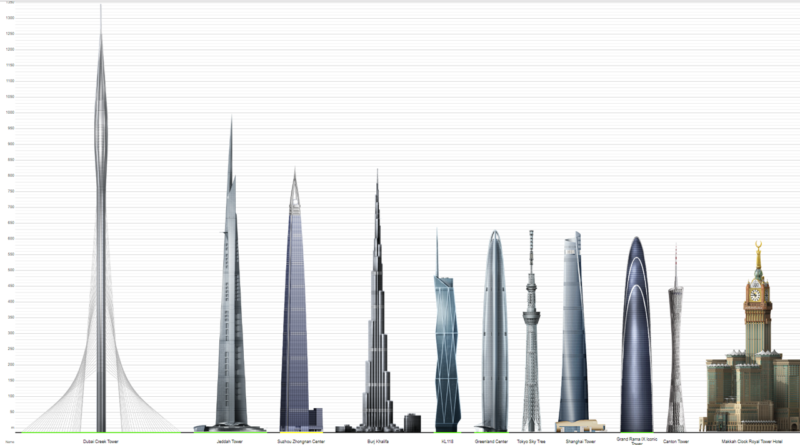

Not quite the same as the Mono-Bi-Poly Trend, but very definitely a close relative is the boss-loved concept of ‘bigger’. This Trend is perhaps most visible in the world of architecture. Probably in no small part because architects tend to have much bigger egos than engineers. Seemingly every architect on the planet aspires to work on a ‘world’s tallest building’ project at some point in their career. Especially those living in countries where the amount of disposable money has exceeded brain power.

Intelligence aside for a moment, one of the great things about these ‘my building’s bigger than yours’ pissing contests is they allow the engineers to switch on their creativity. Literally anything is possible if you think about it hard enough. So, if the architect wants a 1300m high tower, and the client is dumb enough to stump up the cash, why not?

Never mind the fact that, physics being the awkward thing it can sometimes be, the end result looks utterly ridiculous, and the support structures take up the same amount of land as a dozen more sensibly proportioned buildings. These kinds of project require some fairly delusional economic thinking. Like kidding yourself the final building will be a tourist attraction, and that the revenue earned allowing tourists to travel to the top will somehow offset the price of a window-cleaner.

Architects are worst, but aerospace engineers have often showed themselves to be not so far behind. And again, what engineer wouldn’t want to work on a ‘world’s biggest’ plane project? Especially since they have quite literally no skin in the game. The boss wants a plane that can carry 850 passengers? No problem, we can do that.

The bosses also, it turns out, have no skin in this game. And so when the politicians come calling for a piece of ‘statement’ technology, they’re also happy to play the game. Far easier than turning around and telling the truth. Like, revealing that the economics of big-ness only make sense up to a certain point. Carrying 850 passengers at a time is good for lowering seat-mile price, but only if you ignore all the awkward peripheral parameters. Not least of which being, working out exactly how many routes can sustain that level of traffic.

It’s a fine line between ‘statement’ technology, half-science economics and stupidity. The case for the Airbus A380 was always a marginal one. But because there was literally no-one with any real skin in the game when it came to deciding whether to go ahead with the project, it went ahead anyway.

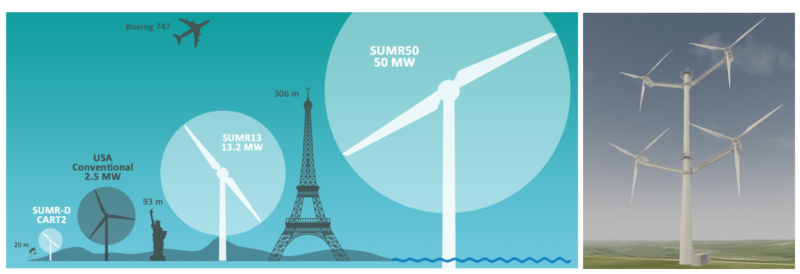

The desire of economies of scale naturally push all systems towards these kinds of giantism boundary. And, tragically, if there’s no-one willing to cry foul, it’s also highly likely that things will be allowed to sail blithely through the boundary and into the land of dinosaurs. Now that the industry has become ‘big business’, we can also see this boundary looming in the world of wind-turbines. Or rather, with the Sandia announcement of a 400m diameter, 50MW turbine, the industry has allowed itself to crash through the boundary with a flourish that is quite likely unprecedented. Unless, of course, we also include the Vestas project to ignore the rules of the Mono-Bi-Poly Trend and assemble multiple turbines on the same tower.

Here we see the precise same one-eye-closed economic logic at play. Bigger is more efficient, so bigger must be better. Well, it is until it isn’t. People – investors and politicians mainly – look at highly disguised data that shows all of the economy-of-scale upsides while conveniently not being shown (and, one suspects, they wouldn’t want to see it anyway since many of the inevitable downsides won’t become apparent until they’ve sold on their stake to an even more naïve downstream sucker) all the awkward and uncomfortable real world effects that also need to be taken into account. There are a thousand-and-one ‘yes, buts’ when it comes to proposing the world needs a 400m diameter off-shore wind-turbine – that the structural loads increase as the cube of the diameter, that the storm-forces on the structure increase with the square of the diameter, that the ‘out-of-sight-out-of-mind’ offshore location makes a terrific terrorist target that now necessitates constant surveillance – all of which ingenious engineers will be able to solve. But being able to, and deciding we should are two different things. Vastly different. Especially when there are so many other far more useful uses of that ingenuity. Which probably brings us back full circle to that Book of Common Sense again. And knowing when we’ve crossed the fine-lines between ego and truth, giant and giantism.