Most Suggestion Schemes fail. Most fail dismally. The wasted effort is sad. But not nearly so sad as just how predictable the failures are. We’ve had a few jobs in recent times to advise enterprises on the introduction of a new Suggestion Scheme. Or (worse still) a Dragon’s Den/Shark Tank type innovation competition. Mostly, our advice has been either ‘don’t do it’, or ‘if you insist on doing it (or, more likely, if your boss insists you do it), make sure you present it in such a way that participants know it is merely a bit of fun, and that you’re ready to receive some ‘shooting the messenger’ flak from your boss.

We’re over-simplifying, of course. Answering questions like should we have or not-have a Suggestion Scheme comes attached to a minefield of dependencies. Ditto how many people to involve; what you want them to do; when you want them to do it; what you need management to do, etc.

Fortunately, we know what a lot of those dependencies are these days. Thanks to a longstanding programme of research to decode what works, what doesn’t work, when it works and when it doesn’t.

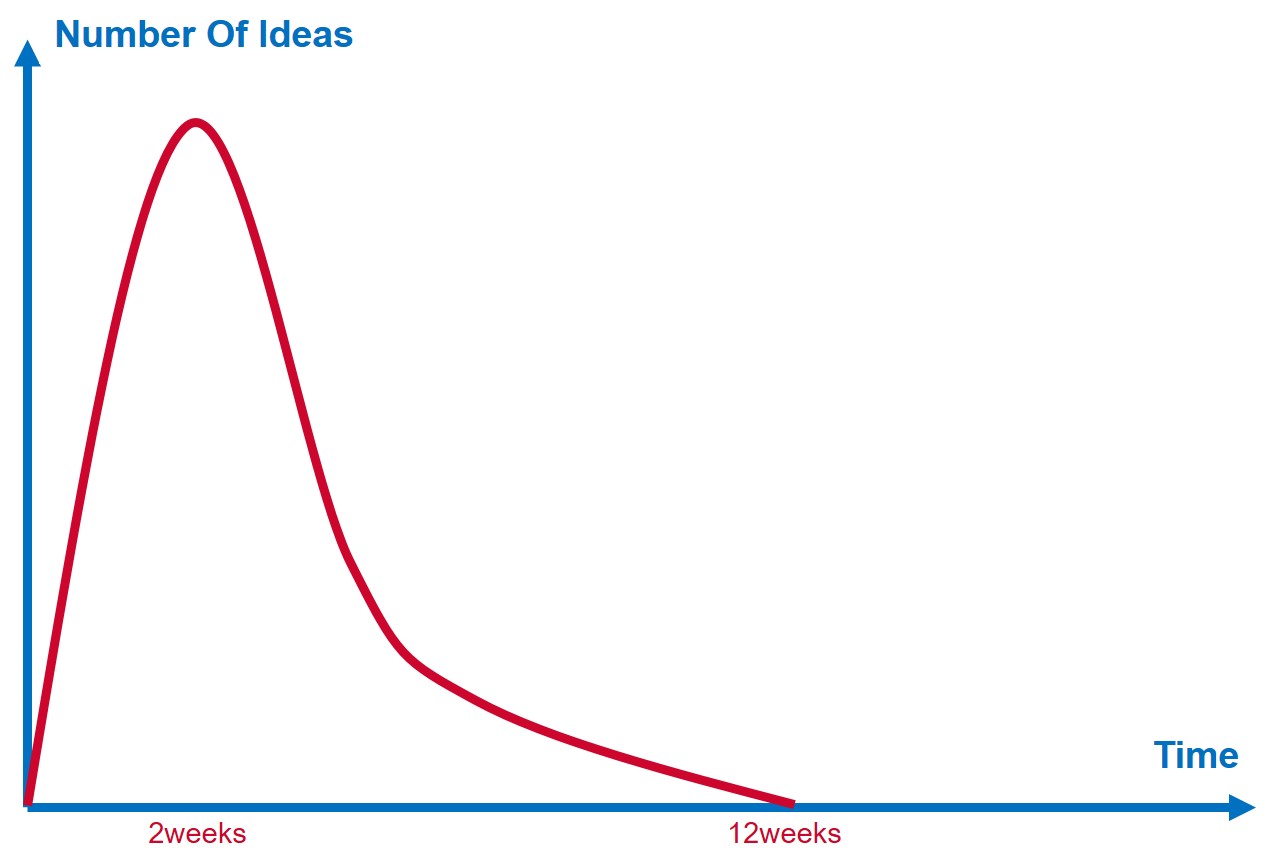

First up, a couple of universals. If it’s the first time an enterprise is considering having a Suggestion Scheme (alarm bells should already be ringing!), then what we know will happen is a massive backlog of frustrations will be unleashed. Lots of suggestions will arrive. The flood will continue for a while, but after it peaks there will be an initial sharp decline followed by an ever-slowing trickle down to an embarrassed zero. Something like this…

…which, if it looks like the first half of the Hype Cycle curve, is probably no coincidence. A trigger followed by a ‘peak of over-inflated expectations, followed by a ‘trough of despondency’, followed, if matters aren’t corrected, into a lonely, curled-up-in-a-corner death.

Second universal: the Law of ‘Try Again’. When the dust has settled on the previous failed Suggestion Scheme attempt (and very likely when there has been an (in-)appropriate change of personnel) it is time to try again. The resulting idea-count curve will look the same. Only the peak will be lower, and the death will come sooner. This trend will continue in a patter of ever-decreasing circles each time there is a new iteration.

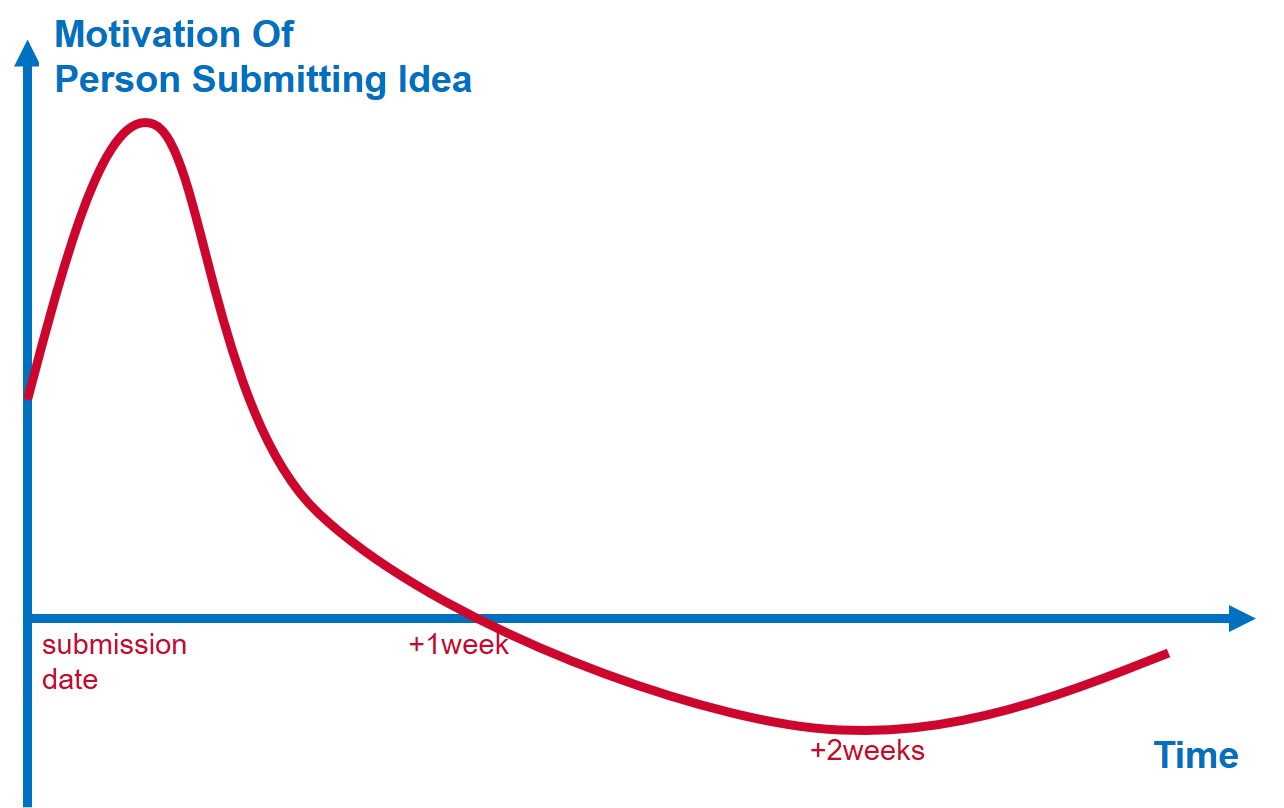

There are many reasons why Suggestion Schemes fail, but two stand out. The first relates to the amount of time it takes for management to respond when a person submits a suggestion. Here’s another curve…

…it too looks a lot like the Hype Cycle. The vertical axis this time is about motivation of the person that’s just taken the brave decision to submit an idea. What the graph basically says is that if that person doesn’t get some feedback on their idea within a week, their motivation is effectively disappeared; if they don’t get feedback within a fortnight, their idea-submitting motivation has dipped below zero. Which effectively means they now see the Suggestion Scheme for the joke that it is. Not that it was ever funny.

The second reason for failure flips us to the management side of the equation. No-one – managers included – comes to work intent on doing a bad job. No manager sets out to de-motivate the people that work for them. The reason it ends up happening is because few managers understand the vonClauswitz ‘critical mass at the critical point’ rule. Which, in Suggestion Scheme terms means, if you need to respond to the suggestions that arrive into the Scheme within a week and there are only so many people able to provide that feedback, then that is the critical mass. If the critical mass isn’t capable of handling all the suggestions in a timely fashion, the critical point can’t be ‘every employee’. It’s only possible to launch the scheme, in other words, to the size of population that management can reliably respond to within a week.

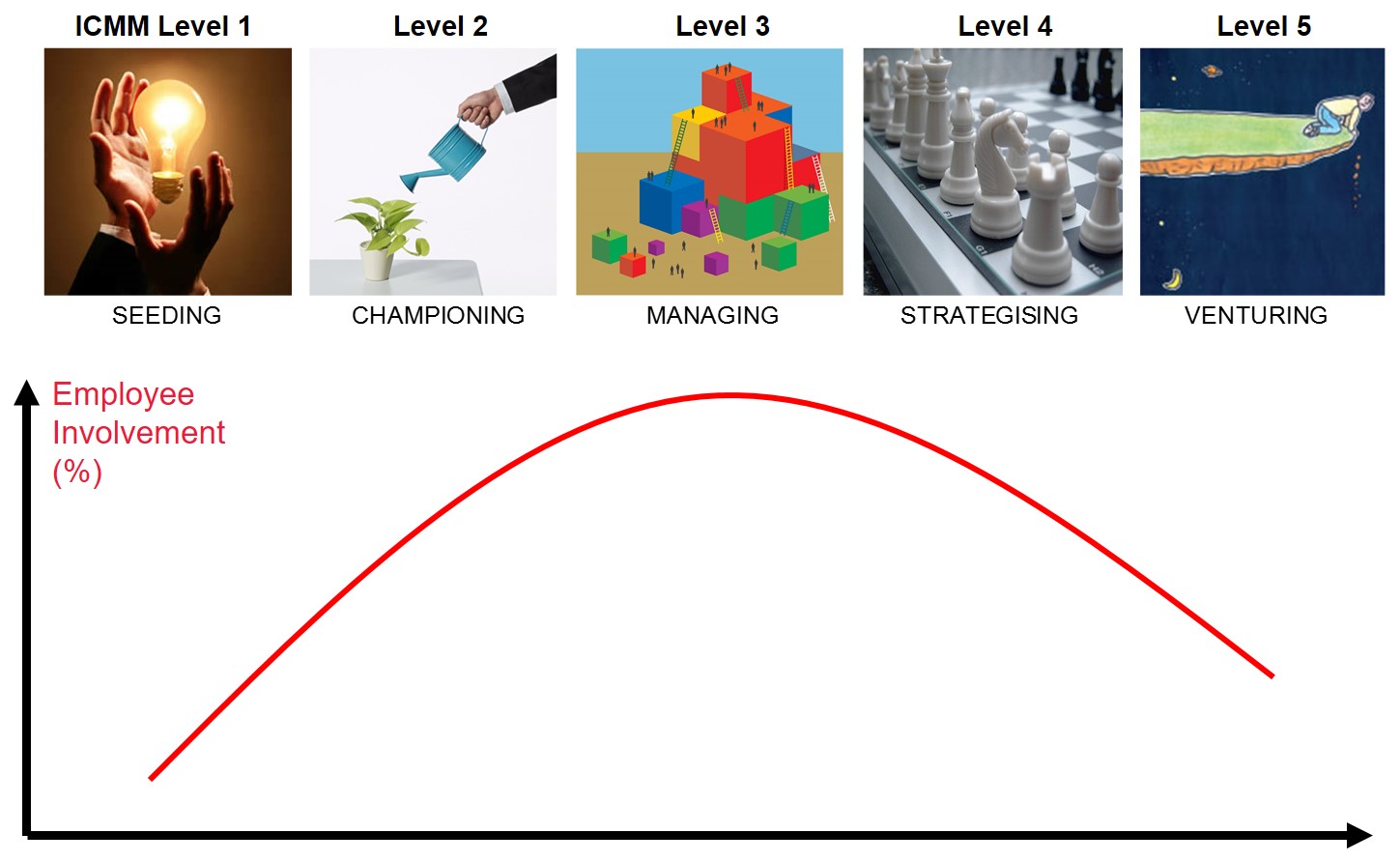

This in turn requires us to think about a final ‘universal’: Innovation Capability Maturity. The type and size of Suggestion Scheme an enterprise might consider deploying, also depends crucially on the Level of Capability of that enterprise.

There are currently five distinct Levels in our Innovation Capability Maturity Model (ICMM). Each requires a different Suggestion Scheme strategy, with different objectives:

| ICMM Level | Primary Objective | Key Contradiction | Key Success Driver |

| 1 | getting anybody to buy-in | lack of trust | creating a ‘sense of progress’ – real success stories (size immaterial) |

| 2 | getting anybody to stay in | insufficient (time) resources | releasing time from day-to-day work to explore improvement ideas |

| 3 | getting everyone to buy-in | suggestions get stuck at silo walls | cross-functional teams and KPIs |

| 4 | getting people to suggest good questions rather than answers | “a good question is worth a thousand answers” = undoing lots of previous suggestions | good questions = contradictions, customer outcomes (tangible & especially intangible) |

| 5 | achieving requisite question/answer ratio | prioritisation of questions and their multitude of answers | embracing complexity, surfing the edge of chaos, and emergent markets |

Taken all together, the very likely connection between ICMM Level and the number of employees productively engaged in Suggestion Scheme activities will tend to look something like this:

Which means a Level 3 organisation like – all-time classic Suggestion-driven culture – Toyota will have everyone engaged in submitting and implementing improvement ideas. Versus a Level 1 organisation (i.e. most organisations on the planet), which really ought to have a much lower (‘critical mass at the critical point’) proportion of people asked to submit suggestions. But then also versus what we might expect to see in a Level 5 enterprise (of which there are probably, realistically, two or three on the planet), where there’s a living realisation that questions are much more important than answers, that important questions require a lot of time and effort to answer, and that the real trick in life involves understanding and embracing complexity – understanding how the world works at a ‘First Principles’ level, and looking for non-linearities in which small inputs create non-linearly spectacular outcomes.

Welcome to the machine.