‘Sheep in Fog’ is the metaphor I’ve been carrying around for a while now when I look at the innovation activities taking place – or not taking place – within a majority of organisations around the world right now: very little bravery and even less direction clarity.

It’s also, as it happens, one of my favourite poems by Sylvia Plath. Well, ‘favourite’ is probably too strong a word. ‘Admire’ is probably better. The poem is overwhelmingly bleak and I’m only glass-half-empty-level bleak. I’ve always read it as a list of metaphors describing how she felt about the world at a particularly difficult time in her life.

Only lately have I come to connect my innovation metaphor to the poem. The more I think about the connection, however, the more I think Plath’s words tell us about the ‘Hero’s Journey’ from an innovator’s perspective. Four things stand out for me.

First, she uses personification – the stars ‘regard me sadly, the train has ‘breath’, and the fields ‘threaten’ her. All of this creates a sense that nature pities her, or finds her presence problematic. She does not belong in it. Plath as the prospective innovation Hero, and nature as the ‘efficiency engine’, everyday world she unwittingly finds herself in.

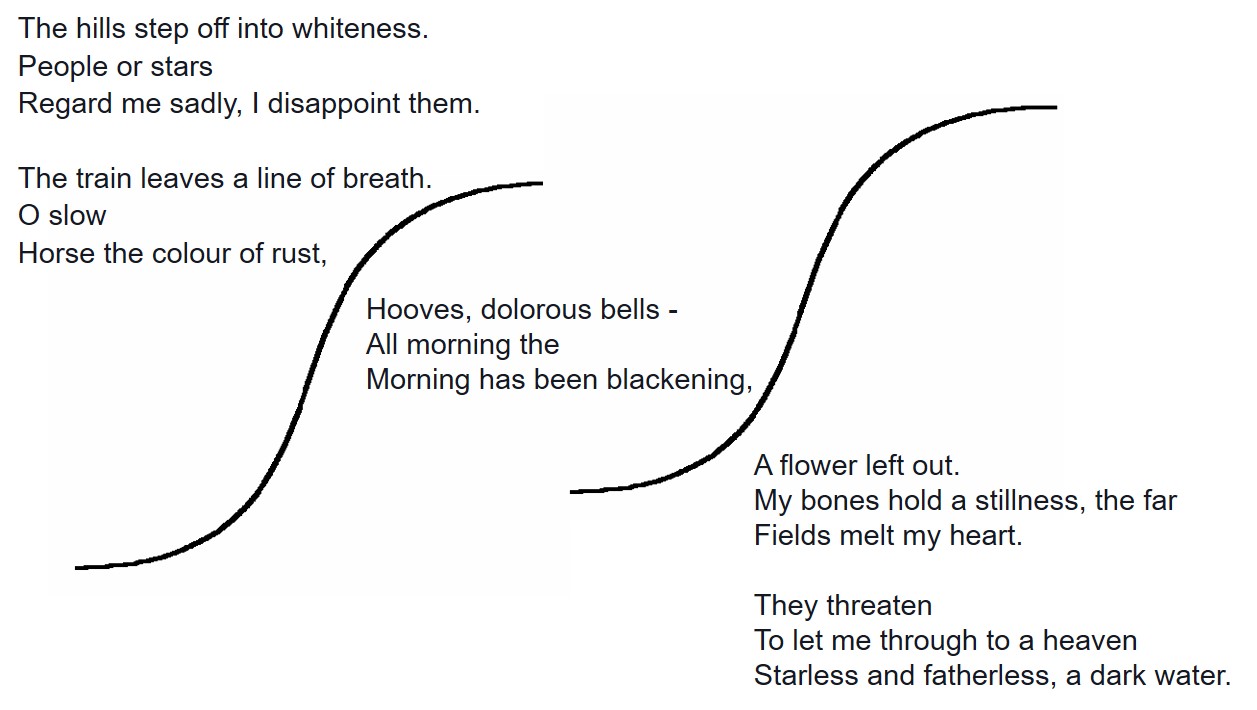

Secondly, she uses enjambment, a poetic device in which a single sentence is broken across two verses. Her discussion of the horse in the second stanza extends into the third, while the discussion of the morning is split between the third and the fourth. The technique is used to great effect in the poem to link all of the disparate metaphors together to create a profound sense of estrangement and uneasiness. While I’m sure Plath had no overt conception of s-curves and the idea of the innovator as the navigator between one s-curve and the next, it feels that, somehow, instinctively, she did. The enjambment makes an awful lot of sense, in other words, as a representation of the discontinuous jump between the current world and the next:

Thirdly, the title of the poem references how Plath (the ‘innovator’) feels – a lost sheep wandering in a murky and meaningless world. She feels like she continually disappoints those around her, all while she sees the world blackening. There is a clear paradox here in that she calls this terrifying place a ‘heaven’. This dark, fatherless heaven was used by Plath as a telling metaphor for her personal life, but perhaps it makes for an even more powerful metaphor to represent the ‘Ordeal’ of the Hero’s Journey? This ‘dark heaven’ is the Contradiction.

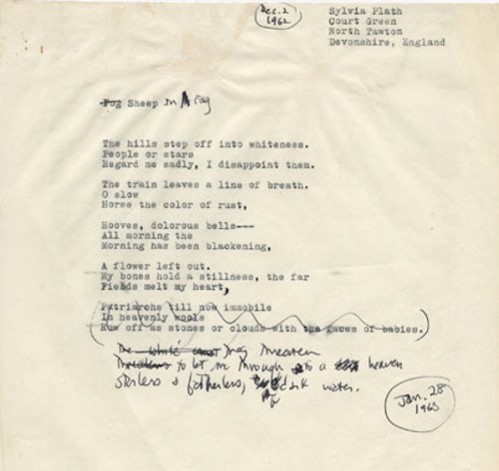

The Hero’s Journey stage connection follows, too, fourthly, when we step back and connect the poem to Plath’s life. Plath didn’t prevail over her Ordeal. In the Hero’s Journey, after the Ordeal, something has to die. Plath killed herself a month after the final changes she made to the poem. She never made it out of the fog. In this regard, the poem is certainly bleak and hopeless. But then again, perhaps, all the more sophisticated because it captures, in a very few lines, a profound ambivalence towards death. It is in this regard too, I think, a telling metaphor for the life of the innovator, and the (98%) likelihood that the innovation-sheep don’t make it out of the fog either.

Call it a warning. Or a roadmap. Or, maybe, just a call to arms.

In that regard, finally, I find much to think about in the final changes Plath made to the original draft of the poem in those final weeks of her life: