For every complex problem, there is a clear, simple, wrong answer. As the UK swiftly follows the US, Hungary, Poland, Brazil, Turkey, The Phillipinnes and others down the slippery slope of political populism, it is rapidly becoming clear that it is eminently possible to have a democracy in which the liberal rights of the individual tend to zero. Similarly, in many ways a large part of the Brexiteer argument against the EU, it is also very possible to have highly liberal institutions which are at the same time highly un-democratic. Achieving liberal democracy, in other words, is quite difficult. It is difficult because – counter-intuitively – ‘liberal’ and ‘democratic’ are in conflict with one another. This is the essential premise of Yascha Mounk’s already-classic 2018 tome, ‘The People Versus Democracy’. The premise builds on Mounk’s attempts to restore the original definitions of the two words:

Democracy: a set of binding electoral instruments that effectively translates popular views into public policy.

Liberal: effective protection of the rule of law and guarantees of individual rights such as freedom of speech, worship, press, and association to all citizens.

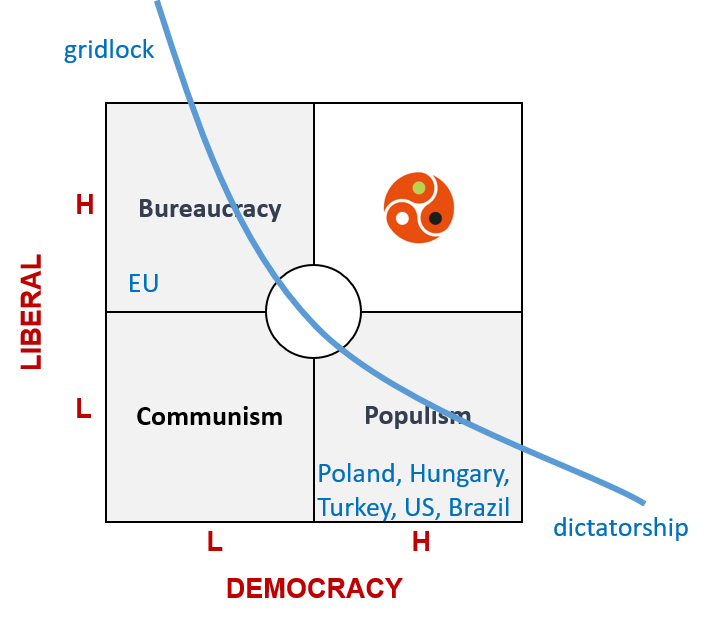

Under these two definitions, and a clear me/we conflict becomes apparent. In that, what ‘we’ collectively want as a society is rarely the same as what ‘I’ might want individually. Taken together, we can draw a liberal-democracy 2×2 matrix looking something like this:

This is the sort of picture I’ve normally found to be quite re-assuring. It means that if we wish to get the best of both worlds – liberal and democratic – we need to solve a contradiction, and, if we want to solve contradictions, there’s no better way than through using TRIZ and Systematic Innovation.

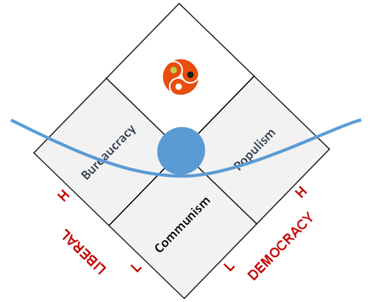

The other, perhaps more subtle, ‘re-assuring’ part of the picture is the blue either-or line, which, if we angle the matrix a few degrees begins to look something like this:

… a blue ball sitting at the bottom of a bowl means – re-assuringly – that the further we try and move the ball left or right, the more the walls of the bowl try and bring it back to the middle again. While we might not be totally happy with the ball sitting at the bottom of this bowl, it is an awful lot better than being at the extreme edges of the bowl. The shape of the bowl is such that the whole system is stable. The more things try to move to an extreme, the more surrounding forces seek to return matters to the middle.

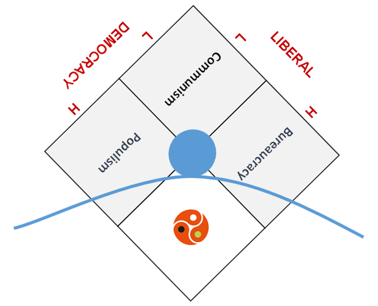

I now see, however, that my re-assurance by this stable-bowl model has not been well-founded. What Mounk’s book has taught me is that today the ball and bowl actually look more like this:

In this view of the world, the ball is very definitely not stable. As it nudges left or right of centre, it is more and more likely to keep going. The extremes, in other words, become not only much more likely, but actually inevitable.

My image of the bowl orientation has been wrong. Or, perhaps (no-one likes being wrong!), the self-stabilising bowl has somehow managed to become inverted. I’m still not sure which of the two is right, but I’m pretty certain that a lot of the societal feedback loops that helped the bowl stay upright and thus make the ball stable have recently, thanks to social media, Fake News and the deliberate (Russian) de-stabilisers of the world, disappeared or become perverted. Extreme-avoiding negative feedback loops have now become highly unstable positive ones. Just as in the pop-music charts, where the higher up the charts a song is, the more it is likely to be played on the radio, and so even more people go out and buy it, extreme politics increasingly begets even more extreme responses.

I’m too late I know, but I really hope that when UK citizens go to the polls this coming Thursday they take with them even the faintest inkling that a vote for a populist politician or party is a vote for massive instability in the coming months and years.

Anyone that knows me knows that inside my gruff glass-half-empty exterior is an equally gruff but nevertheless glass-half-full interior. Deep inside, I remain confident that there are always winners even during the biggest, fastest slide down the slippery slope and off the slippery cliff, but, boy, on the outside, I’m starting to wish I had a lot more fingers I could cross.