At the risk of beginning to sound like a broken record, here’s another rant about Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s apparent either/or worldview. In that world, people have either got ‘skin in the game’ or they don’t have skin in the game: they’re either good or bad. In this way journalists, academics, bankers, lawyers and politicians all fall on the bad side of the line and artisans, entrepreneurs and suicide bombers all fall on the other.

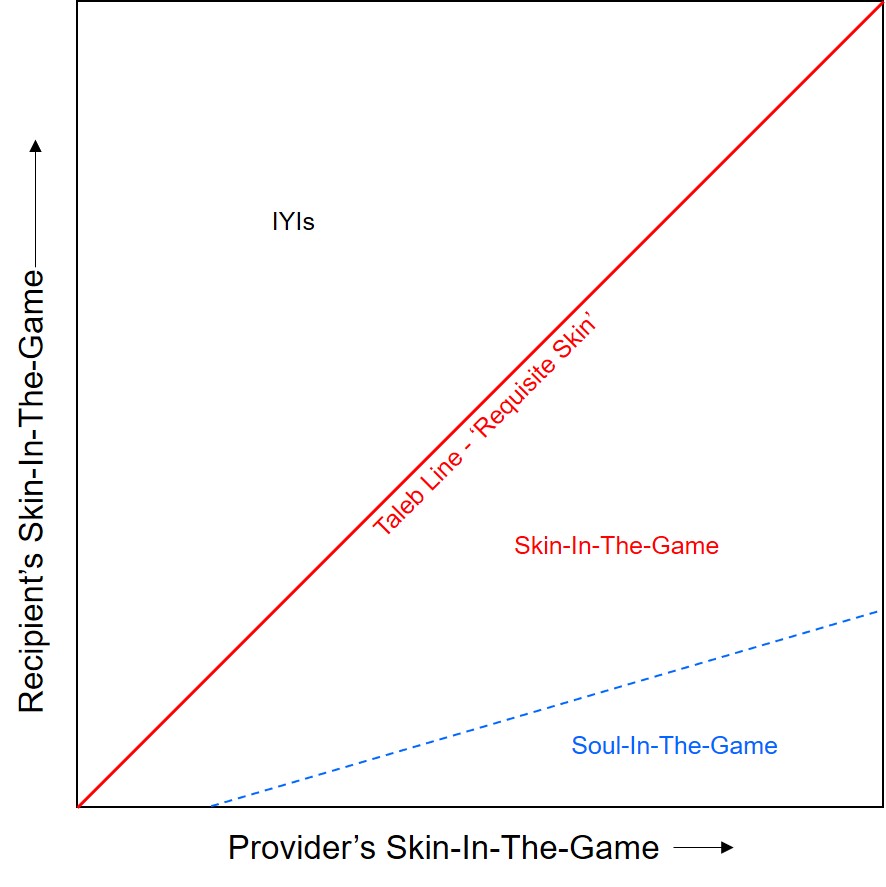

To overcome the futility of either/or debates, I thought it might be a good idea to create some kind of a skin-in-the-game landscape. Drawing such I landscape, I figured, might be a way to capture the relative amounts of skin that different professions might have, and the relative amount of skin the people listening to them might have. Here’s the basic idea:

One of the things that I see causing the most push-back to Taleb is the view that all of us have, to some extent, skin in whatever games we choose to play. In that if we do something bad, at work for example, there is the possibility that we lose our job and therefore our source of income. That said, some professions are more likely to sack wayward employees than others. Journalists live on a fairly precarious employment knife-edge these days, whereas few if any bankers or lawyers find themselves out of work as a result of their mistakes. Any sensible skin, landscape, therefore needs to relativise skin in some way. The landscape image attempts to do this via the diagonal ‘Taleb Line’ or ‘Requisite Skin’ line. The idea behind this line is that if I’m advising a client, the amount of skin I possess in my game should be proportional to the amount of skin the client expose themselves to by following my advice. If my bad advice risks N% of the turnover of the client’s enterprise, if I have requisite skin in the game, I should risk N% of my annual income as a sign to the client that I believe in what I’m telling them to do. Above this line means the client’s risk is proportionately greater than mine; below the line and my risk is proportionately greater than theirs.

The figure also allows for Taleb’s acknowledgement of a third kind of person, down in the bottom right hand corner of the landscape, the (relatively rare) individuals with ‘soul in the game’.

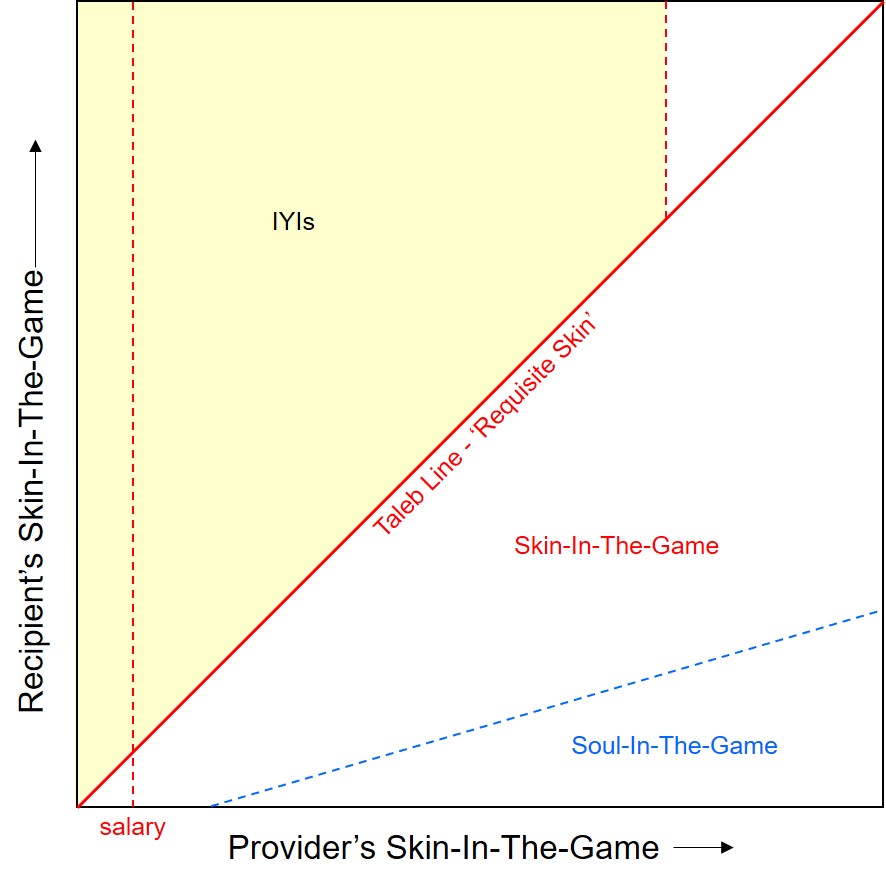

The next thing we can do to continue the relativisation journey is to add in a couple of vertical lines. The first one indicates the skin associated with a person’s salary. The second one, set at a much higher level of skin in the provider’s game is a (perhaps hypothetical) level of skin beyond which no individual or provider organisation could hope to match the skin commitments of the recipient. The thinking here is that there are certain capital-intensive construction or infrastructure projects that can only be afforded by recipients capable of mitigating their risks by means other than those coming from the provider. Of the two lines, the salary line is probably the more important one in terms of hopefully helping to answer the complaints of Taleb detractors.

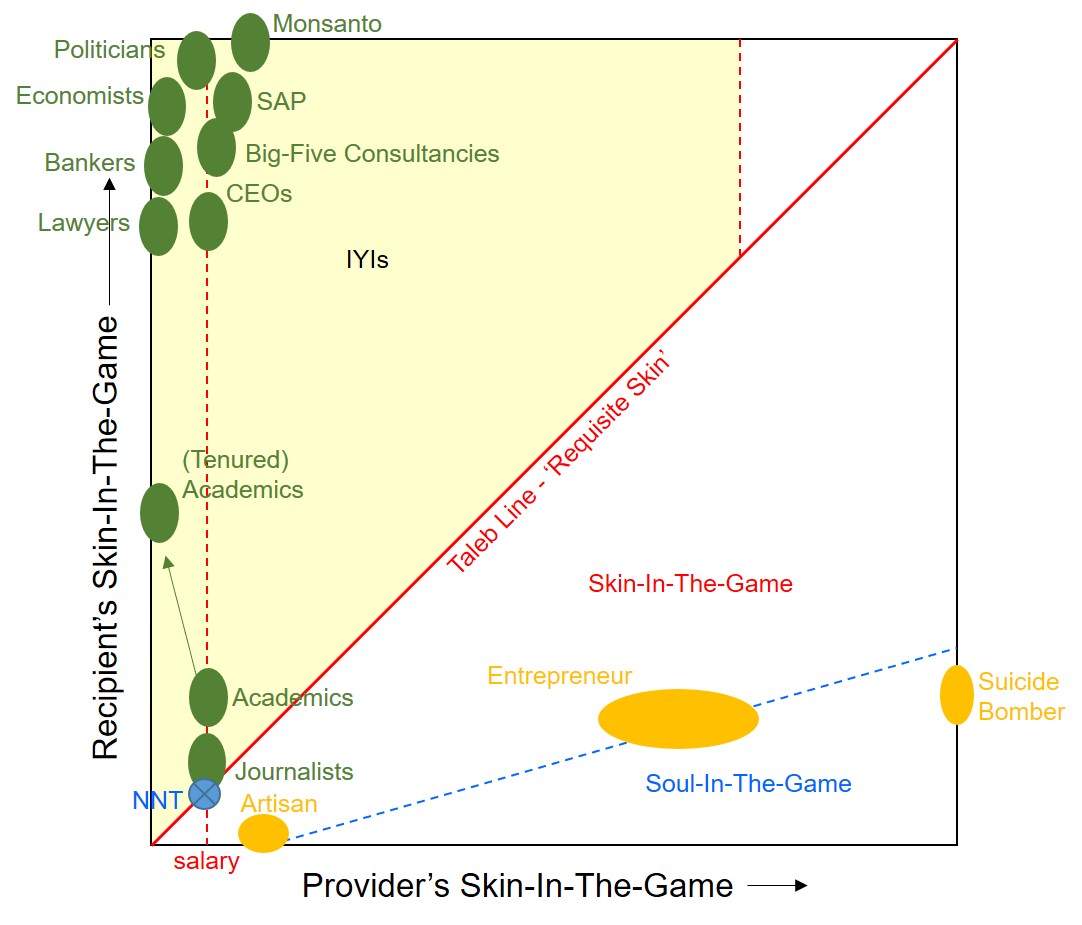

Now we have defined the landscape, we can start adding a few data points to it. In this next image, in green, I’ve tried to pick out one or two of Taleb’s Intellectual Yet Idiot (IYIs) victims, plus one or two of my own. And in orange some of Taleb’s ‘do have skin in the game’ heroes. Or maybe, in the case of suicide bombers, not so much ‘heroes’ as ‘people with a very high level of soul in their game’ (which is why the problems they’re associated with are so difficult for society to resolve). Finally, for good measure, I thought I’d add Nassim Nicholas Taleb himself (blue dot) onto the picture:

Looking at this populated landscape, I think, reveals a somewhat different picture of who the criminals and heroes in modern society are. Criminals in this sense being the people on the top left corner, furthest away from the Requisite Skin line, the people that have the least skin in the game and the recipients of their spoutings have the most to lose.

Most interesting to me is that this picture places Taleb pretty close to one of his favourite targets, journalists. It’s often said that the people we bear the most anomisity towards are those closest to ourselves, and this picture seems to bear that out. Taleb is not far off a journalist himself. He might earn more than most, but once we relativise everything to salary units, he’s pretty much exactly the same. He’s a self proclaimed ‘flaneur’. The same as the better journalists. Taleb’s only real advantage over them being he understands better how the world works at the first-principle level, and he’s had skin in multiple games.