I’m having a quiet week. In theory spending my time doing physical labour in the garden, but in practice looking for excuses not to. Enter an academic Twitter troll. Perfect.

The resulting correspondence is too boring to repeat here, but, needless to say, it was prompted by me prodding at academics doing pointless research.

The UK is still somewhat reeling from the pre-Brexit Referendum that people have had enough of experts. Which means this is a particularly testing time to be an expert. The answer to the contradiction – ‘we want experts and we don’t want experts’ – include, a) a recognition that not listening to experts anymore is not to be equated to a demand for blind ignorance (as we are seeing three years into the still-not-over Brexit debacle), and b) that our definition of experts needs to be updated.

The large majority of so-called experts, and nearly all experts of the academic persuasion, are specialists. They have lots of vertical knowledge, and, too often, not enough horizontal, inter-disciplinary knowledge. In a world as complex as the one we now all inhabit, this lack of horizontal knowledge becomes a bigger and bigger problem. In complex systems, its not so much the ‘things’ that are important as the relationships ‘between’ the things.

What we know from the last twenty years of our innovation research is that 98% of innovation attempts fail. Ten million case-studies into the subject, we now know some of the core characteristics of the 2% that were successful that were not present in the 98% of prospective innovators that failed.

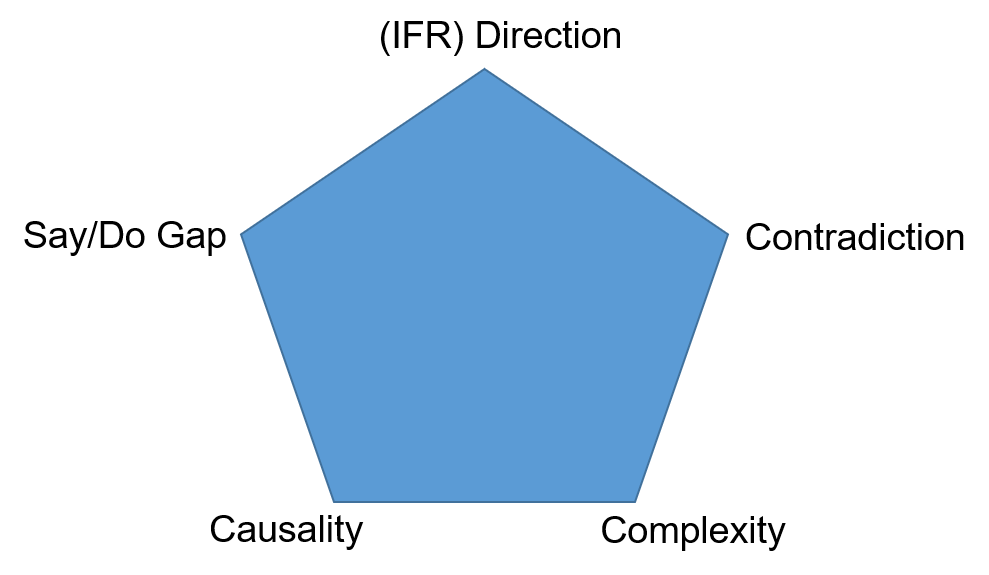

The 2%:

– Had a clear (Ideal Final Result oriented) direction

– Understood the importance of revealing causal (as opposed to merely correlated) relationships

– Understood the importance of revealing and resolving conflicts and contradictions to eliminate trade-offs

– Understood the characteristics of complex adaptive systems

– Understood the often considerable gap between what customers say they want and what they subsequently spent their money on

‘Research’ may be seen to have a variety of different purposes, but in almost all cases, the work being undertaken is a precursor to some form of innovation. We research to enable innovation.

If we accept that to be the case, then the above five Innovation ‘DNA’ strands also extend to the world of research.

A big part of our ongoing Systematic Innovation research involves trawling the various worlds of human endeavour. Our biggest source of data still comes from the global patent databases. The second biggest is the academic literature.

Taking on the job of sifting through all of this apparent ‘knowledge’ with the limited resources available to us very swiftly forced us to develop heuristics that allowed us to find what we now know to be the relatively rare needles in the global knowledge haystack. It was the imperative to solve that contradiction that enabled us to reveal the innovation DNA. Now we know it, it enables us to eliminate about 85% of the patents that are granted (97% will never make any money, but a somewhat bigger percentage have some contriadiction-solving merit worthy of sharing with others). As far as academia is concerned, it allows us to eliminate around about 98% of all of the academic literature.

On one hand the lack of relevance of the vast majority of academic output makes our job rather easy. On the other, from a value-for-money perspective it is, I think, a fairly damning indictment of the current academic system. Academia used to be the place to go if a person wanted to work at the frontiers of mankind’s understanding of the world. But once the world started evolving faster than academics and their desire to do everything in PhD-size three-year chunks, then a problem began to arise. The problem was especially great if you were a person tasked with innovating. And so, as is always the case, necessity is the mother of invention. When those tasked with innovating got no joy from academia, they went off and did things themselves. And it turns out that enough of the armies of trial-and-error amateurs, flaneurs, sceptics, and frustrated, pig-headed ornery souls succeed to now make a literal and practical mockery of the academic world.

What I failed to get through to my temporary academic-troll was that this doesn’t mean that doing research is a waste of time or money. There have been enough of the flaneurs now to reveal the innovation DNA. Now we know it, it ought to be incumbent on any ‘expert’ working in the research and innovation domains to make use of it. Which means designing research using the DNA. Or designing research that challenges that DNA and seeks to deepen our collective first-principle understanding of the world.

It does not mean wasting precous resources doing research that doesn’t have a meaningful direction, doesn’t actively seek causal relationships, doesn’t look for or resolve contradictions, fails to embrace the complexities of the world, or fails to recognise that customers (and that includes academics) do things for two reasons – a good one and a real one. Academics, for the most part, it seems, understand the ‘good’ part, but are still for the most part it seems utterly clueless on the ‘real’ bit.