I think the final straw was being lectured by the editor of an academic journal on how to get a paper accepted in his august publication. It was like being back in a bad re-run of the 1970s. Academia is increasingly no longer fit for purpose. Certainly not when it comes to writing about innovation. Innovation happens elsewhere. And then – maybe – academia comes along and pontificates about what happened later. Academics are increasingly society’s historians.

This is a big pity because the world of innovation needs academia. But innovation means getting things out there, seeing what happened, learning from it, and trying again. No-one builds billion-dollar new products and services in one iteration. And it certainly doesn’t wait a year for referees to deliberate about the validity or otherwise about the latest iteration in the inherently complex innovation journey.

Worse still is TRIZ’s relationship to academia. Thanks to an accident of history, the original TRIZ research was not conducted by traditional academics. As TRIZ grew, it grew a completely separate mountain of knowledge. Which is a problem for TRIZ-sympathetic academics. The academic world works largely on citations. And so if an author isn’t able to cite something in the traditional academic world, it is highly likely their paper is going to be rejected by the traditional academic world. And there lies the rub. There’s barely anything in the traditional academic world’s mountain of knowledge that is of any significant value once a person knows TRIZ.

The TRIZ research has always been about distilling the world down to ‘first principles’. Which essentially means removing all of the failed innovation attempt noise and focusing instead on the signal coming from the 2% of attempts that ended successfully. Put more starkly, the tRIZ research tells us that 98% of traditional academic output is noise.

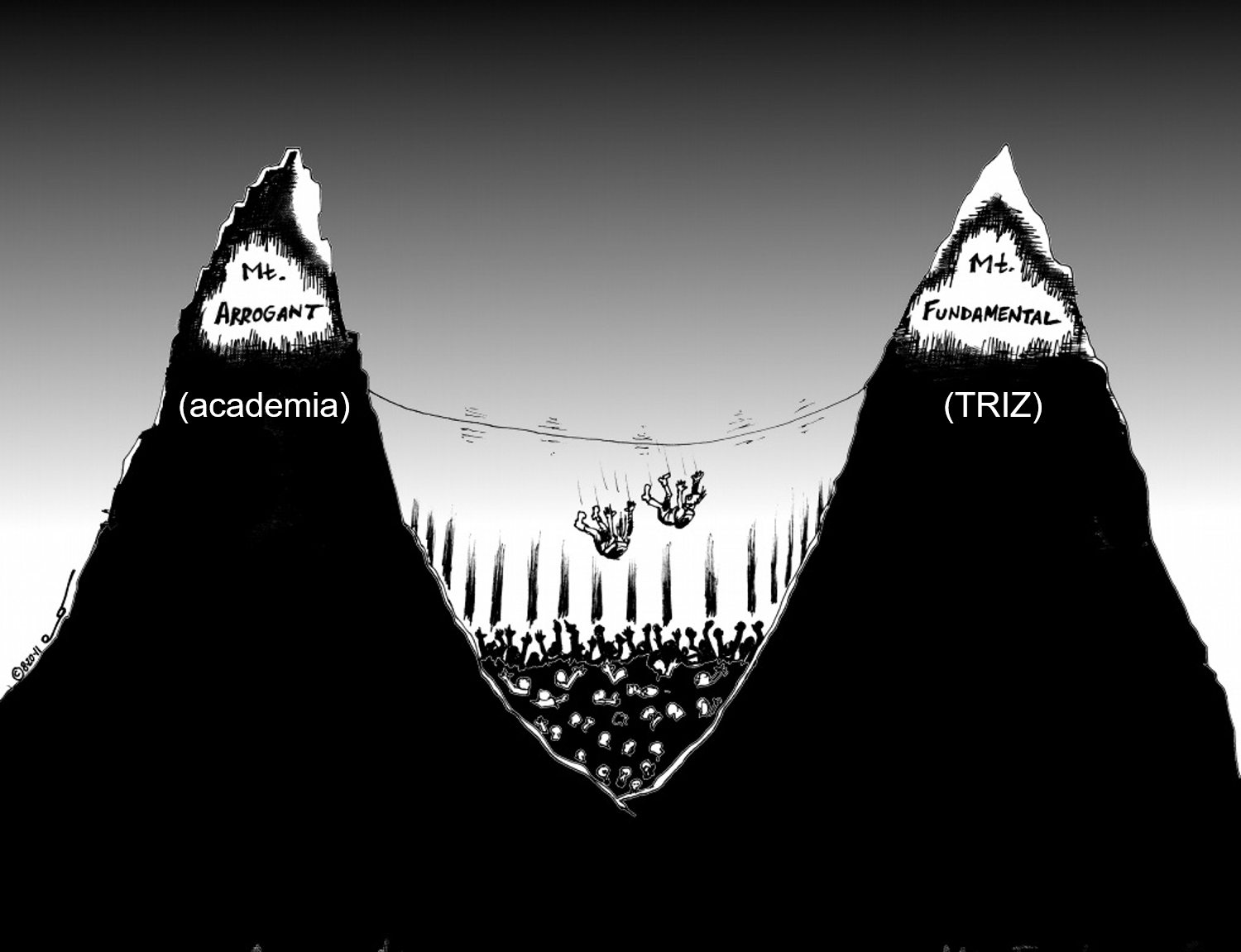

I often find myself showing the ‘two mountains’ graphic to try and explain the fundamental problem that the academic world has found itself embroiled in. Some – usually traditional academics – can’t comprehend how the two mountains are the same height. This is why I tend to label their mountain, ‘Mount Arrogant’, but, in fairness to them, I can see why they might be offended by the idea that a bunch or Soviet engineers might have accidentally uncovered what we now know to be fundamental truths about how the world works. In theory the academic world is all about ‘evidence-based’ knowledge acquisition. In practice, unfortunately, it is instead about Confirmation Bias and Wilful Blindness. Time and time again, TRIZ findings will tell a traditional researcher (or – worse – thir supervisor) that what they’re doing is dumb. Or has already been done by someone else. Or is looking in the wrong direction. No-one likes news like that. I get it.

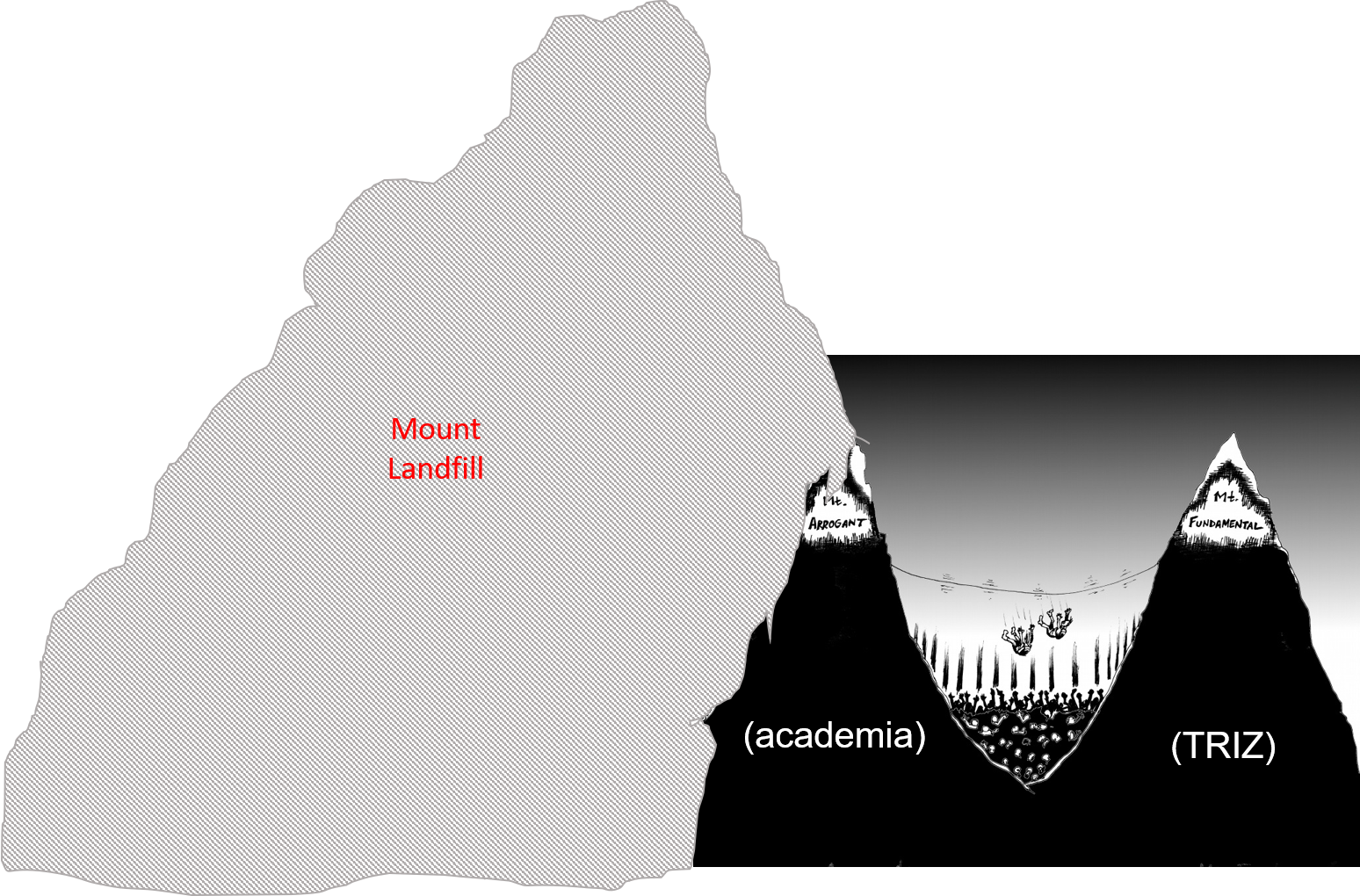

That emotional trauma, however, can’t be allowed to alter the fact that the vast majority of the mountain of knowledge built by the traditional academic world isn’t knowledge at all. It is instead largely the science of trade-off and compromise, the science of being stuck inside a silo and failing to make connections to research in other domains, and the science of ill-founded hypotheses. If we include all of these scientific mis-steps, then sure, the traditional academic mountain might look enormous. But once we look more closely – through a TRIZ lens – the large majority of that mountain is mere landfill.

This is a problem for the traditional academic world. But it is ultimately also an enormous problem for the TRIZ world. A world that needs to build bridges between the two mountains. And do so even though the people on the other mountain are more often than not busy cutting the ropes.

As the political world is increasingly demonstrating, people have indeed ‘had enough of experts’. But the world is also beginning to wake up to the thought that while ‘blind ignorance’, Fake News and ‘my-opinion-beats-your-fact’ memes might be alternatives, they definitely don’t improve matters.

The world needs academia, just not the one we currently have. Academia needs to wake up. The revolution is here. Three-year PhD cycles, two-year editorial procrastination cycles no longer make any kind of sense. Neither does having academics working on trade-off and compromise projects. John Boyd’s OODA loop work tells us the former is wrong; TRIZ tells us the latter is wrong. The academics that learn the fastest are the ones that will prevail. The world needs one mountain of knowledge not two. The academics that build the bridges are the ones that will prevail.