It feels like there are a million and one ways to define ‘inovation’, but the one we here in Systematic-Innovation-Land typically end up using is ‘successful step-change’. Simple enough, but still plenty to cause a deal of confusion when we try and apply it in a specific organisation. The main problem usually comes with the word ‘successful’. Probably because the word puts the onus back on the project team to define what success means to them. The generic idea at that point tends to distill down to some form of net value addition, but specifically, I would say that in nearly every case – certainly in the commercial world – we find ourselves deferring to the accountants in the room and their desire to see a positive Return On Investment: the ratio of the net receipts back from customers over how much money was spent to get there. Simple again. Except, it misses at least half of the story. ‘The most important numbers are unknown and unknowable,’ so said W Edwards Deming in his gruff attempt to get the accountants to wake up and recognize the presence of all of the emotional and intangible issues that inherently weave their way in to any innovation story.

Any meaningful measure of innovation success, I believe, needs to take due account of these intangible issues. I also believe that the late great Dr Deming was largely wrong when he declared they weren’t measurable. They’re merely more difficult to measure than stuff like dollars and cents.

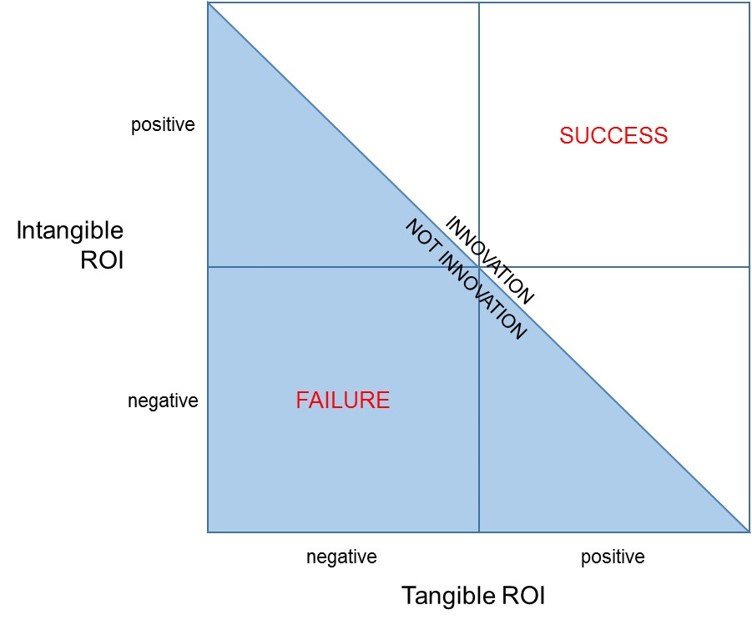

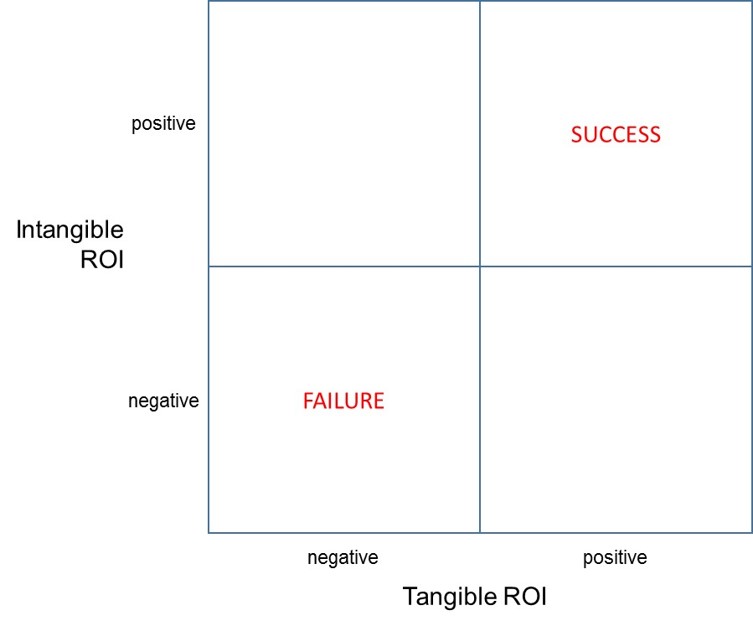

The simple act of allowing ourselves permission to contemplate the possibility that in the innovati on intangibles can be calculated should permit us to draw grids like this:

on intangibles can be calculated should permit us to draw grids like this:

Assuming it then becomes possible to somehow cross-calibrate and connect tangible and intangible ROI (a fairly big assumption, granted, at this point), it becomes possible to get a more complete definition of what innovation is: the boundary between innovation and not innovation corresponding to a diagonal line drawn from the top left to the bottom right of the grid:

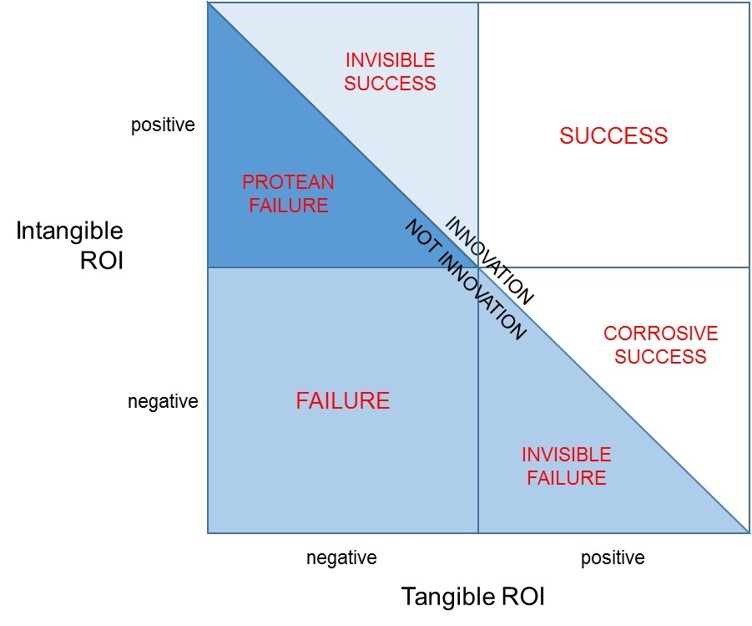

Everything above this line we can see is an innovation because the combination of tangible and intangible ROI is net positive, and everything below is not because the combination is negative. The diagonal line also allows us to think about and define four triangular areas. Here’s our current attempt to do that job:

Which nows gives us six possible innovation ROI scenarios:

Success (where we’d really like to be) – ROI from both tangible and intangible sources are both positive, and hence the success of the attempt is unequivocal.

Failure (where we really don’t want to be) – ROI from both tangibleand intangible sources are both negative: we didn’t win on either count.

Invisible Success – as in ‘invisible to the accountants’ – the project did not make a positive return against their tangible ROI metrics, but the intangible ROI actually turned out to more than offset the negative tangible figures. This is the innovation project we thought had failed, but once we took due account of all of the issues, we should actually have called it a success.

Invisible Failure – represents the converse of invisible success: this is a project the accountants and tangible figures told us had been successful, but sadly, after taking into account the negative ROI for the intanigbles, we should actually have described the project as a failure because our customers were emotionally worse off than before we turned up with our bright idea.

Corrosive Success – a situation where the tangible figures tell us we’ve been successful, but the ROI from the intangibles was unfortunately a negative number. Not so negative as to completely wipe out the tangible gains, but a corrosive problem because we got the intangibles wrong and therefore most likely planted some unfortunate negative emotion seeds in the minds of customers. Seeds like loss of good-will, loss of trust, ‘you trapped me in your eco-system’, etc, that make it much more difficult for the next round of innovators in the organisation to succeed.

Protean Failure – another segment that has to be seen as a failure, because overall ROI when we totaled up the tangibles and intangibles was negative, but we shouldn’t be totally de-moralised because we did actually get some of the intangibles right. And given that, right now, we all know far less about the intangibles than we do about the intangibles, in many ways we got some aspects of the most difficult part of the innovation story right. Which in turn is trying to get us to consider that a simple re-think in the way we presented our solution to the customer we might be able to get the project across the line and into the ‘innovation’ half of the picture. We use the term ‘Protean’ here in the sense that our best success strategy is to become fluid and adaptive (like the Greek God, Proteus) and experiment with different things until we find our winning ‘Plan B’.

So much for re-thinking how we define the ROI of an innovation project. It might be okay in theory to say that we can measure ROI in terms of the intangibles, the real test of the model can only come through a translation of that theory into practice. Which is where our PanSensic tools usually come to the rescue.

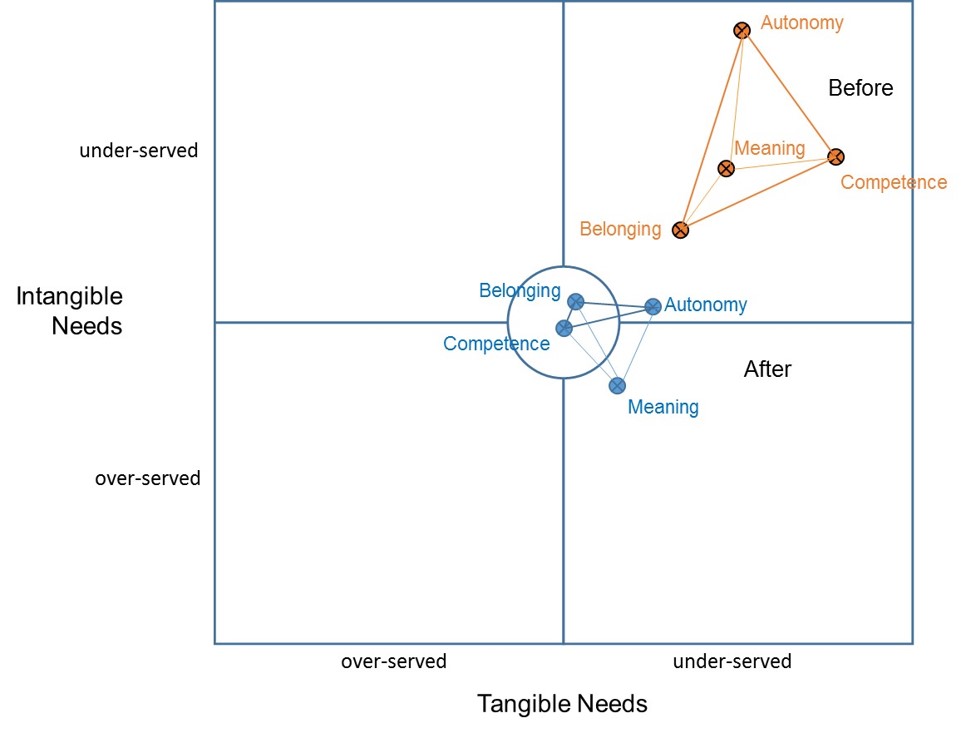

They have done so in this case as a result of a large piece of work to find ways of defining and plotting what we came to call the quartet of ‘human universal’ intangibles – Autonomy-Belonging-Competence-Meaning (ABC-M) – onto a map of frustrations:

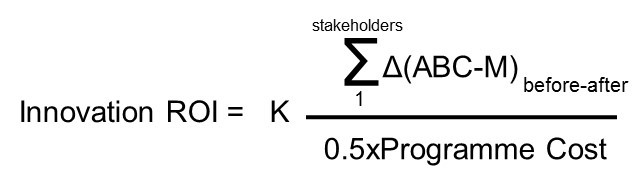

Although still not easy to calculate (see Systematic Innovation e-zine, Issue 146 describes how we do it), once we’ve found a way then we have a means to calculate the benefits part of the ‘Intangible ROI’ parameter in terms of the delta between the (ABC-M) scores for each stakeholder before and after the innovation attempt. So that we end up with something like:

Where K is a constant that can be used to ensure the weight of the intangible ROI result is equitable with the (much more easy to measure) tangible ROI. Simple when you know how. Or, if not, keep your eyes peeled on the coming ezine issues, where we’re expecting to publish a case study or two. And maybe reveal a ‘was that really an innovation?’ surprise or three.