“You could take Michael McIntyre home to meet your granny. You couldn’t take Frankie Boyle home to meet your granny… McIntyre articulated things you hadn’t realised you thought. Boyle articulated things you thought but didn’t feel you ought to articulate.”

If you follow me on Twitter, you might have noticed a flurry of 2×2 matrices recently. They’re becoming a bit of an addiction. Mainly, I think, because they’re as good a way as we’ve yet found to talk about contradictions, and their importance in the innovation story.

I’ve also been reading a lot about comedy in recent weeks. It was a merely a matter of time before the two threads crossed. The link came from reading Stewart Lee’s very excellent book, ‘If You Prefer A Milder Comedian, Please Ask For One’. If you ever want to get a real insight into the mind of someone at the very top of their stand-up game, as far as I can see, this is the place to start. It’s where the quote at the head of this short article came from. Any time I read about this kind of either/or spectrum these days, I’ve learned to recognise that a contradiction, and therefore a 2×2 matrix, isn’t too far away.

First up though, a health warning is perhaps in order. One of the best ways to take the joy out of comedy is to try and deconstruct it. To a large extent the same problem exists in the world of innovation. It’s something the SI research team is acutely conscious of. Many ‘innovators’ and the vast majority of ‘creatives’ I’ve noticed, actively don’t want to ‘destroy the mystery’ of their craft. The more sensible ones – the ones that get the idea that once we unravel one mystery there’s always going to be the ‘next one’ – have a different problem. And that’s the problem of never being able to step in the same river twice. Every complex case is different from every other one, so how can you ever be sure that when we’re reverse engineering previous case studies we’re not finding patterns that don’t actually exist. One of the answers is that you need to be looking at the world through a ‘first principles’ lens. And part of that means, in at least part, looking for contradictions.

That said, it is – as Stewart Lee manages to prove both in his book and on stage – not necessary to destroy the humour by deconstructing the humour. If you get it really – first principles – right, you can get the best of both worlds: analysis of funny stuff that is funnier than the original funny stuff.

I’m not sure I’m good enough to achieve that kind of feat, but I think that, by decoding Lee’s comedy spectrum I can help see why he’s so much better than other stand-ups (apart, maybe, from his wife Bridget Christie who blew me away when I saw her at a gig last month), and as a result, help innovators to see the sort of – first principles again – things they might usefully translate across from the comedy to the innovation world.

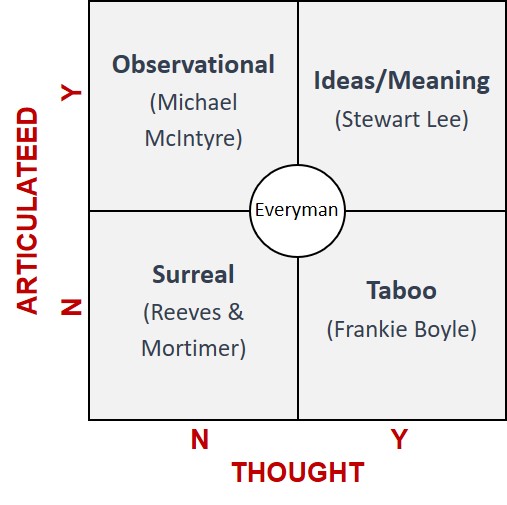

So, to the 2×2 matrix. On one end of Lee’s spectrum is the observational comedy of people like Michael McIntyre. Observational comedians ‘articulate things you hadn’t realised you thought’ (“there’s no love in homes any more because everyone’s fighting for the one phone charger in the kitchen”). The other end is Frankie Boyle-type taboo comedy (try https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TDBjoSSzI1Y for Boyle’s ‘Top Ten’) – articulating things we were all thinking but daredn’t say. The two ends give us the top-left and bottom-right corners of a matrix with ‘articulated’ and ‘thought’ as the vertical and horizontal dimensions:

Placing the spectrum onto a 2×2 forces a recognition that there are two other boxes to think about. The bottom-left box in this case is the situation where comedians talk about things that people at large have neither thought about before, nor tried to articulate. For me this is the surreal comedy of people plike Reeves & Mortimer (“eranu/uvavu”). The bottom-left corner is rarely a good place to be in 2×2 matrix convention. Reeves and Mortimer have sustained a fairly long career, but very few other surreal comedians have.

Top-right is the place to be if you can. Getting into this box is difficult because it means solving the thought-articulated contradiction. This is the ‘third way’ solution that delivers the best of both worlds. For me, Stewart Lee and Bridget Christie are the two best (only?) exponents of comedians that achieve this feat of magic. They talk about things that we all think about and all talk about, but do it in such a manner that we are exposed to ideas that reveal a higher level meaning.

The top-right box of this comedy matrix is, I believe, the only, part of the 2×2 where new meaning is created. The other three boxes all deliver output that is at best meaningless, or at worst a destroyer of meaning.

A few months ago I wrote an article for the SI ezine all about meaningful and meaningless innovation. 98% of all innovation attempts fail. That’s pretty bad. But what we thought was worse was that 70% of the 2% of ‘successful’ attempts had done so by negatively impacted meaning.

The 2% number tells us that no innovation is easy. The 70% tells us that, if you want to make it as easy as possible, do meaningless stuff. Which predominantly means observing (Michael McIntyre-like) what people didn’t know about themselves and give them a faster, simpler, more convenient, solution that, the moment they think about it they realise its just what they always wanted. Or, if that doesn’t work, do something tasteless or something surreal like a pet-rock.

Personally, though, I think I’m happier working with teams that want to be in the top-right box. Looking at the world we can all already see and already articulate, challenge the contradictions and create a more meaningful, 1+1>2 solutions. You need to watch out for the hecklers though, they can be mean.