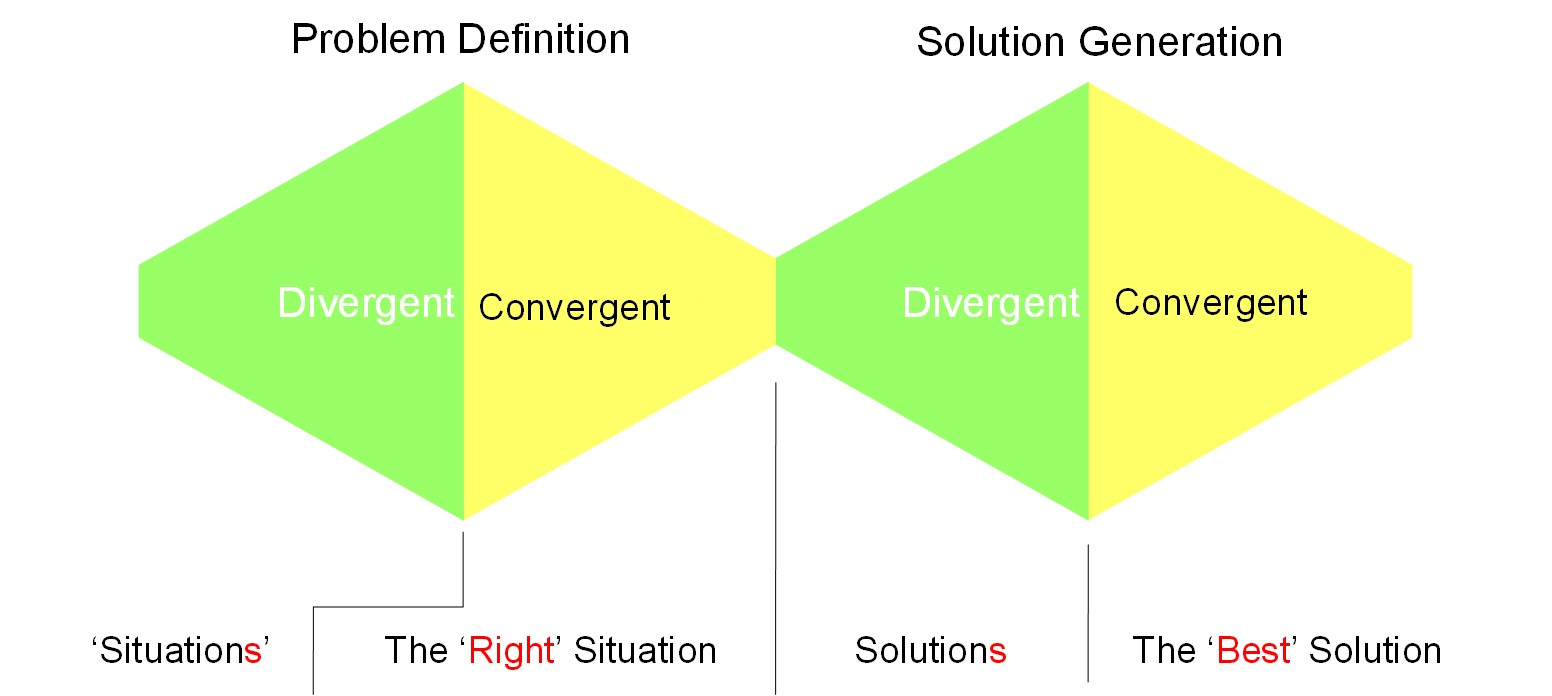

There isn’t much that the ‘creativity community’ agrees upon, but one thing that seems as near universal is it’s possible to get is the importance of divergence and convergence in the creative problem solving process. Divergence being the parts of the process where we open ourselves up to a greater number of possibilities and options; convergence being the parts where we home in on ‘the’ problem or ‘the’ answer. In our version of the divergence/convergence story there are a minimum of two divergence-convergence pairs in any problem involving a complex problem. There may be more, of course, as a project iterates its way out of the fog towards clarity, but, if a team gets really lucky, they might get away with a divergence-convergence pair to define what the right problem is, and then another pair to get to the best answer:

Irrespective of the actual number of divergence-convergence cycles might occur in a given project, one of the things that is often overlooked is the relative amount of time spent in each of the divergent and convergent phases of the cycle.

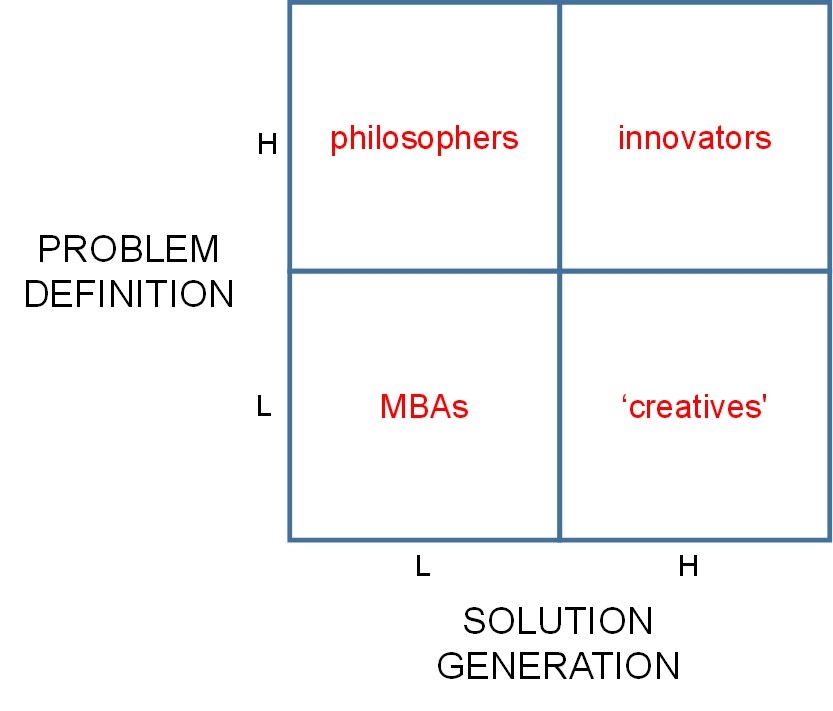

Based on our experience facilitating sessions over the years, it is a really good idea to have a prior indication of the preferred working practices of the team you’re working with. We’ve identified four main kinds:

The most frequent kind of group is the type we might think of as the MBAs. These are the people that have been taught at one business school or another, that complex problem solving requires the same laser-like focus as any other kind of problem. Anything that feels like it’s deviating too far away from ‘the point’ of the exercise (i.e. is ‘diverging’) isn’t going to be looked upon with much positivity from this kind of group. And woe betide the facilitator if a clear answer hasn’t been delivered at the end of the session. From an innovation perspective, as well as being the most frequently encountered type of group it is also the one least likely to deliver any kind of useful output once the cold light of tomorrow arrives. Solving complex problems is not at all like the ‘usual’ MBA problem. Actually, neither is real life. Which is a whole other problem, albeit one that is beyond the scope of this rant.

The rarest type of group – unless you’re fortunate enough to work in the aerospace or other industry that innovates at glacial speeds – are the philosophers. These groups are the ones that totally get what Einstein was getting at when he said, ‘if I had an hour to save the world, I would spend 55 minutes defining the problem’. This is the group that will be very happy to spend a whole day drawing intricate function analysis diagrams, wall-size perception maps or any other kind of problem definition tool you might care to pass their way. They might well have a point. But they’re also very prone to ending the ideation parts of a project with a single ‘answer’. This is the type of group that, during the rare moments when solution generation can be contemplated, usually has the greatest amount of difficulty with instructions like, ‘I don’t care about the quality of the ideas at this point, let quantity come first’. The facilitator of this group might accrue – if he’s really lucky – half a dozen Post-It’s come the end of the session, and chances are all six will contain some well-thought through ‘competent’ answers. Sadly, however, they are very unlikely to have anything at all in common with ‘wow’ or ‘breakthrough’. What the philosophers find hard to grasp is the idea that wow comes from combinations of partial ideas and that you only get to make the combinations if somebody wrote down the dumb partial ideas in the first place.

The second most frequent type of group is the opposite of the philosophers. This is the group that will typically wish to spend no more than twenty minutes working out what the problem is, and then the rest of the day re-decorating the walls of the room with Post-It’s full of solution ideas. I tend to think of these types of groups as the ‘creatives’. Mainly because it tends to be the style adopted when a group is being facilitated by a ‘creativity consultant’. By all accounts a group of people that has fallen under the collective delusion that the reason most innovation attempts fail is that ‘people don’t know how to be creative’.

Looking back through the last two decades I think I’ve only ever experienced two groups that really didn’t know how to be creative. One was a session I ran with the UK Treasury, where approximately 5% of the delegates had heard of brainstorming. The other was a session with a group of Belgian automotive engineers. The look of panic in their eyes when we announced we were looking to spend the next hour using the TRIZ Inventive Principles to generate a target of 50 solution clues was a joy to behold. Their scared-out-of-their-wits cry of ‘but what would we do with all those ideas?’ can still bring a smile to my mouth fifteen years after the session.

Anyway, Treasury officials and Belgian automotive engineers aside, the problem of having ‘too many ideas’ is one I never experience. Which probably goes a long way to explain why I spend so much of my time avoiding and distancing myself from the ‘creativity consultant’ world. Never, to paraphrase Winston Churchill, have so many been so deluded for so long. To all intents and purposes their belief that ‘people don’t know how to be creative’ is one of the most damaging collective delusions of the last 80 years since Alec Osborn wrote ‘brainstorming’ on his forerunner version of a Post-It.

I have a sneaking suspicion this ‘creatives’ segment of the 2×2 matrix is the most dangerous one of all in terms of failing to deliver anything remotely resembling innovation (i.e. ‘successful step-change’). Probably in no small part because, having brought in a – the more expensive the better – creativity session facilitator and filled several walls with great solutions, management are lulled into a false sense of security. Or, failing that, at least a warm, fuzzy plausible-deniability answer for their bosses when everything goes pear-shaped six months further down the line, ‘we brought in the best consultants on the planet, what more could we have done?’ Well, how about, ‘spend more time making sure you’re working on the right thing’?

Which, finally, leaves the top-right hand box of the matrix, the ‘innovators’. As per usual 2×2 matrix convention, the top-right hand corner is the place everyone is supposed to aspire to. The box that means we get the balance right between divergence in the problem definition and divergence in the solution generation tasks. Or rather – again per convention – solve the contradiction between them. This is the box we’re always trying to get clients to operate in. If we say that 2% of all innovation attempts work out, you can place a safe bet that 1.999 of that 2% were groups that operated in this box. If more people knew that, maybe we might all stand a better chance of living in a world that was able to meaningfully tackle what lies ahead, as opposed to our continuing propensity to kick ever more dented tin-cans along rutted roads.