“Incontinent the void. The zenith. Evening again. When not night it will be evening. Death again of deathless day. On one hand embers. On the other ashes. Day without end won and lost. Unseen.” Samuel Beckett

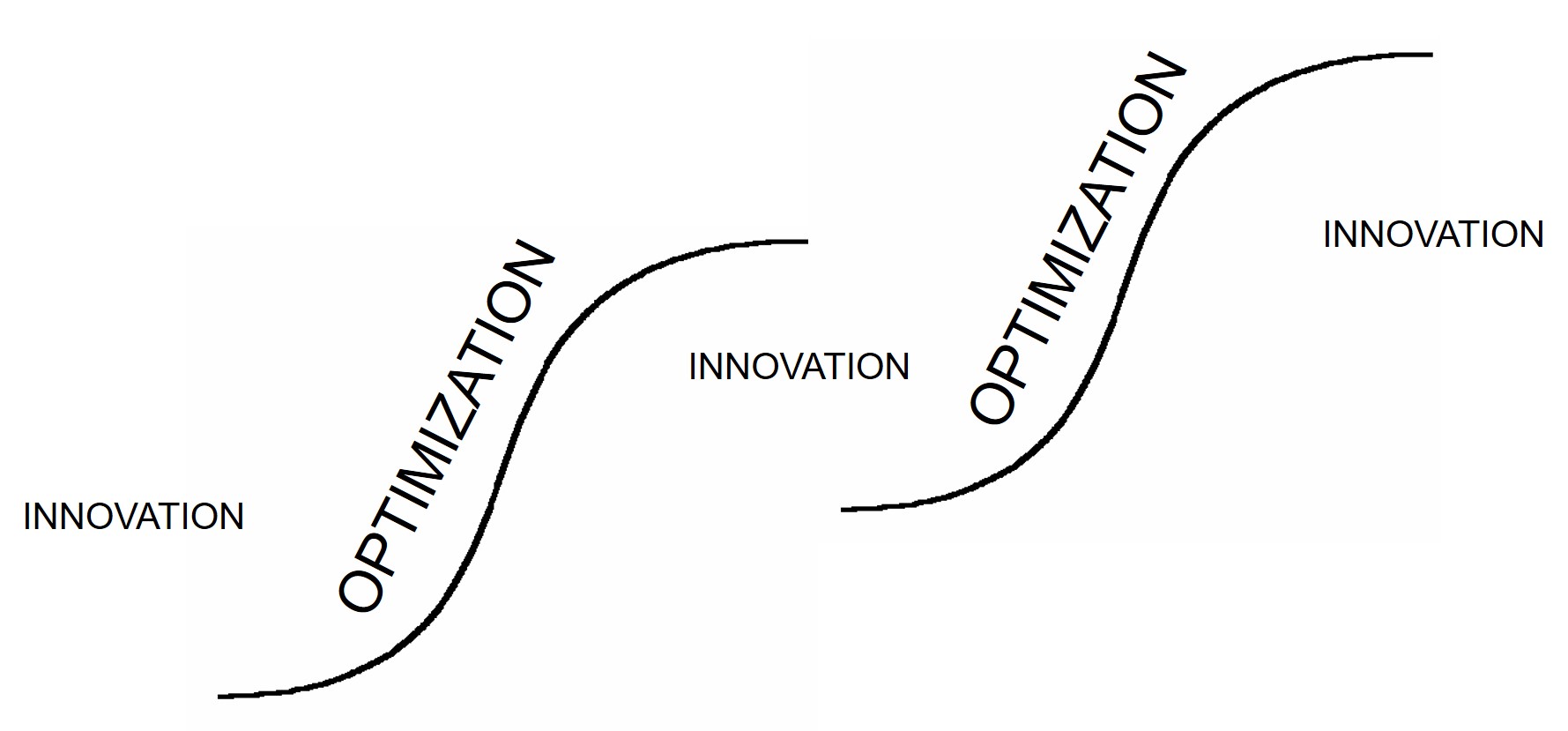

We use the expression ‘successful step-change’ to define innovation because it takes us right to the heart of the world of s-curves. The ‘step-change’ in question being the jump from one curve to the next. We usually draw the s-curve-jump story to look something like this:

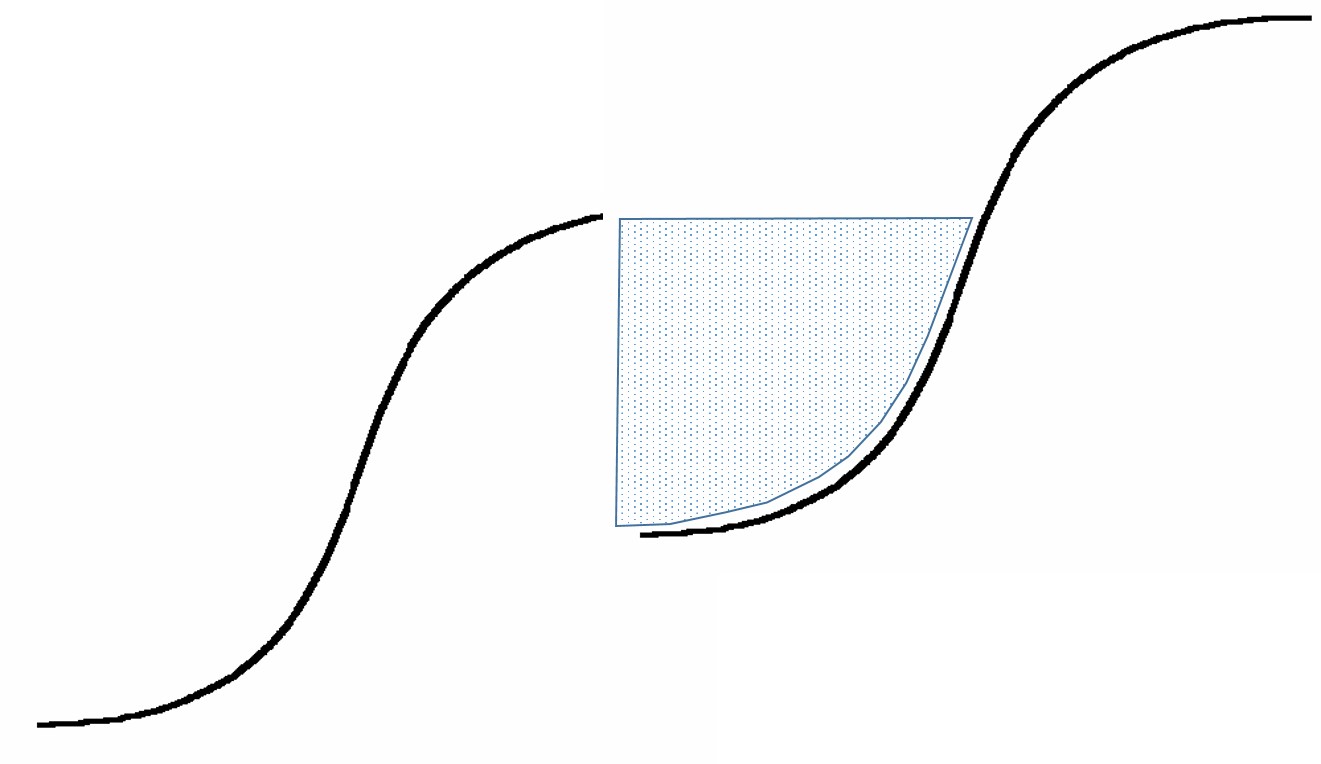

There are no hard and fast rules about the relative positioning of two adjacent s-curves, but we know for sure that a big part of the innovation management job is successfully managing the gap between the two. And specifically the void defined by this area:

Whenever an enterprise embarks on an innovation project, they essentially make a decision to jump off the top of their current curve into the unknown of the coming ‘next world’. However we choose to measure the vertical axis defining the s-curve, this jump almost inevitably results in things looking and feeling worse than we felt when we were safely ensconced on the top of our current cliff. The trick to our descent and then – hopefully – rise up the next s-curve is to reach the point where the height we’ve ascended to on the new curve reaches the level we’re at on the top of our current curve. This is what the shaded area is all about.

Managing the Void, then, is all about minimising the area of this shaded region: the smaller the area, the faster everyone accepts that the innovation attempt being made has been successful. Or, put another way, the smaller the void area, the less time and money we have to invest in getting the project out of the red and into the black.

Given the fact that 98% of innovation attempts still end in failure, it is probably fair to say that the majority of enterprises on the planet are uncomfortable when it comes to managing the void. Most enterprises still see the world through Operational Excellence eyes. Which means they focus on improving what they have, rather than jumping off a cliff into some mysterious, unknown ‘void’.

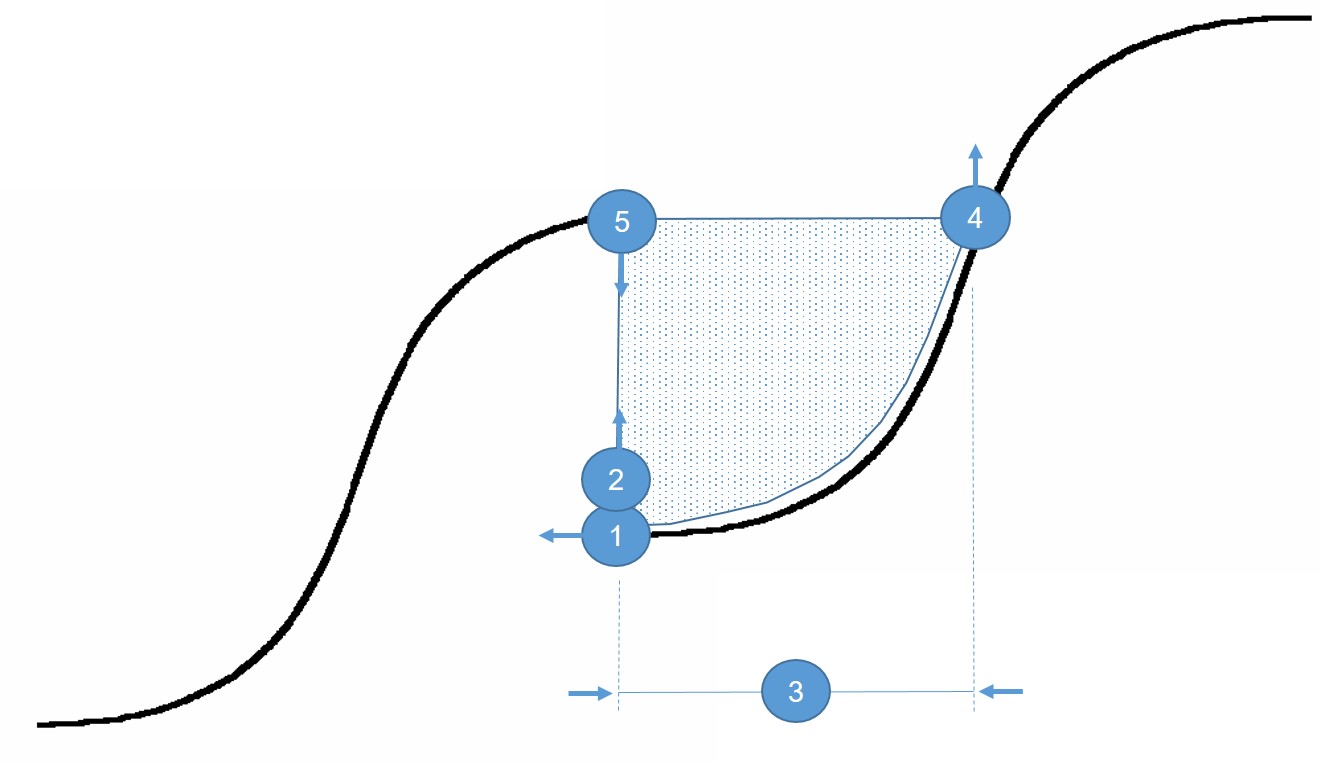

As far as we can see, when we look at the 2% of innovation attempts that end in success, there are five basic strategies for managing the Void. None is mutually exclusive, and if we really were ‘managing’ our s-curve jump we would no doubt look to adopt as many of the five strategies as makes sense given our available resources. Here are the five in graphical terms:

And here’s what each of the five means in practical terms:

1) ‘Start Earlier’ – in many ways the easiest of the five strategies to engineer and manage, but, alas, in most enterprises, the strategy that gets adopted the least often. One of the best ways to manage the step-change from one s-curve to the next is to start work before we reach the top of the current s-curve. Starting to look for the new curve when we’re on the steepest climbing part of the current curve makes the most sense since that’s when our margins and cash-flows are at their strongest. The problem, however, is that most organisation leadership teams think that the best way to manage their affairs during the exhilarating climb is to put all of their attention on the job of maximising margins and revenues. Nobody, it seems, wants to be seen to be the killjoy that tells everyone that the future won’t always be so rosy, and we should start planning now for future rainy days.

2) ‘De-Traumatise’ – when people are stood on the top of their current s-curve, it means they’ve done an awful lot of hard work to get there. Their system has been massively optimised, everything has been worked out, and everyone has settled in to their comfort zone. No matter how good the new solution that kicks-off the start of the next s-curve is in reality, it looks and feels worse to everyone who looks at it from the perspective of the beautiful position of the existing system. Managing the Void strategy 2) is thus all about managing the psychology of change and the innovation version of the Kubler-Ross Grief Cycle – first we experience the shock of the new, then we deny it, then we get angry, then we try and bargain our way out of the difficult situation, then we get depressed, then we accept a little realism by testing the new, until, finally, we accept the change, and realise, it’s not as far down as it looks. ‘De-traumatising’ is about letting people still safely positioned on the old s-curve see that getting worse to get better is sometimes just how the world works.

3) ‘Climb Faster’ – the strategy that sits at the heart of ‘Lean-Startup’ and Design-Thinking – methods and processes that are all about making lots of rapid iterations of the new solution, exposing them to customers, learning from their reactions, and building new iterations as swiftly (and as cheaply) as possible. ‘Fail-Fast, Fail-Forward’ is the frequently heard mantra of teams comfortable operating in the Void: we can’t know everything right now, so our job is to try new things, learn from it and use the learnings to design the next iteration of the solution.

4) ‘New Measures’- perhaps the least immediately visible of the five possible strategies, the ‘new measures’ strategy is about recognising that in a large majority of cases, when innovation happens, it comes alongside new ways of measuring ‘success’. When JCB first invented the hydraulic earth-mover, for example, it was significantly inferior to the industry-standard cable-driven earth-movers in terms of earth-moving capacity, but what JCB understood before anyone else was that ‘value’ to a customer wasn’t just about how much earth could be lifted in a single bucket-load, it was also about how easy it was to get the earth-mover on-site, how manoeuvrable it was once it arrived, and how flexible it was. It was ultimately about earth-moving productivity, and if you spent a week less time getting the earth-mover on site, that more than compensated for the inferior bucket load. None of which were measured by the cable-driven earth-mover companies. When JCB showed earth-moving contractors how to re-frame and re-define their success criteria, that was when their business really took off.

5) ‘Unlearn’ – In some ways analogous to strategy, 2), but the focus in the ‘unlearning’ strategy is to get people to recognise that being on top of our current cliff is not as good as we think it is. It means key parts of the learning to get to the top of the current curve has become ‘waste’ and therefore needs to be thrown away. No-one likes to think of devoting lots of hard work to create what looks like irrelevant outputs. Until such times as everyone understands that this kind of ‘un-learning’ is an inherent part of the step-change process, s-curve jumps are always going to appear difficult. Managing the Void strategy 5) is therefore largely about educating people to understand this is how the world works – fundamental means fundamental – and that we periodically unlearn stuff in order to protect the future stability of the enterprise.