“It was vertigo. A heady, insuperable longing to fall. We might also call vertigo the intoxication of the weak. Aware of his weakness, a man decides to give in rather than stand up to it. He is drunk with weakness, wishes to grow even weaker, wishes to fall down in the middle of the main square in front of everybody, wishes to be down, lower than down.”

Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being

One of my longstanding theories, no doubt borne of the last twenty-some years of working with TRIZ, is that there aren’t that many problems in the world. In my mind I’ve imagined the total number is somewhere in the vicinity of a hundred. The more I think about it, the lower the number gets.

We’ve been doing lots of projects in the healthcare sector in recent months, trying to understand how to solve the crippling rock-and-a-hard-place contradictions in a system that everyone seems unable to change. We’ve also been doing some work with employment agencies, trying to get long-term unemployed people back into work. And then with transport sector bodies trying to reduce the number of complaints they receive from an ever growing, ever more demanding population of commuters.

Each of them thinks their problem is unique, but each time, when we’ve constructed a map to show how all the different opinions, policies and vested interests interact, we keep coming up with the same basic finding: as individuals we – all of us – increasingly find ourselves sliding down a slippery slope towards helplessness, and reliance on others – usually expensive officialdom – to sort out our problems for us.

How could that be? How can we find ourselves in a society in which literally millions of people find themselves on this slope. Do none of us have the gumption to say, ‘enough already’, or, per the words of pub landlord philosopher and comedian, Al Murray, ‘snap out of it’?

It felt like time to draw another map.

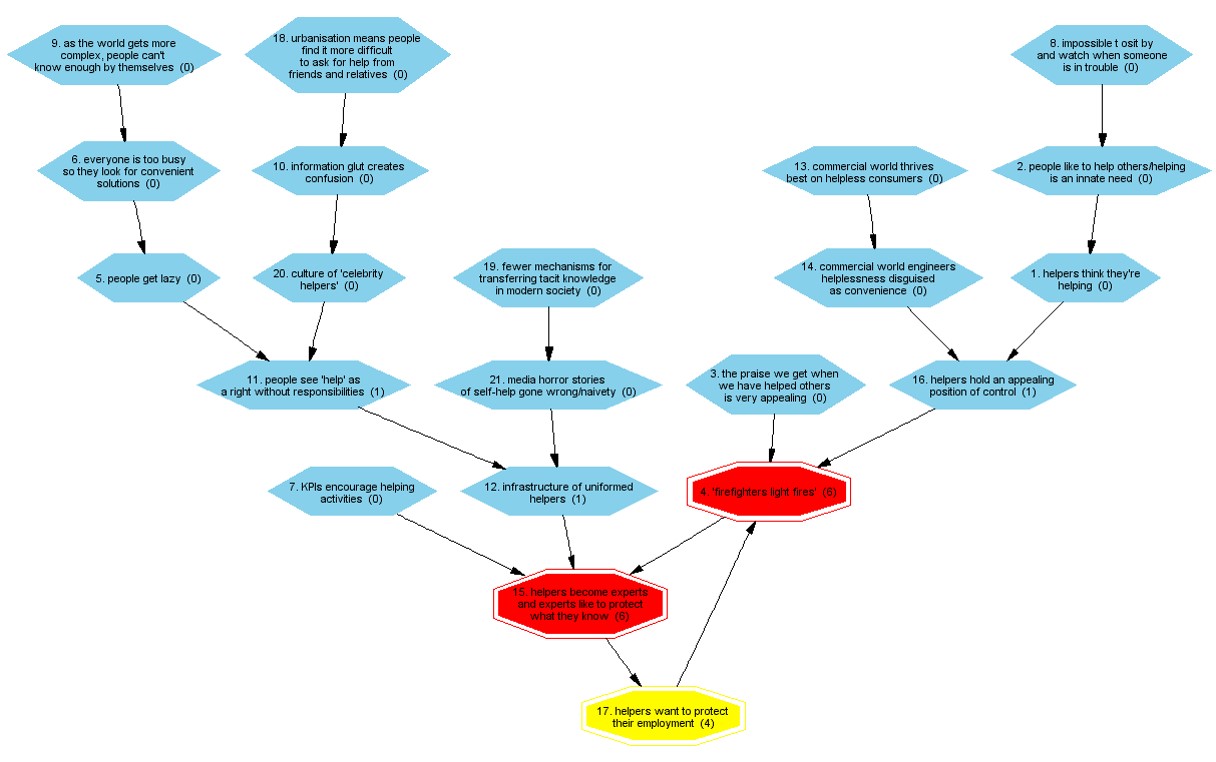

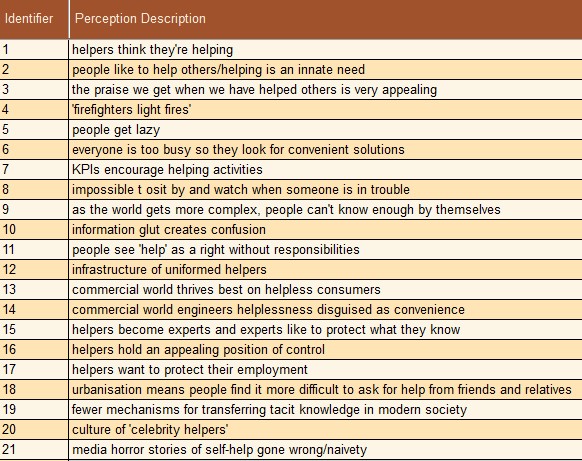

As usual, the start point was to define a question. In this case it was: ‘a culture of learned helplessness has arisen because…’

Then we set about scouring all the reasons we could find, across all the different sectors of society where we could see evidence of the slippery slope. We ended up with a list of just over twenty different answers:

Then we looked at the interactions between these answers by asking the ‘leads to’ question, ‘which of the other ones does this one lead to first?’

Then we looked at the interactions between these answers by asking the ‘leads to’ question, ‘which of the other ones does this one lead to first?’

Here’s the map we ended up with:

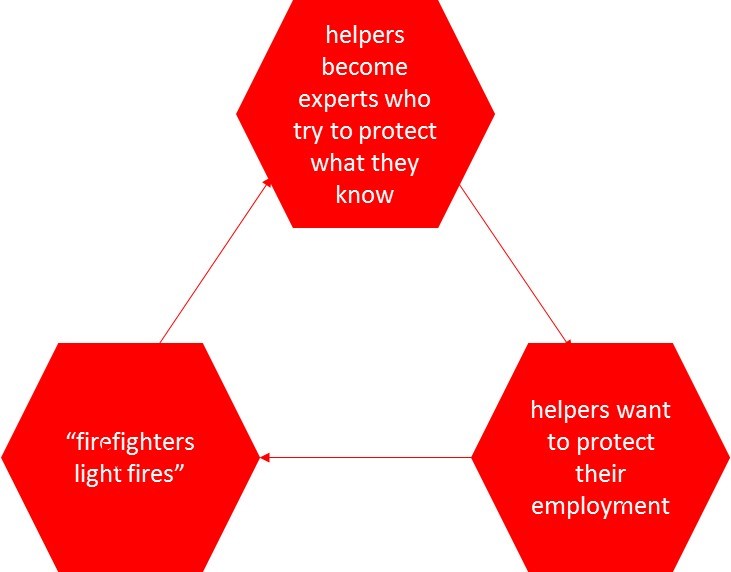

It clearly showed a single vicious circle. If there’s a slippery slope at play in the learned helplessness problem, chances are this is where it is. Which turns out to provide something of a shock. At least to my way of thinking. Here’s what the vicious circle looks like close up:

What it basically says is that the principle driving force behind learned helplessness is… the helpers.

W Edwards Deming famously said that nearly all (he eventually ended up at 95%) problems come from the system rather than the individuals within it. No-one comes to work to do a bad job. It’s just that somehow, all that positive intent sometimes finds itself combining in ways that create unfortunate outcomes no-one could have expected. In other words, while the vicious cycle tells me that the helpers are the problem, the real problem is the emergent complexity of their combined actions.

Blame is not the point. The point – for all of us helpless ones – is that when we’re trying to change our behviours and finding it really difficult, the very people we go to for help, aren’t helping. In the words of Nicholas Taleb, society has inadvertently made us all much more fragile. We live increasingly on a fragile knife edge, and the only way to turn things around, to make ourselves ‘antifragile’ is to realise who the enemy is. The enemy is us. Us plural.