Aerospace engineers tend to be glass-half-empty kind of people. The same pretty much applies to ex-aerospace engineers like me. Pessimism kind of goes with the job. It’s the way you get to build the world’s safest industry: don’t believe anything anyone tells you; look for evidence; don’t stop until you’ve got enough of it, and seen enough of it with your own eyes to ensure the aeroplane you’re designing won’t fall out of the sky.

Living with this kind of perspective can be a heavy burden. One, it puts you somewhere close to the bottom most people’s list of other people you’d love to have at your next party. Two, in these post-truth times, the ratio of truth-to-crap can very easily become overwhelming. Particularly if you spend any time on social media. Which I increasingly try not to.

Up until recently, however, I did have a certain fondness for a good documentary. Now, alas, even that pleasure has gone. It went sometime during a programme on vaccinations that I caught up on last week. The programme centred around the tragic story of the return of previously eradicated diseases like measles. Measles is back because fewer and fewer parents are getting their kids vaccinated. In theory, it was a slam-dunk kind of story: a few decades ago, a couple of clinicians with poor knowledge of how to design an experiment and a large egomniac-clinician-sized chip on their shoulder published ‘research’ showing that vaccines are dangerous. They’re listened to for a while. Then they are discredited. End of story.

Except, in their desire for ‘balance’ the documentary makers – who also, evidently had no understanding of experiment design either – brought together a collection of interviewees, who for the most part also didn’t understand experiment design, and collectively then stitched together a narrative that failed to make the nonsense clear. I’m guessing, largely because there is no simple way to tell the story. And, above all else, it seems, the public wants and expects to here simple stories.

While I don’t doubt the nonsense of the discredited clinicians, the disappearance of my faith in documentary makers during the programme arrived with the thought that the documentary makers had absolutely no desire whatsoever to uncover and reveal the truth. Rather they were intent on making hour-long clickbait.

And, what they’ve learned from social media is that the best way to do that is to create content that evokes strong emotions. Preferably negative ones. People are, to my reckoning, around seven times more likely to respond to anger-inducing nonsense than they are fluffy-kitten, isn’t-it-loverly kind of nonsense.

Beating a 7:1 tide of crap is hard work. In the words of the aphorism, A lie can travel halfway around the world before the truth can get its boots on. Except, thanks to social media and the amazing self-learning algorithms present on Facebook, Twitter and the like, the lie has now done seven laps of the equator before the truth has even thought about boots.

All that said, as well as being a natural pessimist, I’m also a great optimist when it comes to believing that any problem is solvable. That’s what TRIZ did for me.

The post-truth problem is eminently solvable.

In theory.

In practice, when I combine my glass-half-full and glass-half-empty perspectives, its very easy to turn a solvable problem into an unsolvable one by introducing one too many constraints.

In theory, the post-truth problem can be solved, in the short term at least, by:

1) Acknowledging that human evolution has not yet reached sufficient maturity to deal with social media, we switch the whole shebang off.

2) Locking Mark Zuckerberg up in solitary confinement with a collection of Dunbar Number research and not letting him out until he understands there is no such thing as ‘connecting everyone’. Meanwhile all of his ill-gotten gains are re-distributed to each of the countries who’s elections, referenda and government surveys have been corrupted by his democracy-breaking algorithms. To pay for the re-running of those elections, referenda and surveys in a legal fashion.

3) Getting the mainstream media to re-recognise the idea that ‘balance’ is not about giving an equal voice to the different sides of an argument when one side is plainly and provably lying (“If someone says it’s raining, and another person says it’s dry, it’s not your job to quote them both. Your job is to look out the fucking window and find out which is true.”). To help journalists determine truth, we use software to assist in the identification of liars, deluded people and troublemakers.

4) We revoke the media ability to do voxpop interviews. Interviewing idiots in Stoke, while admittedly sometimes funny, is in reality nothing more than clickbait. Dangerous clickbait.

Of course, in practice, none of this will happen. Except in China. Which is a whole other story. One that currently rests on the general mis-understanding that politics is a two-dimensional left-right spectrum rather than a contradiction needing to be solved.

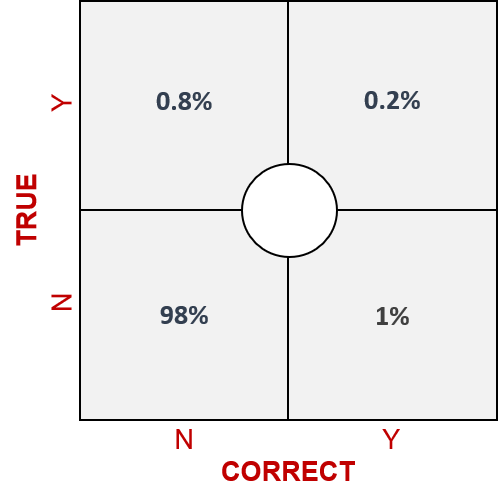

Meanwhile, on a personal level, while I’m often tempted to adopt the increasingly widespread strategy of blocking idiots from Stoke (other cities are available), I also know that this strategy also doesn’t work. Two-dimensional thinking again. Thinking that serves merely to increase the separation between the myriad us-bubbles and them-bubbles. What I need to do instead is to at least manage the contradiction. Which, as of now means remembering the importance of a two-second pause between reading clickbait and responding to it in order to realise there’s no point responding to it. Then all I need to do is keep in mind that 98% of what I’m exposed to these days is clickbait.

Which means lots more pauses than I’m used to. Who knows, if I’m somehow able to pool together some of those pauses I might re-gain a more sedate, relaxed, time-to-think lifestyle. And an end to blood-pressure medication.