‘That’s cheating’ is a frequent reaction when any of us hear an inventive solution to a problem for the first time. Cheating in the context of inventive problem solving is all about breaking rules. Sometimes breaking rules is a good thing. And sometimes it isn’t.

The recent VW emissions testing debacle is a good illustration of breaking the rules in a bad way. We still don’t really know what’s happened for sure, but the fact that the company has admitted that cheating took place probably tells us enough to speculate on the reality: cars are subject to increasingly strict emissions legislation and VW found themselves in a position whereby they were unable to meet those targets. Faced with the prospect of not being able to sell their cars, the engineers must have somehow found themselves in a horrible ‘rock and hard place’ conflict. Sadly, it appears they took a ‘bad cheat’ approach to their conflict. Better, someone in the company decided, to cheat the tests than to potentially put the company out of business because they didn’t have a legislation-compliant product.

I had a similar legislation-compliance cheating situation myself in the 1990s. We’d invented a low water consumption toilet and were busy trying to license it to one of the UK manufacturers. A big part of our rationale was that the legislation was changing and the toilets being produced by the industry would no longer be compliant. I quickly became frustrated by the lack of interest in our invention. Not only did it exceed the new water consumption regulations, but it was cheaper to manufacture, more compact and more hygienic. None of the manufacturers seemed to care. Finally, I got one of them to explain why they weren’t interested in the new design, despite the fact that their current designs were about to become illegal. “You don’t understand how this industry works,” said the chief engineer, “we can’t afford to innovate. Far easier for us to write to the Government and tell them that if they insist in enforcing the new legislation, they will kill the industry and risk losing thousands of jobs.”

To my mind, although this wasn’t an illegal response like VW’s, it was still an unpleasant case of ‘bad-cheating’ in action. Especially when looked at from the societal and environmental perspective with literally billions of gallons of wasted water at stake: we were all cheated by an industry that thought it was easier to write a letter than think about the problem.

I guess a part of my frustration arose from my previous experience in the aerospace industry. Just as in other sectors, the aerospace industry is heavily regulated. The pressures on manufacturers to improve energy efficiency and reduce emissions have been just as high as in the automotive sector. But the response of the industry to these ever more stringent requirements has been somewhat different.

In the case of VW and the UK water industry, the reaction to a requirement that was beyond the realms of current capability was to break the legislator’s rules. In the aerospace industry, on the other hand, there is a clear understanding that the regulations exist to advance our understanding of how the world works.

When the aerospace regulators specified parallel reductions in NOx and SOx emissions, for example, they knew, as did engineers in the industry, that the two requirements were in many ways contradictory. Increasing combustion temperature improved one but made the other worse. And vice versa. ‘The Science’ said we could have low NOx or low Sox, but not both. In TRIZ terms, we can see the challenge to be a classic contradiction: we want combustion temperature to be ‘high and low’. And that’s the convention the industry set about challenging, fairly rapidly turning the paradox into a suite of combustion system designs that achieved the ‘impossible’: designs that had both high and low combustion temperature, and both low NOx and low SOx. The designers here too had to break the rules. But the rules they broke were the ‘laws’ of physics and chemistry. Or rather mankind’s rather limited understanding of those ‘laws’ and the hidden incorrect or incomplete assumptions they contained.

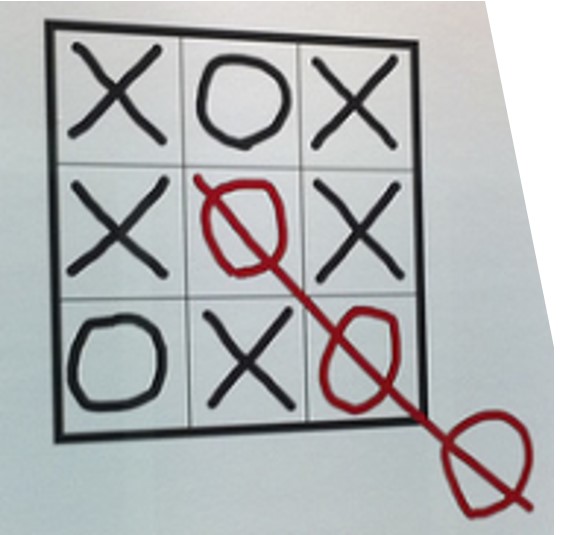

That’s good cheating: Breaking rules that we had wrongly assumed were rules. The ‘laws of physics’ that turn out to be nothing of the sort. The trade-offs that we’d assumed were inherent, but turned out to be merely the next contradiction to be solved.