Given the enormous acceleration in the corruption of the word ‘innovation’ in recent months (the stupid and dangerous ‘Investors in Innovation’ scheme from the UK Government being something of a last straw), the Systematic Innovation team have been spending a lot more time thinking about the reactive version of innovation, ‘organisation resilience’. It’s often difficult to get a senior leadership team to engage in actual innovation activities. Sure, they will nod sagely and say that they want an ‘innovation culture’, but the bottom line is the vast majority only want it if it doesn’t require them having to change anything.

Talk to them about organizational resilience, on the other hand, or rather the lack of resilience in their organisations, and they’re – thus far at least – much more inclined to actually listen. And then actually do something when they learn they’re not a ship-shape and Bristol-fashion as they thought they were.

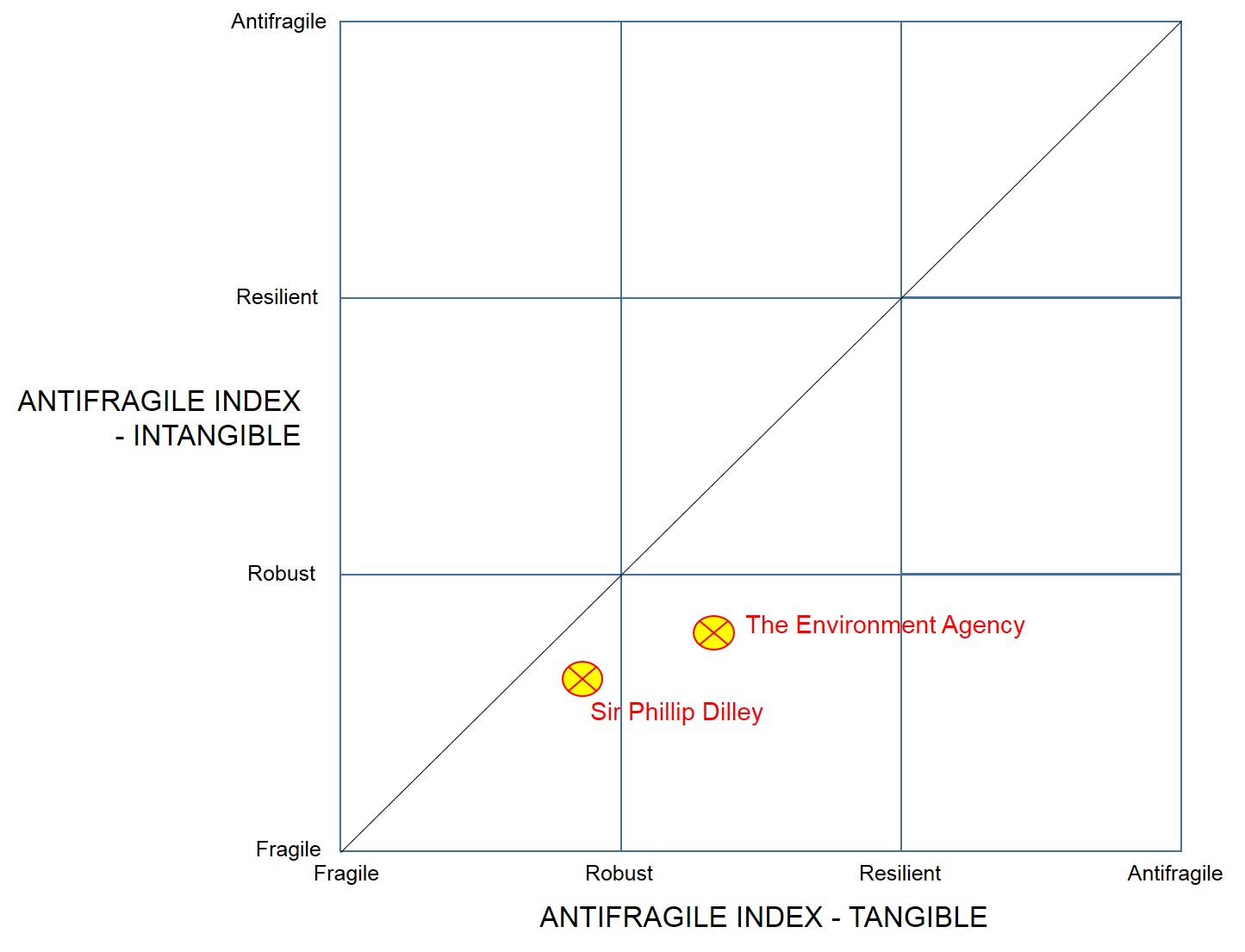

It turns out that measuring the resilience of an organisation (actually, we’re probably going to go a step further and call it an AntiFragile Index) requires a very broad lens indeed. Not only do we have to think about each of the (six) essential elements of a system for resilience, but we also have to look at what effectively becomes a hierarchy of such systems. Right at the top of that hierarchy sits the CEO of the organisation. They are the ones that in effect determine the attitudes towards the resilience of an organisation, and not just from the words they use to communicate the importance of resilience, but from the way that they themselves behave. Do what I say not what I do, much as some CEOs might think otherwise, really doesn’t hold true when it comes to organizational culture.

Take the UK Environment Agency.

One of the worst aspects of the first week of January is that I almost inevitably find myself stuck in the UK. Which in turn means I end up listening to the UK news. Aside from the swelling cocktail of global catastrophes, the prevailing news story inside the UK for the last few weeks has been flooding.

Enter head of the Environment Agency, Sir Phillip Dilley, the man responsible for coordinating things when flooding occurs.

Or rather, when we learn that Sir Phillip is on vacation in the Carribean while the floods are happening, we quickly realise his ‘entry’ into the situation is largely going to occur by phone.

Strike One. By choosing to stay in the Carribean Sir Phillip fails a very basic organizational resilience test: failure to understand the importance of basic (ABC) human emotion. I’m pretty certain Sir Phillip was sitting happily in his deckchair offering up sage advice to his troops thinking that it made absolutely no tangible difference whether he was sat in the sun, or next to a collapsing bridge in Tadcaster. In this regard, he was absolutely right, it made absolutely no tangible difference at all.

But this was never an issue of tangible reality. People make decisions for two reasons, the good one and the real one. The tangible one and the intangible one. And in forgetting – or being blindly unaware of – the second reason, Sir Phillip failed a very important test. Perception is reality. Tangibly it made no difference where he was physically located. Intangibly it made all the difference in the world. People – the flood victims for example – want to feel that ‘the authorities’ are empathizing with their situation, and when you’ve just been flooded out of your house, the last thing you want to hear is that the person responsible for putting things right is over 4000 miles away sipping tequila on a beach.

Failing to grasp the importance of intangibles is a naïve mistake in resilience terms. Sir Phillip’s second strike is somewhat more serious. Also a tad less visible in the media at the moment because the media tend not to understand resilience either.

This week, now he’s back in the UK, he was called to London to explain his actions and the actions of the Agency during the floods. And in particular why the flooding has been so bad so recently after the last round of flooding a few years ago. Here’s what he said:

“Everyone that I’ve spoken to in the affected communities said the same thing: something is different, we have never had something like this before. “That means we have to think differently.”

And then, to para-phrase, ‘if I’d been asked these questions before the floods started, everyone would’ve said we were ready’.

Now some people might look at these statements and think, aah, poor Agency, the situation was unprecedented, and therefore there was nothing they could be expected to do about it. While that might have been true (in reality, the situation wasn’t unprecedented at all), the bigger issue is the statement reveals a very non-resilient attitude to natural disaster. The statements reveal a glass-half-full attitude to the world.

When it comes to someone serving me ice-cream in my favourite ice-cream parlour, I think it’s important that the server has precisely that kind of glass-half-full positive view of life when they approach me carrying my usual order of too-much ice-cream. I’m about to enjoy myself and I really don’t want a grumpy, negative person coming along to remind me how many calories I’m about to consume.

When it comes to protecting the country from natural disasters, on the other hand, I really don’t think that a glass-half-full perspective on life is appropriate any more. Ask any aerospace engineer, and they’ll tell you the reason it’s the safest industry on the planet is because everyone takes the opposite glass-half-empty view of the world. If you want to design resilient systems, you take a very keen interest in worst-case scenarios. And then, typically, you double whatever you find, just to be sure.

There aren’t many rules in the Mann clan, but one of the very basic ones is ‘don’t live in a house that’s less than 200m higher than either the sea or nearby rivers’. It’s a rule that comes from that kind of beyond-worst-case-scenario thinking. The thought of being flooded sounds terrible, so don’t allow yourself to ever get put in that situation. It’s a rule that comes with a downside, of course. My current one being that, unless I stand on top of my chimney stack, I have no sea view. Somehow, though, it feels like a small price to pay. Especially now I’ve put a webcam on the chimney.

So No-Resilience-Strike-Two to Sir Phillip. If the CEO of the organisation is walking around thinking optimistic thoughts about how well they’re doing, they just instilled a culture of everyone else doing the same. It’s all very well to say, ‘we need to think differently’, the resilence issue is you should have known to be thinking differently twenty years ago.

‘It’ll be all right on the night’ is classic glass-half-full thinking. Except in this case it wasn’t, was it. The Environment Agency has such a glass-half-full view of the world, it seems, one might say the glass runneth over. Mostly over the Northern half of the country.

But the worst is still to come. Strike Three is perhaps even more subtle than Strike Two. But also more profound still in terms of organizational resilience or the lack thereof. It comes in two parts: the first not understanding the difference between robust and resilient; the second in not take advantage of already existing wisdom.

It has also become clear in the current flooding that the Environment Agency has taken a very robust attitude to flood defence. We know this is true because all of the language they’ve been using – and that again goes particularly for Sir Phillip – pretty much boils down to making flood defences higher. This represents a classic robust attitude to the world: make it higher, make it thicker, make it stronger. It’s a dumb way of looking at things. I can say that with confidence because – and here’s the real sin – there is very clear and widespread evidence from many previous cases around the world that it’s a dumb thing to do. Like in The Netherlands. They too adopted a very expensive, very robust, (‘Delta Works’) ‘build the dykes higher’ view of the world in the 1950s when they suffered very bad flooding from the North Sea. That worked fine until 1993, when the flood water very inconveniently decided to arrive from the non-Dutch mountains in the East instead of the sea in the West. Now those wonderfully robust dyke walls served only to keep the flood water in and 250,000 people found themselves flooded out of their homes. Robust very definitely wasn’t the same as resilient, and finally the Dutch government understood the difference. Enter the resilience-centric ‘Room For The River’ strategy. Which works on the basic assumption that when ‘unprecedented’ amounts of water arrive, the water has to go somewhere, and hence the job is to manage where that water goes. It turns out to be a very effective and proven strategy. Sir Phillip’s Strike Three sin is not instigating the adoption of a similar resilience-based approach in the UK.

Now, if I understand the rules of baseball correctly (I have no idea why I even started the baseball ‘strike’ analogy at all, thinking about it), three Strikes means you’re out.

I think if the British press had their way, Sir Phillip should’ve been kicked out of his job after Strike One. It’s still not entirely clear that that won’t happen anyway.

Personally, I think it’s very important to avoid these kinds of knee-jerk reaction. Three Strikes – especially such fundamental ones – is a lot, but the bigger question right now ought to be ‘is there a better person for the job than Sir Phillip?’ Is there anyone else in or around the Environment Agency that understands these Three Strikes of Resilience?

At this point in time, if there is, they’re keeping their head well and truly below the flood defence wall. Which, if its right there really is no-one else better qualified to do the job, means Sir Phillip should get to live another day. And in so doing get to face the Resilience ‘Strike Four’ test: does he have the humility to understand and accept that in complex situations – like weather – the most important thing is learning. Learning about how complex systems work being a pretty good start. My (PanSensic-driven) assessment of Sir Phillip Dilley is that he does not possess the requisite level of humility. I don’t see him understanding that what got him to where he is now, will not keep him there. The problem is I don’t think he understands – or has the bravery to understand – what that really means. I hope I’m wrong. PanSensic, meanwhile, rarely is.