I’m not sure whether the blind-people feeling different parts of an elephant metaphor has reached Peak Cliché yet, but it still seems appropriate when I think about some of the smart people buzzing around the periphery of the innovation world.

In their desperation to not-use TRIZ or Systematic Innovation, these smart people periodically grasp at concepts they think will explain how innovation works. We saw it vividly with biomimetics. And then uber-fad, Design-Thinking. And now I find myself hearing the word ‘exaptation’ being used as the next innovation Holy Grail. Alas, like biomimetics, it turns out to be yet another tiny part of a much bigger picture. Albeit one that is easier to understand than TRIZ… which, of course, is a big part of its attraction. To gain a meaningful appreciation of TRIZ requires time and hard work. Far easier to gather half a dozen examples of engineers designing solutions inspired by biology. Or, from the exaptation perspective, to collect half a dozen examples (most of them biological anyway as it happens) of solutions that initially performed one function that were exapted to perform another. I’ve heard the bloody bird-feather exaptation story so many times now, I come out in a rash every time I hear the latest exaptation advocate prattling on about it.

People like easy, of course. On the other hand, systematically ploughing through ten million innovation case studies is definitely hard work. Had this research showed that biomimetics or exapatation were dominant innovation mechanisms, we might well have closed the research down a decade ago. The natural world ‘innovates’ at a glacial pace. And ‘exaptation’ doesn’t happen much faster. To calibrate us on how infrequent these mechanisms are, we might note that when Genrich Altshuller started the TRIZ research and spent a decade reverse-engineering important patents to generate the 40 Inventive Principles, exaptation was not one of them. It was our work in the early noughties in fact that we tentatively started talking about ‘Change Function’ as a recognisable strategy with any kind of statistical significance. If something takes over fifty years to spot, the researchers are either suffering from massive Confirmation Bias, or the something is pretty darn rare.

So, let’s try and set the record straight in terms of which is which. Just how big a part of the innovation story is exaptation? To help with the task, let’s bring in to play the work of

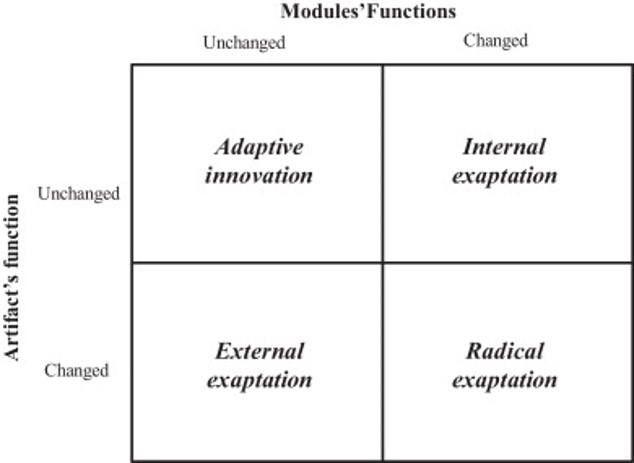

Pierpaolo Andriani and Giuseppe Carignani ( in particular, their paper, ‘Modular exaptation: A missing link in the synthesis of artificial form’), two of the current exaptation preachers. They built their thinking around a 2×2 Matrix that looked at whether an artefact did or didn’t undergo a change of function, and then whether the ‘module’ into which that artefact was contained went through its own did or didn’t change of function:

If neither artefact nor module function are changed, Andriani and Carignani use the rather disingenuous term ‘adaptive innovation’. In TRIZ terms, this type of innovation is what we call ‘contradiction solving’. Next up, what they describe as ‘internal exaptation’, is in actual fact what TRIZ calls ‘Function Transfer’. These are situations where an artefact that delivers a useful function (‘cyclone separates solid’) is installed in a domestic vacuum cleaner rather than an industrial sawmill. In so many words, this is the Dyson innovation strategy. Any connection to ‘exaptation’ here is tenuous to say the least.

More like the dictionary definition of exaptation is Andriani and Carignani’s term ‘external exaptation’. These are situation where the function of the ‘artefact’ does get changed. 3M’s Post-It Notes, Viagra, and Coal Tar offer up classic examples of this kind of Change Function innovation: Viagra was an ineffective cure for angina that turned out to be much more effective as a means of creating, ahem, male tumescence; Post-Its were the perfect solution for ‘rubbish glue’, etc.

Finally, comes ‘radical exaptation’. This is the situation where both the artefact and the ‘module’ change function. This is a much more difficult one to spot. Which means that nearly everyone ends up talking about microwave ovens, and not a lot else. Radical exaptations might indeed be important innovations when they happen, but, alas, they don’t happen very often at all.

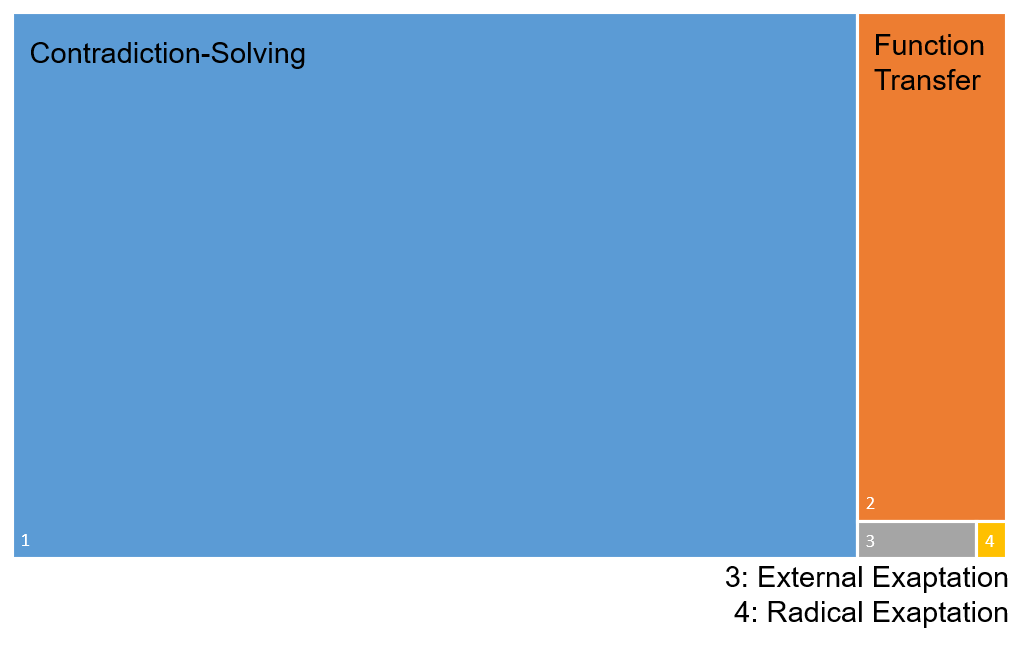

To calibrate us on just how infrequently this type of innovation happens, bearing in mind our usual definition of innovation as ‘successful step-change’ (i.e. the 2% of innovation attempts that were successful versus the 98% that failed), here’s how the four different types of innovation add up:

Which means, based on our ten million case studies, ‘exaptation’ accounts for slightly less than 1% of the story. Which, I think, is a way to say to the exaptation-advocates, ‘please shut up’. At least until you’re prepared to do the hard-yards to appreciate what innovation actually is: solving contradictions.