When I worked at Rolls-Royce, there was a joke that went something along the lines, ‘how do you remember whether it was Henry Royce or Charles Rolls who was the engineering genius? Answer: Rolls was the sales and marketing person, that’s why his name comes first’.

It was telling at the time, and I still see it most places I go. The Sales and Marketing people are the ones most likely to earn the big bucks and climb the corporate ladder the fastest. Is this because they’re inherently ‘better’? Or is it because they’ve understood how the business world works far better than the Engineers and Scientists?

If I were to exaggerate what this means, I’d say the Engineers and Scientists are allergic to corporate bullshit and much more interested in the next exciting problem to work on, whereas the Sales and Marketing people know they’re supposed to let everyone know how much they contributed to the last success before taking on their next challenge. To be slightly cynical about what I see, the Sales and Marketing people use their skills to sell and market themselves as well as – if not better than – the products and services the sell and market to customers.

Case in point. I’ve been working with a group of engineers and scientists at a big multi-national for the last few months. Never have I seen a harder-working group of individuals. Nor have I seen one so frustrated at their inability to find any time to do anything other than the urgent day-to-day ‘operational excellence’ work. I’m supposed to help them to innovate. So far I’m not winning. Operational Excellence beats innovation every hour of every day of every week in their world.

One of the engineers, bless him, told me he’d just used some of our innovation tools to help solve a customer problem. Great, I said, how much was that worth to the Company? Silence. I let the silence build. Whoever spoke next was going to have to reveal something important. The silence continued. I wasn’t going to lose this one. Finally, the engineer reluctantly squirmed and offered me an embarrassed-sounding explanation to the effect that improvements in customer satisfaction were intangible and couldn’t be quantified.

Now I had a dilemma. I’d been teaching the group about complex adaptive systems and so we all knew that there was almost no way of establishing the value of any change unless a very carefully conducted back to back experiment had been configured and conducted. And even then, in true ‘you can never step in the same river twice’ fashion, you still can’t be sure whether your intervention had a quantifiable benefit. This message seemed to have gone in. He was right: there had been no back-to-back experiment in his situation and so customer satisfaction improvements couldn’t be translated into a project value.

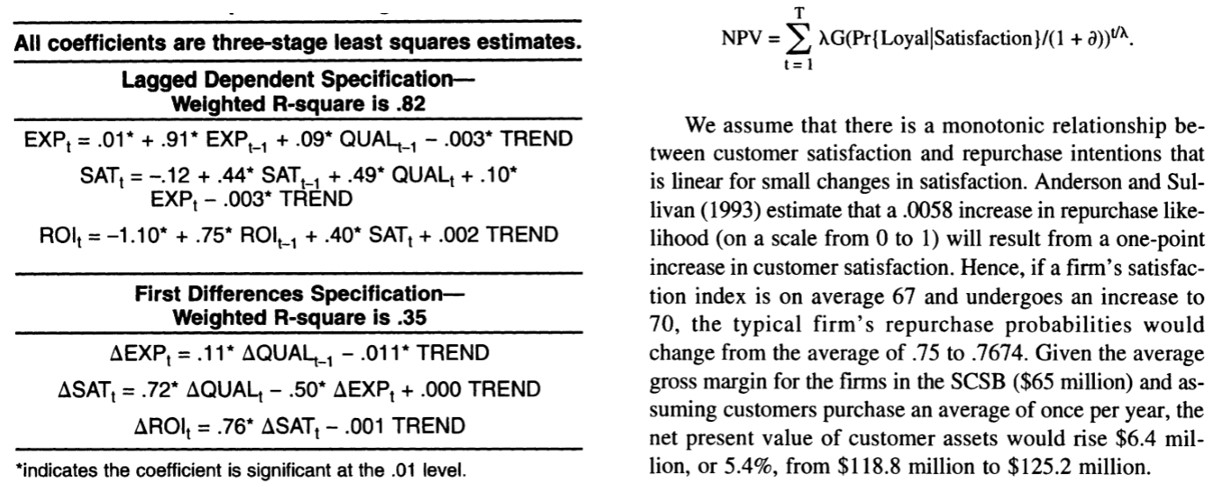

But then the other side of the dilemma was the knowledge that the Sales & Marketing people know that the real world might be complex, but the business world is all about sales and marketing. Their view of the world is that it is eminently possible to make a correlation between a percentage point increase in customer satisfaction and how much monetary value that has to the business. Sometimes they even write the method up (‘someone somewhere already solved your problem’, right?). Sometimes you find papers that publish formulas like this:

This is a classic example of what I refer to as ‘crackpot rigour’. From a complex systems perspective it is complete and utter nonsense. From a Sales & Marketing perspective, however, it is ‘evidence’. At first glance, to some, very convincing evidence. Someone did some maths. Moreover, though, it is ‘plausible deniability’. Which means that when anyone challenges you on the fictitious numbers you might create using the formula for the increase in customer satisfaction you just achieved (fictional though that probably is too, no matter what ‘scientific method’ you used to demonstrate the improvement), you simply point them to the reference. Then, assuming they even both to look, they’ll see something that looks like the maths no-one normal human understands. If they don’t understand it, they figure, neither will their boss. And then things get even better: if they use the reference when their boss challenges them on the numbers, the boss can’t admit that they don’t understand the maths. Rather, they are more likely to be impressed that the people below them are smart enough to understand this kind of gobbledy-gook. And, hey presto, everyone is bought into the numbers.

Suddenly, the ‘intangible’ increase in customer satisfaction the engineer thought couldn’t be quantified, has a very clear number attached to it: every percentage increase in customer satisfaction in our business unit is worth $350,570 in incremental future sales, and hence this project has just delivered $848,652 in tangible value to the Company. Boom.

If I’m sounding cynical here, I propose it’s exactly the same kind of cynicism that allowed people like Jack Welch to stand up and tell the world that GE ‘saved $9B using Six Sigma’. Or Sergey Brin to say in 2012 that all his Google employees would be driving autonomous vehicles within a year, and that by 2018, we’d all be able to pop down to our local car-delaership and buy one. It’s all a lie. But – and here’s the important point – if we do it right it’s a useful lie. If you don’t think you could live with your conscience making up fictitious numbers, remember what’s behind the message when people like Welch and Brin espouse this kind of quantified-fiction nonsense. They know its nonsense, but its nonsense that tells people in the organisation where they should be heading. What gets measured gets done. Connecting customer satisfaction to revenue is pure fiction, but its good fiction. In that it tells everyone in the organisation that improving customer satisfaction is a fundamentally good thing to do.