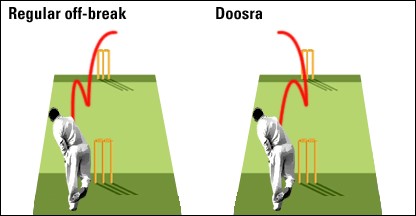

Asked to name the biggest innovations to arrive into the world of cricket in recent times (i.e. the last 30 years – this is cricket, remember) and in most people’s Top Five will be the doosra. A doosra is a particular type of delivery by an off-spin bowler. The doosra spins in the opposite direction to an off break (the off-spinner’s default delivery), and aims to confuse the batsman into playing a poor shot. Doosra means “(the) second (one)”, or “(the) other (one)” in Hindi and Urdu. The delivery was invented by Pakistani cricketer Saqlain Mushtaq. A variety of bowlers have made considerable use of the doosra in international cricket once Mushtaq started having success with the technique in the early 1990s. Users today include Sri Lankan Muttiah Muralitharan, Indian Harbhajan Singh, and South African Johan Botha.

For me it represents a lovely example of what real innovation looks like. Firstly, just looking at the dismayed expression on a batsman that’s just been dismissed by a doosra, it is successful. Second it made a step change (Inventive Principle 13 – the ball unexpectedly moves the other way). Third, it happened while remaining within the tightly controlled rules of the game. And fourth, regarding this compliance issue, like a lot of true innovations, the incumbent’s (i.e. the bowlers that don’t know how to bowl a doosra, or the batsmen that have to face them) frequent response is to try and get the bowling style banned.

Then there’s a second reason I like the doosra. It makes for a lovely simple acronym for the innovation process:

Direction

Outcomes

Obstacle

Switch/Shift/Surprise/Step-change

Resources

Action

Direction – any innovator needs a clear big-picture idea of where they’re heading. A compass that points in the direction of success. In conventional innovation terms that means ‘increasing value’. Which in turn means giving a customer more of the things they like and less of the things they don’t. In cricket terms, the big-picture direction for the team is to win the game, and, bigger still, to reach the top of the world rankings.

Outcomes – once we know the overall compass heading (‘win the game’), we need to zoom-in to look at the specifics of a situation where we think there is an innovation opportunity. If I’m a bowler running in to bowl the very clear outcome I am trying to achieve is ‘get the batsman out’. If I was being really smart, however, I’d recognise that alongside every tangible outcome need is a parallel intangible one. Tangibly my job is to get the batsman out; intangibly my job is to do it in such a way that I make my opponent fearful of facing me next time. If we think about these ‘intangible’ outcome requirements in terms of a competitive game like cricket, it’s all about making the ‘ABC’ (Autonomy – Belonging – Competence) get worse for the opponent. In an innovation environment where I’m trying to make my customer happy rather than take their wicket, my intangible outcome objective is to make ABC get better. Plus, of course, also deliver the very clear tangible outcome benefit. People need their ‘good’ (tangible) reason and their real (intangible) reason for making any kind of change.

Obstacles – once we have a clear idea where we’re trying to get to both at the high-level and in detail, the next job is to focus on ‘what’s stopping us?’ from getting there. This is perhaps the most counter-intuitive part of the innovation process for most people. We tend to veer towards trade-off and compromise. Mainly because that’s what life (and our school systems) have taught us is the optimum strategy. In innovation-world, however, we know that ‘optimum’ is merely a least-poor compromise and that our job is to avoid compromise altogether. Hence we deliberately and purposefully run towards the obstacle in order to ensure we devote our precious time and energy to the most important improvement opportunities. Typical obstacles preventing us from achieving our desired outcomes might be that ‘it costs too much’ or ‘it will take too long’ or ‘it will reduce quality’. The easiest way to find the obstacle is often to listen to the words that come immediately after the word, ‘but’ when we listen to someone commenting on our idea. As in, ‘I want to get the batsman out, but because I’m a spin bowler and therefore bowl quite slowly, the batsman has a longer amount of time to think about how to respond to whatever I do’. (In TRIZ terms, we might think of this situation as a Controllability-versus-Speed contradiction – you might like to look up what the Contradiction Matrix says about that to see how the doosra fits what TRIZ would have recommended!)

Switch/Shift/Surprise/Step-change (I’m not sure which word I like best yet) – having identified the obstacle, the next job is to solve it. Coming up with solutions means making some kind of a step-change to relative to the usual way of doing things. In TRIZ terms this step-change is going to come from one or a combination of the 40 Inventive Principles. Each one represents, in effect, a provocation that says to the problem solver, ‘how would segmenting the problem help you to solve it?’ or, ‘how would ‘doing it the other way around’ help you to solve it?’ With the doosra, the clear switch/step-change involves getting the ball to bounce in the opposite direction to the one the batsman expects. Whether we use the 40 Principles or any other ideation strategy, the job in this ‘S’ stage of the DOOSRA innovation process is to generate our solution ‘clues’ and ideas…

Resources – once we have our provocation-originated solution clues, the next job is to look at what resources we are able to bring to bear to help turn those clues in to a practical reality. Resources are things or sources of energy or sources of information in or around the current system that are not being used to their maximum potential. For Saqlain Mushtaq it was working out how to hold the ball in a different way, and how to apply the necessary switch of the wrist at the right moment during the rotation of his arm that would still allow him to keep his arm – per the rules of cricket – straight.

Action – it’s all well and good to have a good solution to a problem, but we can probably well imagine that Saqlain Mushtaq didn’t just magically dream up the perfect doosra during a live match. Rather, he spent long, hard hours in the nets experimenting and no doubt failing before he got his technique to a point where he thought it was good enough to try in a competitive game. Those ‘hard yards’ of failing, re-thinking, failing again, trying again, failing again, wiping away the tears, and relentlessly persevering through the blood and guts, and stress and frustration is what we might think of as the Action stage of the innovation process. Thomas Edison famously said that innovation was 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration. The Action stage is where all the perspiration is going to happen. Most innovation attempts fail here. They fail because many people fall into the mis-apprehension that once they have a good idea, that’s the hard bit over with. ‘Action’ means recognising that the hard work has barely started yet.

So there’s DOOSRA innovation. The only thing left to think about, just like Saqlain Mushtaq, is that real success comes not just from innovating once, but from going back and doing it again. Doosra becomes teesra (‘the third one’). Which, one day soon, might just turn out to give us a whole new innovation acronym…