One of the reasons I left the academic world was that I got sick of having what I thought were really insightful papers rejected because they didn’t contain enough rigour. Now because I look after a team of 20 much-smarter-than-me full-time researchers, this sort of comment used to catch in my craw a little bit. They’d done rigour until they bled; my job was to try and turn their hard work into something interesting. Which in my mind meant getting through to the other side of the complexity, to something that was both simple and meaningful. So, whenever I questioned what sort of rigour referees were looking for what it seemed to always come down to was mathematical formulae. The basic correlating relationship is this: the higher the number of convoluted mathematical derivations per page, the higher the likelihood of acceptance, and the smaller the likely readership.

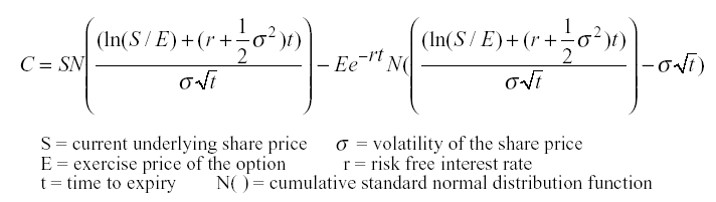

I used to be a mathematician, and I can still get excited by a good piece of mathematical genius, but when I saw this equation for the first time, I knew I had to begin weaning myself off the algebra and back into the real world.

This is a formulae that delivered a Nobel prize in Economics to the pair that came up with it a couple of decades ago.

Today we know that it is meaningless crap. Nay, it’s worse than that, it’s dangerous meaningless crap. But because it came with a ‘Nobel’ pedigree, and it made for some really great computer models, it in effect generated its own little industry. It’s the very definition of crackpot rigour. i.e., the unquestioning acceptance that sophisticated mathematical models must automatically be correct.

The clue to the problem here is in the word ‘economics’. Increasingly a terrific warning sign that what you’re about to hear next is also meaningless crap. Economists serve as the veritable archetypes of crackpot rigour. I blame the numbers. Economists live numbers and love numbers. Their problem is that the large vast majority of the important numbers in life are, to quote W Edwards Deming one more time, ‘unknown and unknowable’.

Any idiot, for example, can look at the patent databases of the world and count the number of times that a patent was cited by other patents. But the crackpot-rigour idiot (CRI) wants to turn it into this:

A really beautiful picture, that – best of all for the CRI – clients appear willing to spend lots of money for. After all, it looks really scientific. Really plausible. Just think of all the data and all the intricate mathematical analysis that went into its creation.

Because these days my aforementioned researchers spend a lot of their time analysiing patents, this is the sort of picture guaranteed to make my blood boil. I know, I know, I should jump on the bandwagon and make some pretty pictures of my own, but sadly for me, I have the naïve desire to sleep at night without the feeling that I’ve been wasting people’s time and money.

The problem is this. When you really get down to it, and try and work out what’s meaningful and what’s relevant, if we want to really study what’s happening in the world’s store of intellectual property, the number of citations a patent receives has practically nothing of value to tell us. All it means is this is how many other inventors referred to this one. It doesn’t matter whether they might have referred to it as an example of a really bad invention that their’s is an improvement on, or whether they referred to it because it was one of their own earlier inventions that they’ve subsequently improved upon, the key thing is that the cited patent has now been improved upon, thus making the earlier patent somewhat redundant.

Add to that rather inconvenient reality the fact that citations can only ever happen after the earlier patent has been made public, and you’ve now just made a beautiful picture that’s also about two years out of date.

And if that’s not bad enough, some ornery new inventor might just come along tomorrow morning with a new invention (uncited by anyone, anywhere) that just made your invention completely irrelevant.

There’s the only meaningful stuff: how much is my patent worth? (easy one: probably zero) How likely is it that someone will come along tomorrow and design around it? Who could I license it to? How could I use it to block my competitors. All the stuff, in other words, that has nothing to do with mathematics at all. Much as the economists might deny it, there is no mathematical model that will ever be able to take due account of the testosterone-driven foibles of the business strategist. Well, unless it’s our PanSensics tools, of course, but that’s another story. Albeit one that also doesn’t produce pictures that are nearly as pretty as the crackpot rigour ones.

Big Data Analytics apologists will argue that meaning comes from the meta-data. i.e. we need to step far enough above the mathematical detail to see the bigger picture. The meta-data doesn’t lie they will argue. Well, there certainly no rule that says it will, but it probably does. If your starting assumptions were garbage (i.e. numerical), when you integrate it all together into your pretty picture, all you’ve really done is created meta-garbage.