First up, everything is complex. The only thing in doubt is how far up or down the hierarchy of turtles do we have to travel before we realise we don’t really understand what’s going on any more.

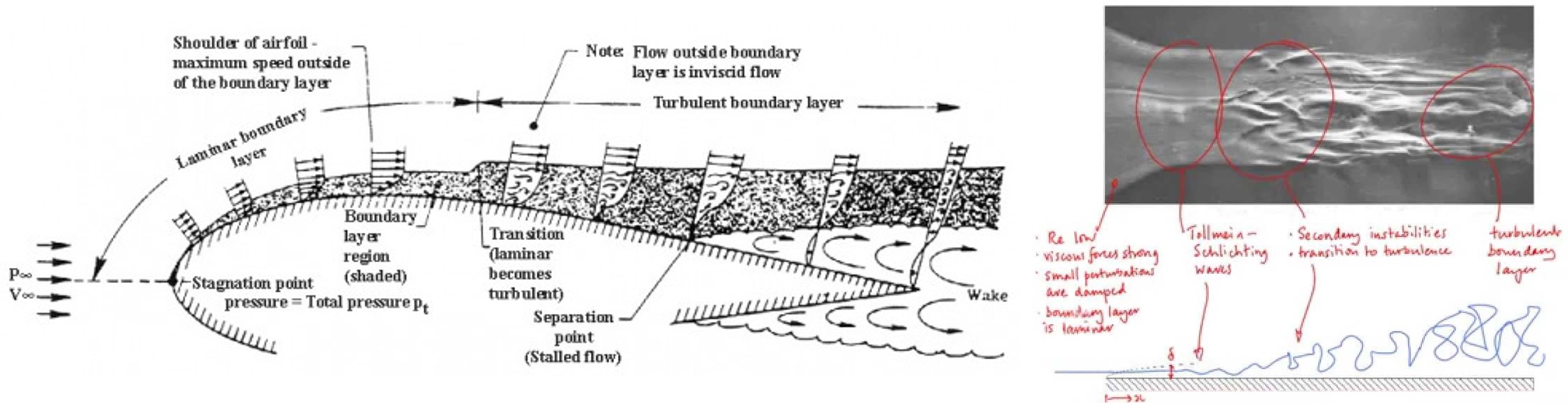

I used to design jet engines. Jet engines are complex. Not that we liked to admit it because it tends to make passengers and crew nervous. I used to design compressors. They’re complex too, and we didn’t like to admit that to ourselves either. Much of the complexity occurs when we get down to the molecular level and start to think about the behaviour of the air molecules flowing over the compressor blades, especially in the boundary layer region. Especially when the layer is turbulent. With a big enough computer program you can sort of model what the air molecules are doing, but you’re not entirely sure. So what you do is do the best you can, then build in a safety margin. When every designer of every component in the engine does the same and we bolt all the components together (a jet engine is often described as a ‘quarter of a million components flying in close formation’), we then add another safety margin for good measure. Then you can say to a pilot, provided you keep your aircraft within this operating envelope, we guarantee everything will be all right. Flying the aircraft will still be complicated, but it will be guaranteed safe.

A similar thing happens at the other end of the turtle scale thinking about the people tasked with maintaining the engines. The moment we add humans to the picture, we know we’re in complex territory again. Humans are not error-free. Stuff happens outside work that affects what happens in work. The crew just had an argument about overtime with the boss. Everyone’s in a bad mood. But that doesn’t affect the safety of the aircraft because everything’s been designed so that the complexity is confined within a set of very clear protocols. If anything goes wrong the system won’t let you proceed. If any two things go wrong, ditto. And so on.

(By the way things aren’t this sophisticated in other industries. If the driver of a car does something stupid, the safety systems will usually save the day. Most car accidents occur when two or more people aren’t driving with due care and attention – driver A is sending a sneaky text and accidentally drifts out of their lane at the same time Driver B is shouting at the kids in the back of the car and isn’t really looking when they pull back into the same lane after overtaking another car.)

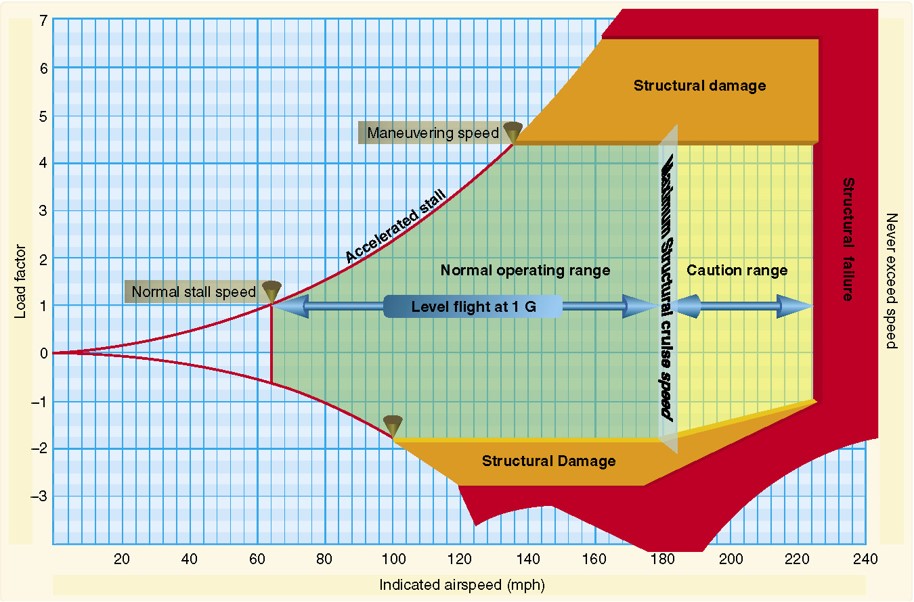

Meanwhile, back in the far safer air, so long as pilots stay within the allowed operating envelope and everything will be okay. Complicated, but okay. Go outside the limits, and now you’re back in the hands of complexity. Sometimes circumstances put you in such situations. If you’re a fighter pilot in a dogfight for example. Now you can easily find yourself outside the controlled ‘complicated’ envelope and into a world of ‘not quite sure’. Keep veering into this territory and fairly swiftly ‘complex’ turns ‘chaotic’. Reach the chaotic stage and you’re really in trouble. While in complex, at least you know know the likely dangers because part of the job of designing and testing the aircraft has been to go and fly in those parts of the envelope to see what happens.

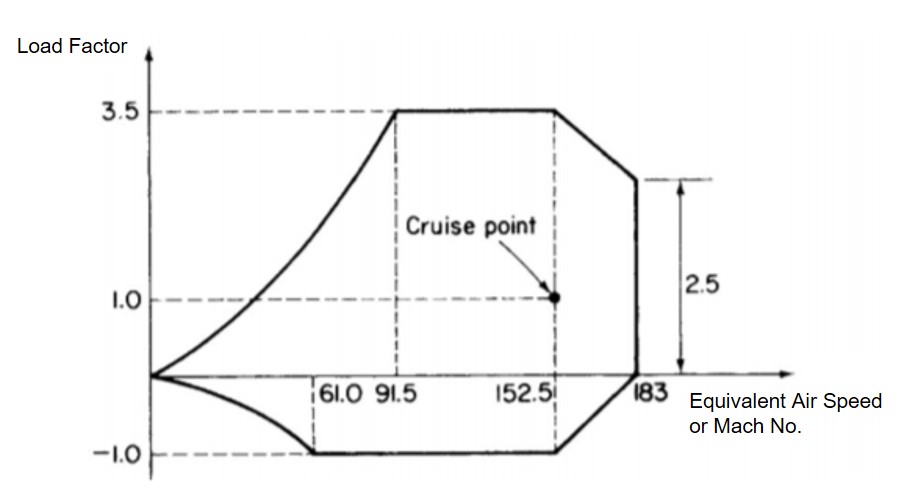

The next important feature are the labels on the axes. They’ve been ‘non-dimensionalised’. Which means that the numbers are relativised to the real world around the aircraft. If the environment changes, the aircraft’s position in the envelope changes. Pilots have to live in the real world, and that’s only possible when we know where we are relative to our surroundings.

There’s another, final, feature of the flight envelope story that is important, and that’s the ‘design point’ or ‘cruise point’. This is the point in the flight envelope to which everything has been optimised. It’s the point where the aircraft will spend most of its time. It’s the point where the plane pretty much flies itself. At the cruise point, not only has the complexity been absorbed, so has the complication. The plane is in ‘obvious’ mode.

Every enterprise seeks to find these ‘obvious’ operating conditions. The primary thrust of things like Six Sigma is to minimise deviation from an optimum ‘design point’. Deviation in the Six Sigma sense is bad. Deviation brings complication. And, worse still, if we deviate too far, we can find ourselves out-of-control in a complex environment. The main difference between aircraft design and most enterprises on the planet is that in an aircraft you have to know where the obvious, complicated, complex and chaotic boundaries are, and not only that, you also have to know where you are relative to the environment that you’re operating in. When I try and quiz enterprise leaders on these issues the inevitable response is they have no idea what I’m talking about. They have no idea what their envelope is. And even less idea of how to non-dimensionalise the envelope to take account of the external environment. If pilots don’t understand these things, they don’t survive for very long. The same applies to business. If managers have no idea where they are, the likelihood of appropriately managing the business is small, and, as the environment gets increasingly turbulent, becomes ever smaller. Especially since, irrespective of our desire to make everything obvious, the reality is turtles-all-the-way complex.