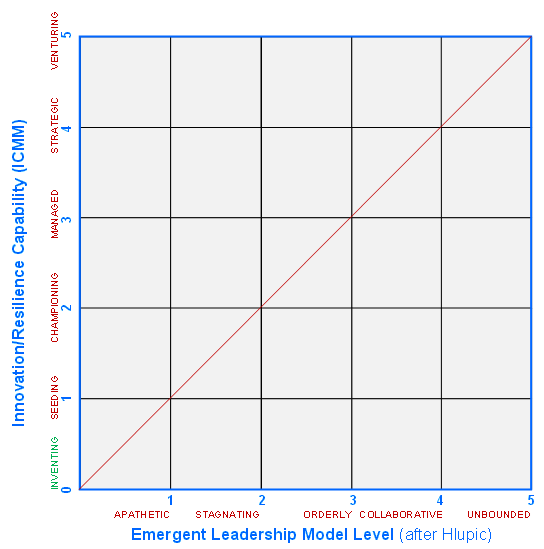

As I was reading Vlatka Hlupic’s book, Humane Capital (see Best-of-the-Month review in the current issue of the SI ezine) I was struck by the apparent similarities between her Emergent Leadership Model (ELM) and our Innovation Capability Maturity Model (ICMM). Both contain five stages, and both recognise that each stage is a step-change jump from the previous stage. Both, too, recognise that the jump from Level 3 to Level 4 is all about making the leap from managing an organisation as a Complicated entity to one that is Complex. From an innovation perspective, Level 3 is called ‘Managed’. In Hlupic’s world it is called Orderly, and in effect describes the leadership modus operandi for to achieve a ‘well-run’ command-and-control hierarchy. The sort of management structure first devised by F.W. Taylor. And the sort still taught in the large majority of MBA programmes around the world today. A big thrust of the Human Capital book is that the shift from Level 3 to Level 4 in effect is about abandoning Taylorism and starting to treat employees as intrinsically motivated, wanting to make a difference, meaning-seeking human beings. And if that sounds kind of scary, that’s kind of the point. Level 4 is a sea-change different to Level 3. Fortunately, Hlupic’s book is written for Orderly Level 3 managers. Primarily by making an evidence-based, Taylor-compatible argument that evolving to Level 4 is good for the business, customers and everyone else in a value ecosystem.

In the Innovation Capability Maturity Model, Level 4 in effect needs a leadership model that matches Level 4 on Hlupic’s scale.

Importantly, that is not the same as saying that an enterprise that achieves Level 4 on the Emergent Leadership scale will also have achieved Level 4 on the ICMM scale. Indeed, the majority of Level 4 companies found in Hlupic’s analysis are nowhere that Level when it comes to innovation. A Level 4 Emergent Leadership Capability, in other words, is necessary but far from sufficient to achieve a Level 4 Innovation Capability Maturity.

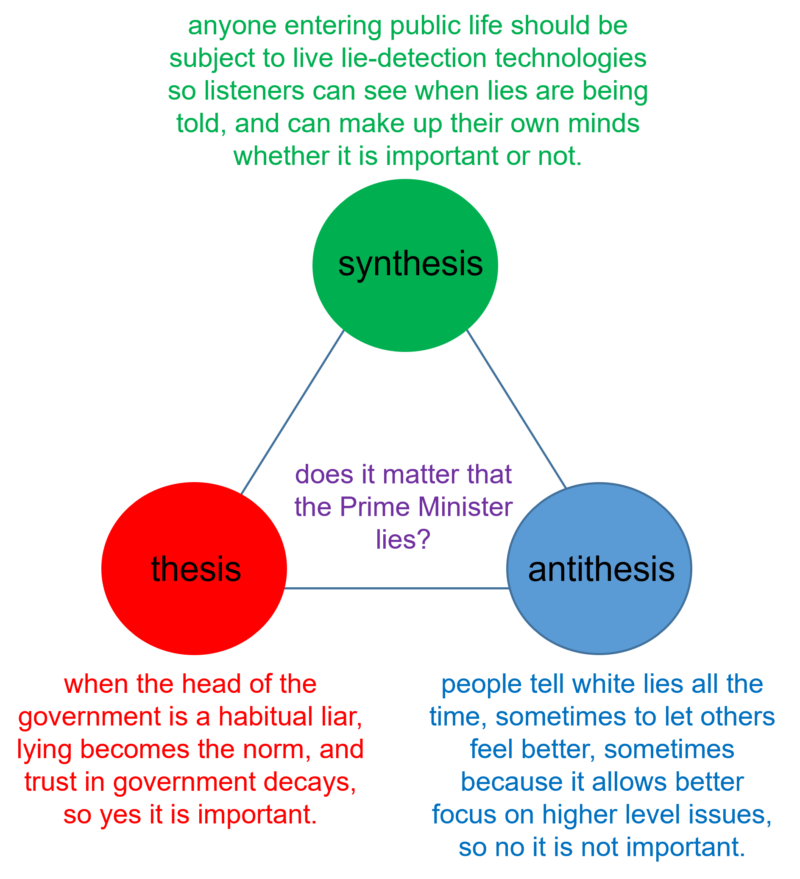

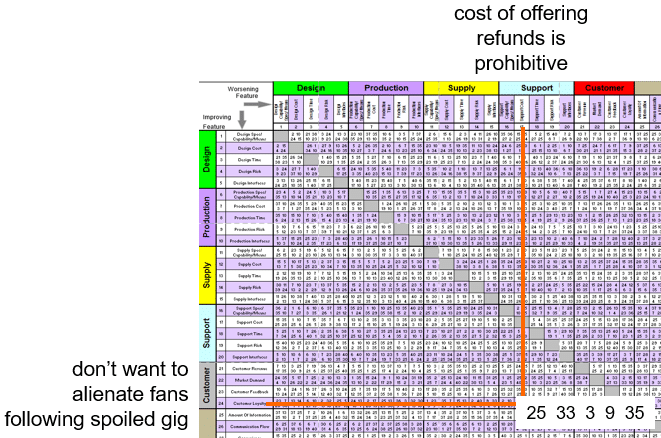

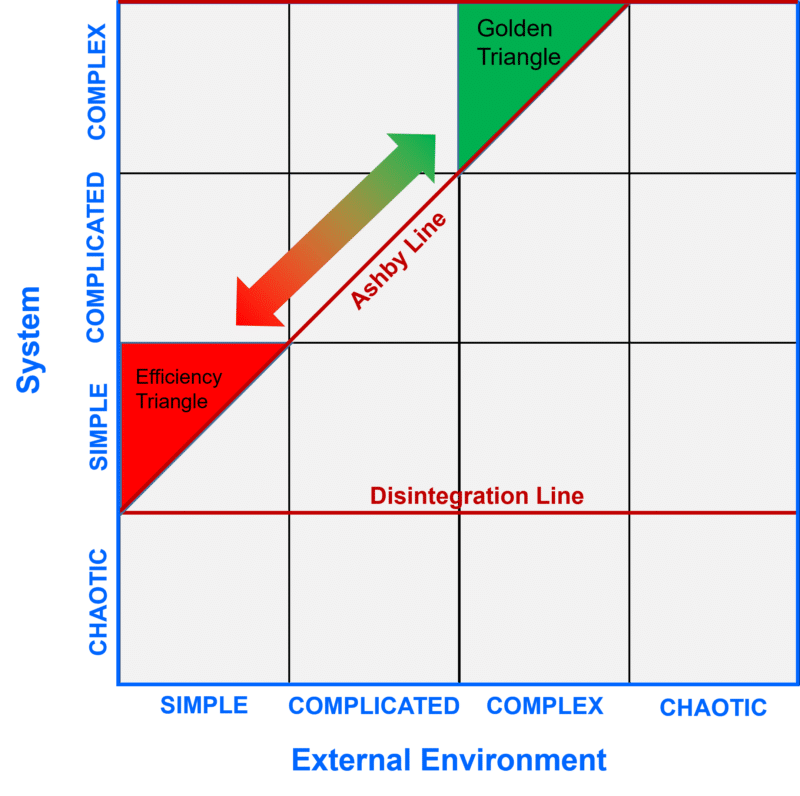

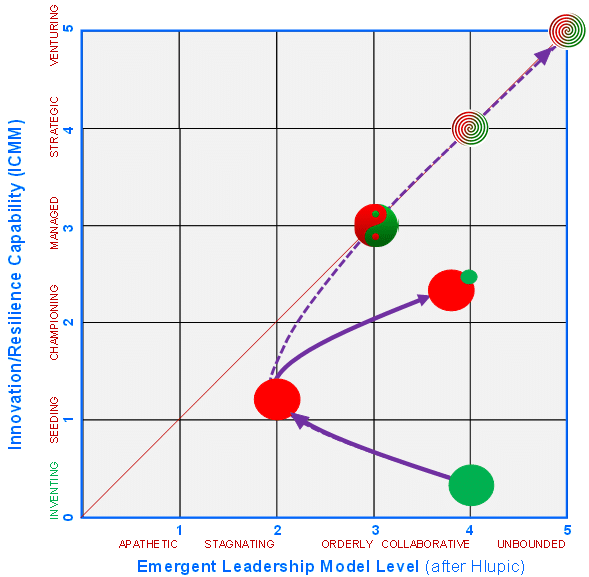

In many ways, but particularly when organisations operate at Level 3 or below on either scale, there is very little correlation between Emergent Leadership and ICMM. To the point in fact, where it is probably prudent to consider the two models as orthogonal axes on an overall organisational capability map. A map that might look something like this:

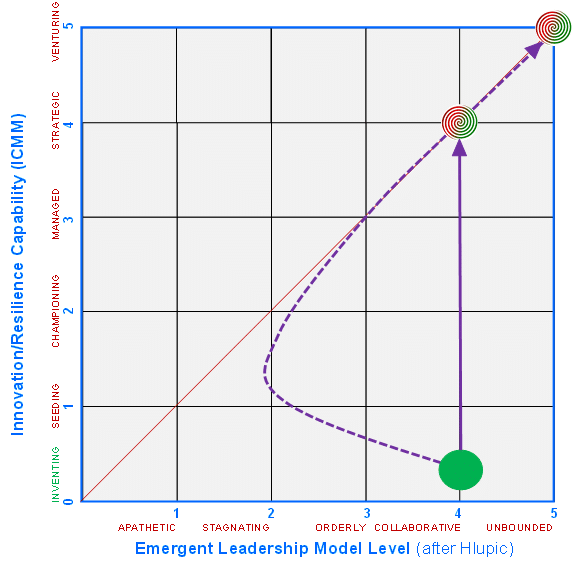

One of the most striking differences between the two models begins with start-up enterprises. From an Innovation Capability perspective, any start-up that is in business to offer the market something new is in effect operating at ICMM Level 0. The Hero’s (Start-Up) Journey book is in effect all about what these start-ups need to do to survive long enough to reach the revenue/profit making goals that help characterise a Level 1 enterprise. It is important to note that there is no Level 0 in the Emergent Leadership Model (ELM). Rather, the start-up leaders Hlupic interviews for her book more often than not already exhibit ‘Collaborative’ Emergent Leadership Level 4 Capability. In that small, cash-hungry, fighting-their-way- through-the-jungle start-ups pretty much by definition need leaders that are able to embrace the complexity and chaos that surrounds (and frequently engulfs) them. They tend to be flexible, agile teams where everyone is expected to get stuck in to whatever needs to be done to keep the boat afloat.

This ICMM/ELM start-up mismatch reveals something of a quandary. Why, if enterprises start as Collaborative Level 4’s, does their survival past the start-up stage cause their Leadership Capability to fall? Or why, expressing things in ICMM terms, is it that once organisations have successfully built a stable, efficient, Operational-Excellence capability do they end up with dysfunctional, Taylorised management hierarchies? Or, to express the quandary in more blunt terms, why did Hlupic need to write her book?

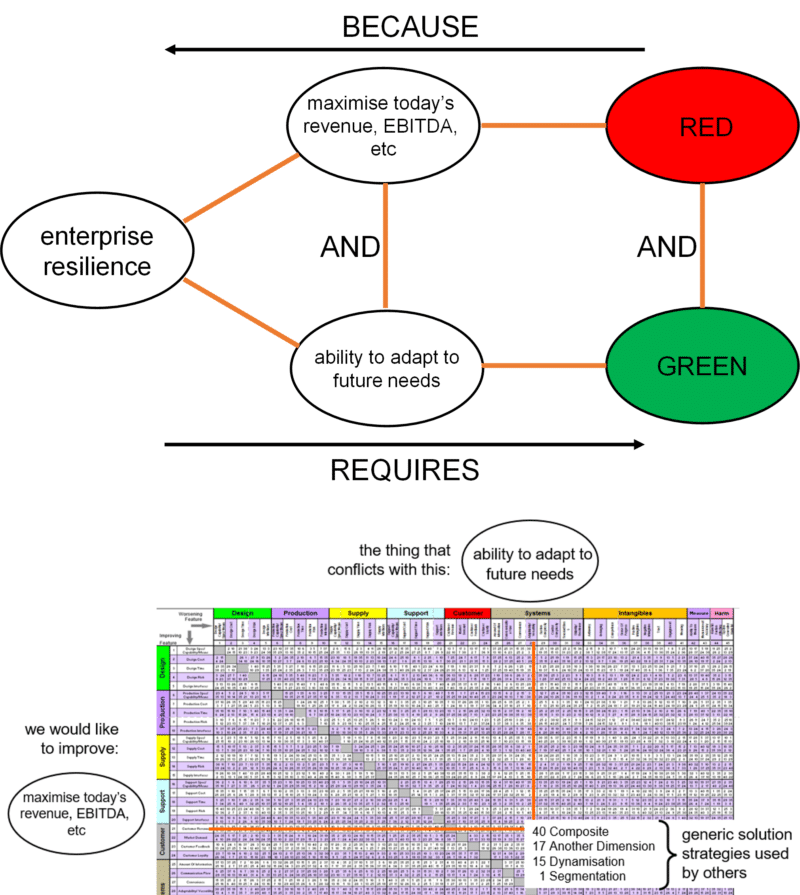

In graphical terms, the problem looks something like this:

The answer to the puzzle, I think, starts with investors. A community of people that tend to look at the apparently ramshackle nature of leadership in the start-ups they’re thinking about investing in and feel a need to make their investment dependent on the recruitment of ‘professional’ managers. A COO. A CFO. Numbers people. Red World people. People with a track record of managing businesses. People – and here comes the second answer to the puzzle – that have a Taylor-merit-badge MBA. People that, not coincidentally, look the same as the investors.

Hlupic’s book is in effect all about how to re-educate those Red World professionals to understand that EQ is massively more important than IQ. And leads to more successful enterprises.

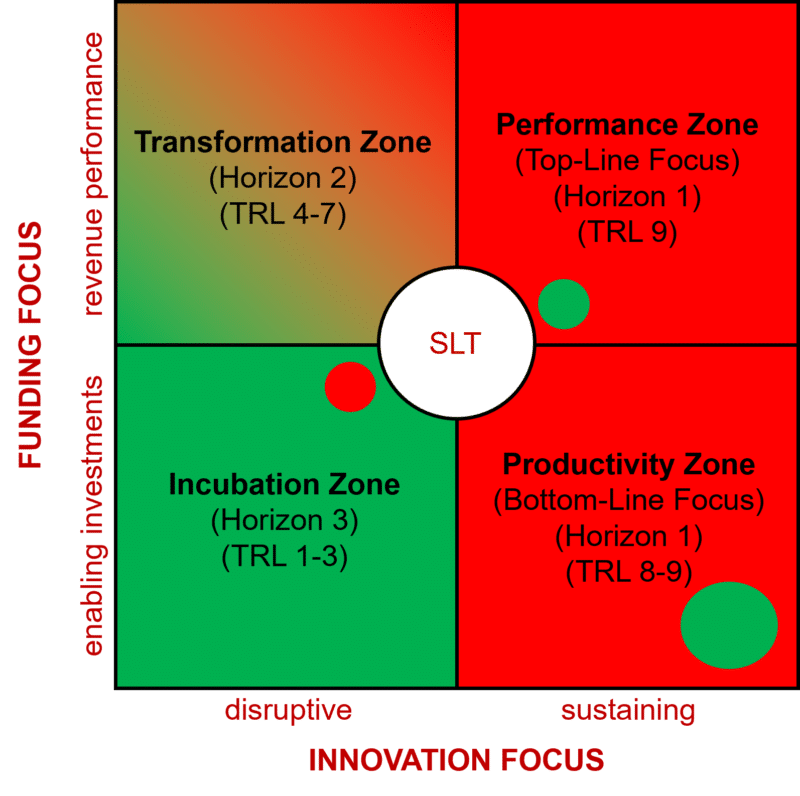

While applauding that ambition, my work is in Innovation World – also known as, noting the added word in the ICMM axis of the above graphs, Resilience World. Given the choice of working with an ICMM Level 2 (I pretty much refuse to work with Level 1 organisations these days) with ELM Level 1, 2 or 3 or one with ICMM Level 2 and ELM Level 4, I will take the latter any day of the week.

That said, sweeping aside the minor problems of an out-of-touch academia and naïve (ELM Level 3 at best) investors for a second, the new ELM/ICMM framework makes me wonder whether the world of work would be a whole lot more productive, profitable, meaningful and fun if we stopped corrupting Collaborative start-up leadership teams and designed a more direct route to Level 4?

As with all things, it’s usual for things to get worse before they get better, but it’s not compulsory.