(These words formed the initial draft of the first chapter of the GenZ book we contributed to earlier this year – http://www.happen.com/48-hr-book/download-the-48hr-book. Page number limits ultimately meant it didn’t fit… so it’s now here instead.)

“At bottom every man knows well enough that he is a unique being, only once on this earth; and by no extraordinary chance will such a marvellously picturesque piece of diversity in unity as he is, ever be put together a second time.”

Friedrich Nietzsche

or

“There are only 40 people in the world, and five of them are hamburgers.”

Don Van Vliet (Captain Beefheart)

How and why does each of us grow up to be a unique individual? Are people’s characters fixed early in life or can they change as adults? How will our collective characters affect the future? What will the stock market be doing in two years’ time? In five? In ten? What products and services will people be buying? What won’t they be buying any more? How can parents best prepare their children for the future? What should they be doing for them? What should they not be doing?

We, all of us, like to know what’s around the corner. The human brain is, in effect, a prediction machine. Albeit one that only tends to look forward a short distance before our powers of deduction fail us. Some purport to do the job better than others. Some even write books about what the future will look like. Sadly, some of the things that emerge from these predictions tend to come back and haunt the authors. Heavier than air machines will never fly, there’s a global market for about a dozen computers, no-one will need more than 64K of computer memory. The inability of even the experts closest to their subject to get it right is the stuff of gleeful legend. To the extent that, if anyone approaches us claiming to be able to see into the future, our best course of action is probably to cross the road and get as far away from those people as possible.

So why are we now about to do the same thing?

Well, first up, at the very least, we’re strong believers that planning for the future is important. Even if the plan that emerges ends up with a relatively short shelf-life. Secondly, because we’ve been working at this problem for the last 20 years now, we think we’ve learned a few things about the way things evolve that allow us to do a better job of mapping the future than anyone else out there. Not that that is necessarily saying very much. If the finest minds on the planet can’t do it, what chance have we got?

Actually quite a big one. It’s a chance that starts from an idea we all carry to some extent: just because we can’t predict everything about the future, doesn’t mean that we can’t predict anything. For some reason, the world seems to have developed a depressingly black-and-white view of futurology, when in reality it’s a million different shades of grey.

Some aspects of the future are nigh on guaranteed. The number of babies born into the world this year, for example, gives us a pretty good indication of how many primary school-age infants we will have in five year’s time. And a strong set of clues about the extent of government services, the number of doctors and nurses and the amount of food and water we will need for the next 80. But somehow our governments seem to be surprised when these kinds of things pan out the way they do. We might think of them as ‘inevitable surprises’.

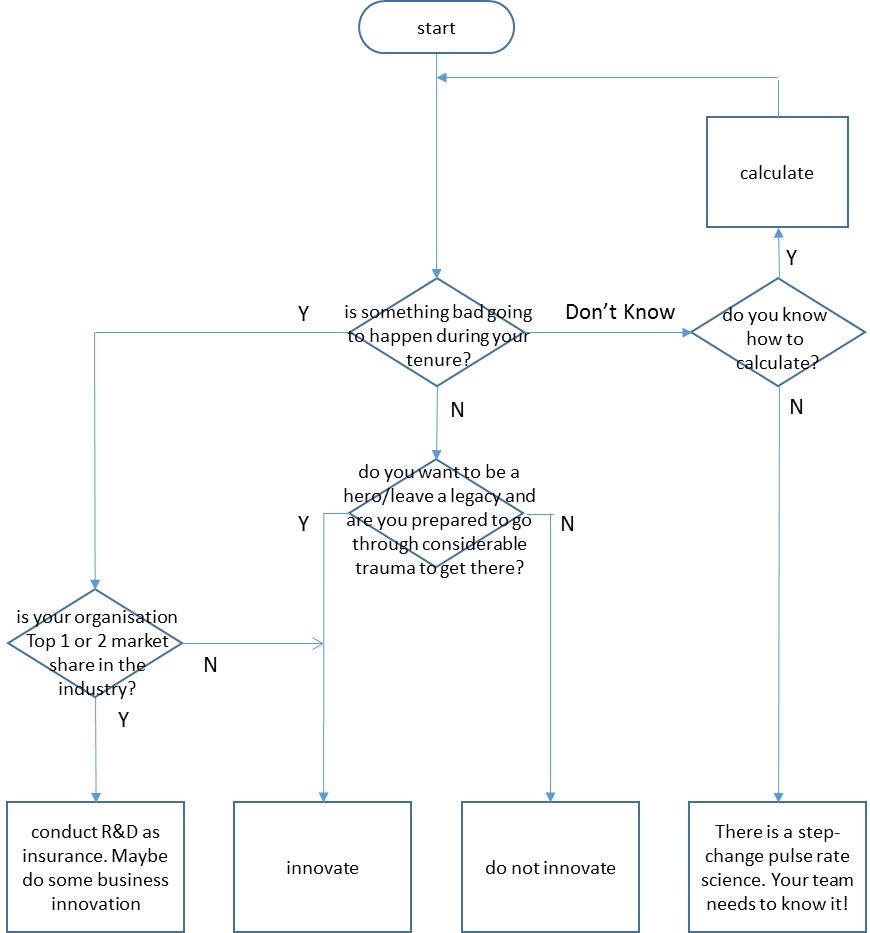

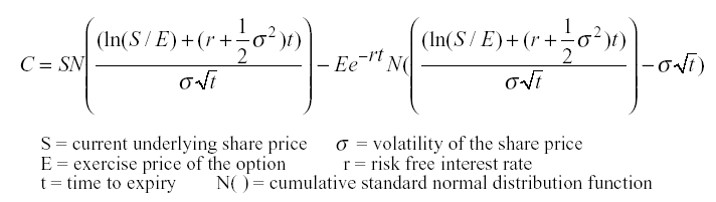

Beyond these ‘inevitable’ things then come a bunch of things that are to some degree calculable. It’s difficult to know with any kind of certainty, staying with the primary school theme, precisely how many parents will decide to home-school their precious offspring, but that’s not the same thing at all as being able to make some kind of meaningful calculation based on past patterns of behaviour.

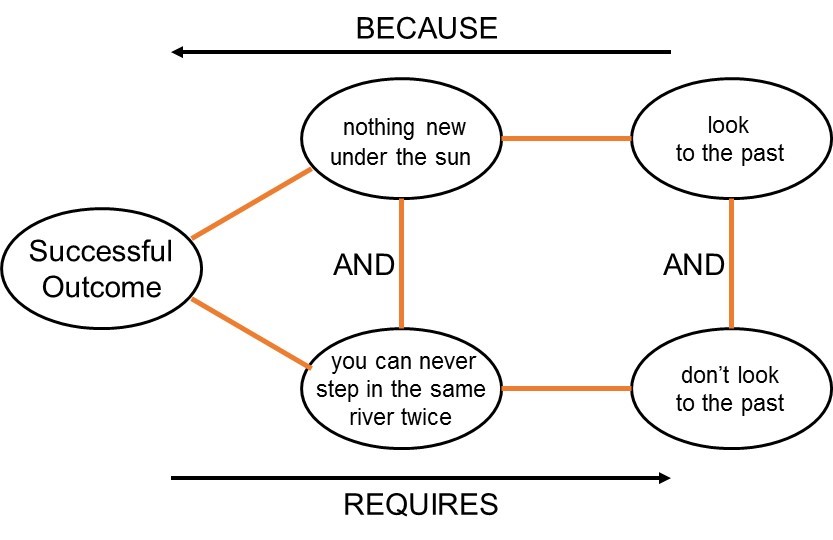

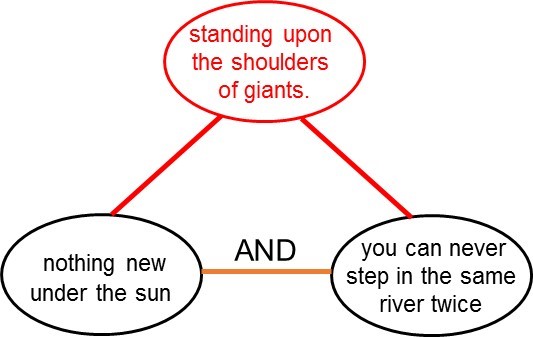

And that’s where the methodology underpinning this book comes in to play. There are a host of patterns that we can look back through time and see playing out time and time again. We can also see that there are times when they don’t. Traditionally, that’s when these kinds of prediction stories come to a sticky end. The real trick is knowing why sometimes patterns repeat and sometimes they don’t. That’s the underpinning ‘DNA’ of our research, and the heart of what we’ll reveal about Orkids in this book.

Look back through history – whether it be decades or centuries – and one of the things you can observe are a host of oscillatory patterns. Between left and right wing governments for example. Or between economic boom and bust. Centralisation and decentralisation. Individual freedom and collective responsibility. Gender difference. Or between baby-booms and baby busts. These oscillations keep occurring so long as no-one tackles the underpinning conflicts and contradictions that create them. Example. The NHS has recently undergone another traumatic re-organisation and shift of power away from ‘managers’ and back to ‘clinicians’. In addition to being traumatic for those involved, it’s a shift that has already been massively expensive in both cash and patient care (or lack thereof) terms. Crucially, too, all it has done is shifted the same basic problem from one side of the trade-off back to the other. And because that’s all that’s happened, we can make a fairly safe prediction that at some point in the not too distant future, the pendulum will swing back in the other direction.

Here’s another one. If you’re a parent with young children right now you’re very likely to have them on a pretty short leash. It’s a good idea to know precisely where they are and what they’re doing at any moment in time. If only because all the stories you hear in the media tell you this is what parents are supposed to do. Go back 40 years though and parental attitudes were very different. Some of the members of this team of authors were practically feral when they were kids. If you’d’ve asked those parents where are your kids, they would very likely have shrugged their shoulders and speculated, ‘out playing?’ Which is not to say that those parents loved their kids any less, but simply that what we’re seeing is two ends of the same pendulum. The fundamental contradiction between looking after our children while simultaneously providing them with the skills they need to, later, survive as adults in the big wide world still hasn’t been solved. And probably won’t be for a good long while yet. Which in turn means we can make a fairly safe prediction that parental-leashes will start to lengthen again in the future. The only uncertainty here is when?

And, we propose, even that answer is mappable with a fair degree of precision. A precision based on a (painfully gathered) understanding that the ‘pulse rate’ of many things in society is dictated by a generational transfer of behaviours from one generation of parents to the next generation of offspring. The way you were raised by your parents, in other words, will later on affect the manner in which they will raise their own.

That’s the first strand of the basic bottom-up ‘DNA’ of the model we use in this book. The way in which you the individual reader reading this paragraph were raised by your actual parents will influence the way you are or will raise your own offspring. Like your parents, you too are unique. Just like everyone else in your group of friends and peers. And that’s the next strand of the societal DNA… it’s difficult for any of us to stand out too far from those peers. In no small part because the media keeps reminding us that it can be a pretty lonely place standing too far away from the crowd. Society, in other words, has a way of putting in place correction mechanisms that mean we all tend towards a self-organising average.

The third and final strand of DNA holding this book together is an understanding of complex systems, and specifically the idea of emergent behaviour. What this translates to in practical terms is that there are a whole bunch of random events that occur in the world, some of which will quickly fade into insignificance while others will come to change all of our behaviours. ‘Shit happens’ was the oft used phrase of the 80s, but society’s reaction to whatever shit it might be is very strongly conditioned. And, moreover, is most often conditioned by our generational cohorts. Of which, contrary to the suggestion of Captain Beefheart at the start of this chapter, it turns out thus far that there are only four. Only one of which is a hamburger.

Children, to move on swiftly before we get into an argument we don’t want to start, have been the subject of kidnappings since humans evolved to live in tribes. Thousands of children a year are kidnapped. But if you look back through the last hundred years only two seem to have stuck in the collective memory. Today, it doesn’t matter where you are on the planet, people know the name Madeleine McCann, and the fact that poor little Maddie still hasn’t been found. The other name is Charles Lindbergh Jr. Okay, you may not have heard of him, but we all still remember his father, the first man to fly solo across the Atlantic. Back in 1932, though, it was the kidnapping of Lindbergh’s son that had the global media in the same Maddie-frenzy we see today. The fact that Lindbergh Jr and Madeleine McCann are precisely four generations apart is, we propose, quite significant. Out of all the thousands of kidnappings that take place, these are the ones that hit a moment in time when the world was at its most receptive to media messages reminding parents that the world is a dangerous place, and you need to keep your eyes on your precious little ones at all times.

Here’s another one. September 11, 2001. A day when, no matter where you lived, the world changed. Its four generation ago equivalent was the Wall Street Crash of 1929. Again, events can happen at random, but society’s reactions are strongly conditioned by generational effects. Both 9/11 and the Crash – two quite different (random) events on one level – ended up having the same basic trigger effect on societal patterns. 9/11, indeed, proves to be particularly significant as far as this book is concerned. Many things changed ‘post 9/11’, but one in particular was the behaviour of parents. A baby born into this new world was a baby born to parents who now had tangible evidence that the world was a dangerous place. A dangerous place that meant a significant shift in parenting behaviour towards making sure our kids were safe at all times. 9/11 turned out to be a significant generational turning point. And, in a classic case of ‘you reap what you sow’, we’re just about to start experiencing some of the consequences of that shift in parenting behaviour. The oldest of those post 9/11 babies hit their teens this year. And as such – no matter what their suffocating parents might think about it – they begin to start making their own way in life. Making their own decisions and doing what they want to do rather than what their parents might desire. And that’s precisely why we’re publishing this book now. Sure, we’ve been researching this subject for the last 20 years, and sure too that research will continue for the foreseeable future, but the reason for embarking on a ’48 hour’ book writing blitzkrieg is that moments like this only occur once every four generations.

Now, we don’t know about you, but if anyone comes to us trying to tell us that our Society emerges from a bunch of patterns that somehow keep repeating every four generations, no matter how hard they might argue their case, we’re still unlikely to believe them. That’s why our entire research rationale for the last 14 years has been to try and dis-prove the model. The fact that – no matter where or when in the world we look – we’ve as yet failed to do that means that we’re happy to present some of the things that come out of applying the model. One might say were at the stage of believing ‘all theories are wrong, but some are useful’. We know ours is at the ‘useful’ stage because we’ve been working with clients from literally all walks of society in just about every region of the world helping them to design and deliver what we can now rightly claim to be billions of dollars of new revenue and hundreds of millions of dollars of bottom line savings. The model, in other words, has been verified and validated in the only meaningful manner possible: did it tell us something that allowed us to create deliver a successful step-change to our clients.

It’s not the job of this book to describe all of the underpinning research to readers. Any that want to delve deeper might like to explore one of our TrenDNA or GenerationDNA texts. The job of the book is rather to reveal clues and insights into a specific emerging generation of what we’ve come to think of as Orkids. In the next chapter we’ll share enough of the model to show readers why and how this generation will be classified as ‘Artists’ and what this means for the next twenty years of their evolution. After that the focus shifts to the construction of a description of likely characteristics of the Orkids and, then, to some of the likely implications, threats and opportunities for parents, teachers, government officials, product designers and marketers.

We realise, almost finally, that there are sceptics out there (hello, Generation X readers!) who wouldn’t believe this stuff even if they’d lived with us for the last 14 years. To them we say, it’s great that they bring that scepticism to bear on the words to come in the rest of the book. We’re not asking anyone to ‘believe’ every word of what we write. What we are asking is that, at the very least, you use our thoughts as provocations, stimulus and some perhaps far-fetched sounding clues to base some of your future scenarios around. Insight, we firmly believe, comes from contradiction. It is, therefore, the places where you find yourself disagreeing most vehemently with our projections, where the greatest innovation opportunities exist.

Finally, by way of a health warning for those carrying an upbeat, glass-half-full view of the world (hello, Generation Y readers!), a lot of what we’re suggesting is likely to occur in the next twenty years isn’t good news. Not for our Orkids or the world they are about to begin exploring for themselves. The next ten years, our model suggests, is likely to see the calm-to-crisis pendulum swing even further into the direction of ‘crisis’. Some people won’t like to read these words. We write them for two reasons. Firstly, in any crisis period there are always winners, and you’re more likely to be one of them if you have your eyes open and know where and how to look for the inevitable opportunities. Second, and more important, knowing that complex systems are emergent, we also know that the crisis isn’t inevitable. Or, if we’re already too late to prevent it from happening, at the very least, we might – collectively – be able to change sufficient small things to create a momentum that mitigates the worst of it. Our Orkids are depending on us.